We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Madame Norman-Neruda and a short history of women violinists, Part III

June 10, 2010, 10:35 AM ·

This is the concluding part of a three-part essay.

Click here for Part I

Click here for Part II

Thanks to everyone who has given such terrific feedback. I'm hoping to continue my studies of the great female violinists so watch out for future blogs.

In 1885 Ludwig Norman died, leaving his estranged wife a widow. Three years later Wilma married Charles Halle, who had been widowed himself in 1866. Halle was a formidable pianist (he was the first pianist to play a complete Beethoven sonata cycle in England) and conductor (he was the founder and first conductor of the famous Halle Orchestra in Manchester; it is now the fourth oldest orchestra in the world). Wilma and Charles’s paths had crossed for the first time in May of 1849 when the Neruda children had performed at one of Charles Halle’s Gentleman’s Society concerts; Wilma had been a ten-year-old prodigy and Charles a thirty-year-old conductor. Ever since that first performance they had kept in touch and had often performed with one another. A few months after they were married, Charles was knighted for his musical services to the Empire. Wilma accordingly became Lady Halle, the name she is most often remembered by today. Together they gave a wide variety of concerts, ranging from chamber music to concerto work. A few years after their marriage, Charles established the Royal Manchester College of Music after decades of dreaming about the project. Although it is unclear if Wilma was on the faculty, her pianist sister Olga was invited to join the staff. Olga worked in Manchester, teaching and performing, until her retirement in 1908.

Charles Halle, Wilma's second husband and lifelong musical partner

In 1890, Wilma and Charles embarked on a tour of Australia, then widely considered by the English to be a wild frontier land. In 1895 they toured South Africa. In his memoirs Charles Halle recalled one concert where he and Wilma performed the Kreutzer sonata by Beethoven at a municipal concert. There were to be a few numbers both before and after Charles and Wilma took the stage. After they had finished and acknowledged the thunderous applause, a member of the audience came forward and suggested that the rest of the performances be canceled, saying that the Halles had played so perfectly there was no point in continuing. The rest of the audience quickly acquiesced and the concert was finished. Later, a thousand South African natives assembled to dance war dances and sing in Wilma’s honor.

Tragically, a few weeks after they returned from their monumental South African tour, Charles Halle died suddenly after an illness of only a few hours. Three years later, Wilma’s son, Ludwig Norman-Neruda, now a famous mountain-climber, died after a fall on a hike in the Alps. Never one to avoid work, even in times of personal turmoil, Wilma embarked on an ambitious tour of the United States and Canada the next year. She ascended each concert podium dressed entirely in black in memory of her son (and perhaps her husband, too).

A Toronto reviewer raved:

The programme she gave last night was an old-fashioned one, with the rarely seen names of Tartini and Spohr upon it; men who were at once brilliant composers, and, the former in the 18th century, the latter in the 19th, exponents of the classic school of violin playing. Lady Halle, in these days of the strenuous emotionalists, stands almost alone as a representative of the serene and exquisite methods of the old school. Her hand, despite its sixty years, seems as pliant as a girl’s, and sure as clockwork. Her facility is amazing, and her technique beyond what is ordinarily assumed to be perfection. Withal she possesses extraordinary magnetism… Her final numbers were a berceuse of Slavic Colour, composed by her brother Franz, and played with the mute: and a florid number by Bazzini, "La Ronde des lutins." Technically, this was her crowning number. Her harmonics were as sweet and liquid as a bird’s song: her rapid pizziacti work was amazing, and her staccato passages were marvelously clean. In short, Lady Halle is an artiste who compels superlatives.

At the age of sixty, Wilma announced her retirement and intention to teach music in Berlin. Although the majority of her performing career was over, she was still greatly beloved by the public. In 1901, in recognition of her many achievements in music, Queen Alexandra bestowed upon her the honorary title of “Violinist to the Queen.” A coalition of royal families came together - among them the royal families of England, Sweden, and Denmark - and presented her with the keys to a palazzo outside of Venice. In 1907 she played at the memorial concert after the death of Joseph Joachim, the violinist to whom she had been so often compared throughout her lifetime.

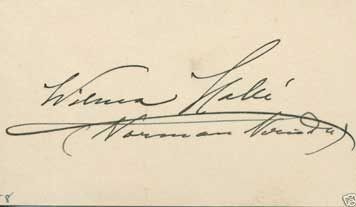

Wilhelmina Norman-Neruda, later Lady Halle

Wilma died of pneumonia in Berlin in 1911. She was seventy-two. Although musicians mourned her loss, they also celebrated her extraordinary life and achievements. Thanks in large part to her example, women across the world began to take up the violin in ever-increasing numbers. The next generation of violin virtuosos had a much higher percentage of women, all of whom accomplished amazing things in their own right: Marie Soldat (1863/4 - 1955), a protégé of Brahms and a fierce exponent of his violin concerto; Gabriele Wietrowitz (1866 - ?), one of Joachim’s most distinguished students and founder of a widely acclaimed ladies string quartet (few know that Brahms's violin concerto came to prominence largely because of the championing Soldat and Wietrowitz did of it); Maud Powell (1867 - 1920), who was not just the first great female violinist from America, but the first great violinist from America, period; Teresina Tua (1867 - 1955/56), who drew audiences to concerts by wearing diamonds and jewels on her extravagant gowns; Irma Saenger-Sethe (1876 - 1958), a student of Ysaye’s who served as his substitute at the Brussels Conservatory when he was away traveling; Leonora Jackson (1879 - 1969), an American violinist whose patroness was First Lady Frances Cleveland; Marie Hall (1884 - 1956), the dedicatee of Vaughan Williams’s Lark Ascending and the first person to ever record the Elgar concerto; Kathleen Parlow (1890 - 1963), one of the first great instrumentalists from Canada and one of Auer’s first North American students; Jelly d’Aranyi (1895 - 1966), the dedicatee of Tzigane and the two sonatas of Bartok…

And the list goes on and on.

It’s tragic that historians have largely forgotten the tremendous contributions of Wilma Norman-Neruda and the women who followed in her footsteps. Without their hard work, we modern-day listeners would regard the playing of such phenomenally talented women like Hilary Hahn, Sarah Chang, and Julia Fischer in a very different way. Not to mention the many women - soloists, orchestral players, chamber players, and amateurs - who might not have taken up the violin if there had been an “unfeminine” stigma associated with it. Perhaps a day is coming when these extraordinary women who trail-blazed for the rest of us can be properly remembered, honored, and celebrated by a wider audience of music-lovers.

Marie Hall

Leonora Jackson

Kathleen Parlow

Irma Saenger-Sethe

You might also like:

Replies

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

June 10, 2010 at 11:54 PM ·

I've been enjoying your articles a lot, thanks for it! Keep up the good work!

www.manfio.com