Anyone ever use a carving duplicator?

If I was a luthier, and wanted to make a living at it, I'd get one of these....

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1t2v0eBS3E&feature=related

Comments?

Replies (16)

I've known of a few people who use something like the duplicating router in the video.

I experimented with one about 30 years ago, and concluded that for me, it was faster to do it by hand. Doing it by hand also involved less risk, less noise, and made less of a mess.

I also know of a few people who have CNC setups (computer controlled, where the machine moves on its own). How widespread this is, I don't know. There are two or three places which offer the service to makers. You send them a piece of wood, and they return a semi-finished plate, carved according to specs or a sample you have furnished. That saves the maker the expense of the machine, the space, and the learning curve of knowing how to program and use it.

It's hard to get a lot of information on this. If a maker is "high-end", or claims or implies that their instruments are hand made, using a CNC isn't exactly something they would brag about. I know of one high-end maker who owns one, but I kind of stumbled across this information. It wasn't volunteered.

The machine in the video is displayed in the commercial vendor area at the larger violin making conventions.

I started my making career in a shop with 20 makers and a pantograph. No one would use it. The general consensus was that it didn't offer a real speed advantage when you factored in the noise, vibration, sawdust in shoes and pockets, and general feeling of danger and stress.

CNC now is different in that you can anchor a piece of wood in and stand back. The only person I know who has extensive experience with it started with CNC before he knew how to use tools, but since then has drifted away from it, telling me that working directly with the wood isn't really that hard, and is more fun.

http://vimeo.com/groups/94110/videos/20491079

0:27 to 0:31 is my shop.

There is something continental about that clip.

Interesting feedback, thanks.

As I kind of predicted, there is a "stigma" associated with using machines to create violins. I would think that the machines excel at getting to a basic shape, and then the final work is by hand. Especially if someone is "tuning" the plates. As I would think there are variables based on the density of the wood, fineness of the grain, moisture content, that can only be compensated for by hand.

What also boggles my mind is the neck is all carved (correct me if I'm wrong). I would think as long as the wood is hard, stiff, relatively dense, they would be more consistant in size, shape, so why do all that work by hand. If I was going to make a neck, at a minimum, i'd be spending time at the bandsaw, then use a router to round over the neck and do some carving then hand-sanding.

I still think that duplicator was really cool (the price as unfortunately impressive as well)

Appreciate your perspectives.

Sorry for any omissions. Necks and scrolls can be brought close to final shape by machine as well.

Expanding on a machining stigma, is there something better about live music, rather than a machine or recording backing up the opera or ballet? I happen to think so, and I'm willing to pay more for it.

You can buy pre-carved necks very close to finished if you want.

I don't think of it as much as a stigma as an impracticality, an inconvenience, and an expense. Kind of like an electronic fork. You'd have a hard time convincing me I needed one, even if it was electronic. Adding a computer to it wouldn't make it any better for me, either.

I've used both a pantograph-type duplicator and a CNC router, neither of which are currently in use in my shop. The space required, the noise, the mess, and the maintenance were significant drawbacks, in my opinion. With the duplicating carver, I once routed out the tops and backs for three cellos in one long afternoon. It was faster than I could have done it by hand, but far less satisfying. I was a nervous wreck to boot.

As a maker who makes a lot of experimental designs, it is more suitable to work the wood by hand. A lot less dangerous too. When you have a carbide-tipped cutting head screaming at over 20,000 rpm just a foot or two from your eyes, neck, and other vulnerable parts, it convinces one that some things might be more trouble than they're worth.

If I were doing a run of 20 plates, then yes, a machine makes a lot of sense, but that's not what most of us hand-makers are about. It's not a bad reflection on any maker who might use a machine to do the rough and heavy work; after all, in earlier times the apprentices did most of this work, not the master.

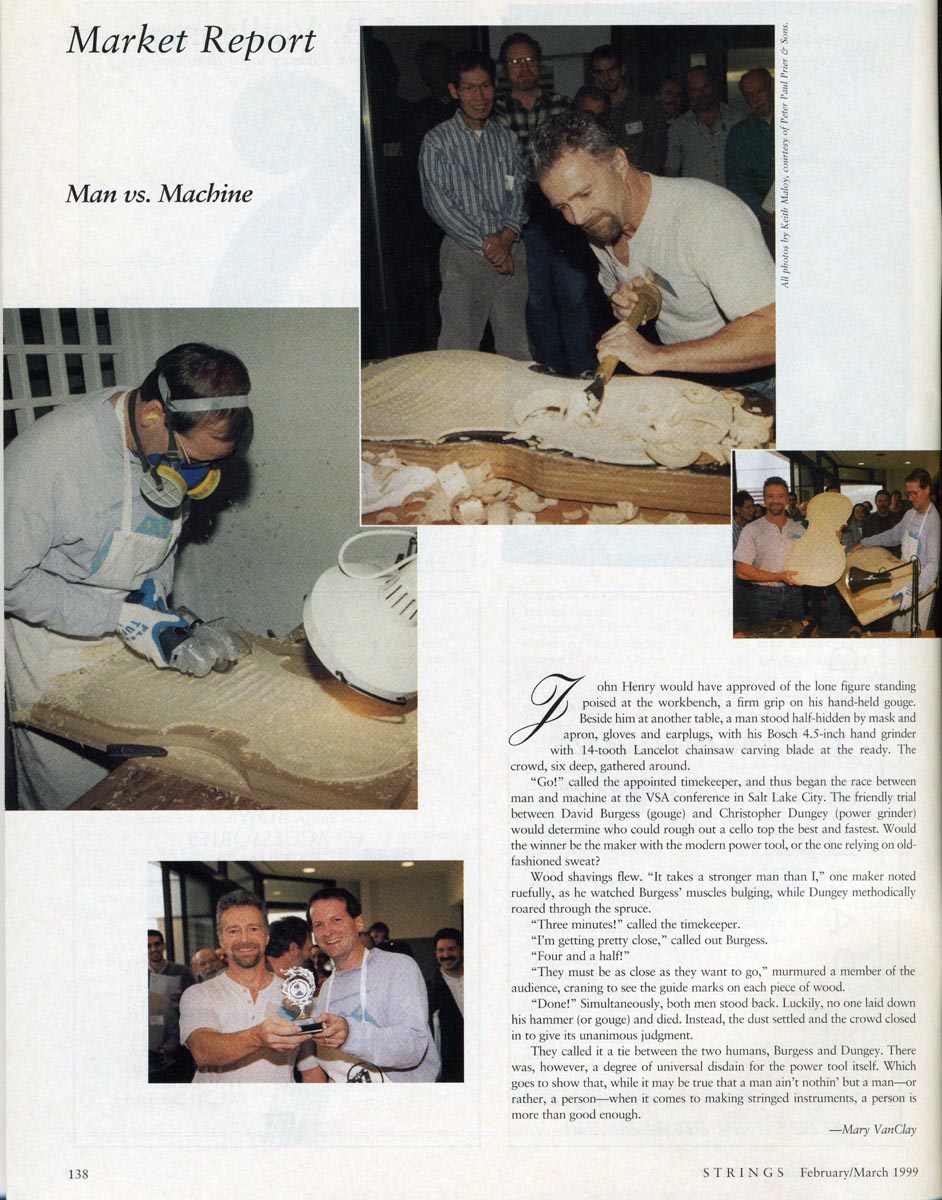

You may find this interesting or entertaining, from Strings Magazine:

David,

Impressive, that you came within 1.5 minutes of an angle grinder. Certainly nothing matches the peace and quiet of hand tools (planes, chisels/gouges)....but I still assert only retirees can do hand-cut dovetail joints.

As for the live music analogy, I certainly prefer live music myself (even a recorded concert) over any studio recording. Music is about emotion, tension, feeling, that can only be conveyed thru variations that can occur in tempo, accents, improvisation, and of course facial and body expressions, that is simply absent in a studio recording. Perhaps your point is that the machine doesn't have as much emotion as a human being.......can't argue that.

How much time were you guys racing against?

Bill, if I understand your question correctly, there was no time limit, except that an hour had been allotted for the demonstration. We both finished in under six minutes.

The demonstration was about bulk material removal, and that is where machines, in most minds, have their greatest value.

I should mention that what we did would be followed with small shaving planes, and then by scrapers. We may have gotten most of the wood removed in six minutes, but the fine tuning could have taken as much as another 40 hours, depending on a maker's methods.

In other words, it is the 95/5 reality: 95% of the problem is solved in 5% of the time, but it isn't right until the last 5% is completed, using the other 95% of the time. Seems to work that way in many endeavors :-)

I use CNC machines, but in a much different context. When exact duplication is desired with a material that is 100% consistent (e.g. metal), it is the way to go. With wood, you can really only do rough cuts due to the nature of the wood itself being variable. Even then, things can go awry.

In a mass production environment, it would be useful and cost effective, but for any instrument I would buy, I'd be looking for something done entirely by hand. The machines aren't sensitive enough to adjust to the variations in wood and I'd be concerned about latent stress fractures.

David,

My understanding is most luthiers never (or rarely ) use sandpaper, Is that true?

if so, do you know why that is?

Sandpaper is universally used on the neck and fingerboard to give a perfect and smooth surface. Most makers also use it for final shaping and smoothing of the outermost edges. Heavy use on the entire exterior tends to be associated with amateur or factory-type work. It's faster and easier for one who isn't skilled in the use of traditional cutting tools, but leaves a different surface, and tends to obliterate the features left by these tools, including the definition and crispness.

As it turns out, one of the most efficient ways to faithfully replicate the best 17th and 18th century work (so far) is to stick to their tools and methods, for the most part. If one is only interested in producing "a violin shaped object", there's much more leeway, and there are much faster methods.

There's no reason to think that 17th century makers didn't have sandpaper, but it probably would have been awfully expensive, and hence used sparingly. Think of the labor that would have been required to make something as cheap and common (today) as a pencil, prior to the manufacturing era. We find original ink marks, pin pricks, and scribe lines on the old instruments, but no pencil markings.

This discussion has been archived and is no longer accepting responses.

Violinist.com is made possible by...

Dimitri Musafia, Master Maker of Violin and Viola Cases

Johnson String Instrument/Carriage House Violins

Subscribe

Laurie's Books

Discover the best of Violinist.com in these collections of editor Laurie Niles' exclusive interviews.

Violinist.com Interviews Volume 1, with introduction by Hilary Hahn

Violinist.com Interviews Volume 2, with introduction by Rachel Barton Pine

September 22, 2011 at 03:01 AM ·