We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference

Violinist.com editor Laurie Niles' coverage of the biennial Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference in Minneapolis.

Master Class with Brian Lewis at SAA Conference 2012

By Laurie NilesJune 3, 2012 17:56

Brian Lewis is one of those few people who can say that he studied with both Shinichi Suzuki in Japan and Dorothy DeLay at Juilliard. The son of longtime Suzuki teacher Alice Joy Lewis, Brian is now professor of violin at the University of Texas.

Watching Brian Lewis teach is among the world's more enjoyable pleasures, so of course, I had to see his master class at the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference last week.

He taught four young students from all over the United States.

Brian Lewis with Finian, Maya, Serena and Benjamin

First up was Benjamin, from Minneapolis, who played the last movement of Wieniawski's Concerto No. 2 in D Minor. The piece begins with a flourish, a wild race up the fingerboard.

"Wieniawski was a wild man," Brian explained. "He had a girlfriend in every city, he drank a lot of er, milk…he even gambled away his Guarneri del Gesu violin once!"

At the beginning of the movement, he wanted Benjamin to "react to the piano, GO!" Then after the wild race up the fingerboard comes the crest and the descent.

"Have you ever fallen down the steps? Tripped on the carpet?" Brian asked. When you do, it goes something like this, "Ow……Ow……Ow…Ow…OwOwowowowowowow…" Until you get to the landing, which in this case, is that low "A" on the G string.

"Let the bottom 'A' be your goal," Brian said. "The 'A' needs to be the completion of all this virtuosity."

And speaking of virtuosity, Brian has a saying on his wall: "Virtuosity is not about speed; virtuosity is about control." So true!

One of the big techniques to bring under control for this movement is spiccato, which is done at the balance point, plus about two inches. The right hand must be flexible, but "too much flexibility will give us ON the string. Let's have a little more strength in the bow hand," Brian said. Spiccato is simply legato that is off the string.

Brian had him do an exercise, using Perpetual Motion doubles: first play it scrubby and ugly, on the string; then let it go off, and keep alternating between the two.

Next, Maya, 12, from Rapid City, South Dakota, played Paganini Caprice No. 20. Brian's first piece of advise for everyone was to be sure to study an urtext edition (an edition with the composer's original markings) such as Henle, as major competitions are requiring the use of these editions.

A bit of history about the infamous Niccolò Paganini: "He didn't actually sell his soul to the devil, but the story did help him earn some money," Brian said. Paganini's best friend was the great opera composer Rossini, and "they were so famous, they couldn't go out, so they would dress up as beggar women."

He advised that students study all the Paganini Caprices, but "find which of the Paganini Caprices are yours, the ones that you will own your whole life," he said. You only really need two of them for competitions; pick two that suit you, and learn them very, very well.

He said he once played Paganini Caprice No. 5 for the Juilliard teacher Dorothy DeLay, and when he was finished, she said, "Honey, you got 95 percent of the notes." He thought she was complimenting him -- not so! They spent the next two and a half hours combing through the entire caprice, from the last note to the beginning.

Finion of Ithaca, N.Y., played de Beriot's "Scene de Ballet," Op. 100. Brian pointed out the appoggiaturas -- that is, the notes that don't belong. "The notes that don't belong are the fun notes," Brian said. Sometimes they are upper-neighbor notes, coming from above, or lower-neighbor notes, coming from below. In either case, lean on those notes to bring them out.

Serena of Glen Ellen, Ill., played the first movement of Wieniawski's Concerto No. 2 in D Minor, and they talked about the importance of deciding what to emphasize most.

"You keep slowing down on every mountain," he said to her. "You have to decide which mountain you want to have the picnic on."

Also, this movement requires up-bow staccato, and up-bow staccato requires a lot of work. You can still perform the piece while working on this technique, after all, "The audience doesn't know you are working on it." But making up-bow staccato a strong part of your technical tool box is a long-term project. Dorothy DeLay recommended Kreutzer Etude No. 4, "Every day, for one year!"

But it's worth it. "It's through acquiring technique that we become free to make music," Brian said.

Ideas from John Kendall's Teaching Legacy

By Laurie NilesJune 3, 2012 15:36

Suzuki pioneer John Kendall was not just a teacher, he was a teacher of teachers.

A number of those teachers who benefitted from Kendall's wisdom gathered at the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference last weekend to present some of those ideas from their mutual mentor, who died a little more than a year ago.

Suzuki teachers Christie Felsing, Carol Smith, Susan Kemptor, Kimberly Meier-Sims, Allen Lieb, Margaret Shimizu and Vera McCoy-Sulentic

When it comes to the Suzuki movement in the United States, John Kendall was a major player. Kendall pioneered the teacher training program, he organized the first Suzuki Institute, he started the Suzuki newsletter, and he was crucial in getting the Suzuki books published in English. He was literally a farmer, and "he was more of a planter than a harvester," said Carol Smith.

So many of ideas are now widely used in string teaching, they don't even seem new or unusual any more, she said.

One of his ideas was to use the pieces that students know to build technique, she said. "Be your own Sevcik," Kendall would say. In other words, you can make up your own technical exercises, building on pieces already learned, which fits with Suzuki's idea of review and repetition.

Susan Kemptor, who wrote the first review of Kendall's book of memoirs called Recollections of a Peripatetic Pedagogue, said that "every time I met with John Kendall, I learned something."

Kemptor spoke about Kendall's saying, "Teach by principles, not by rules." While rules are precise and process-oriented, principles are more slippery and result-oriented, allowing for more experimentation. Discussing and experimenting helps us to become better teachers and learners. "We don't do something because someone else tells us to do it, we do it because it works," Kemptor said. "Value the process, experiment with the process, and all of us will benefit."

Teacher Kimberly Meier Sims spoke about Kendall's saying, "Finger, Bow, Go!" A violinist prepares finger and bow before moving with the bow. Inserting these preparation breaks in practicing can help a student get their act in order; if the fingers go after the bow, we know that the result is a mess!

Allen Lieb spoke of Kendall's fondness for "unit practice"; in fact, Kendall sometimes joked that unit practice was one of the three great discoveries of man, besides the wheel and fire. It's important to stop and set things up for correct repetition, to isolate patterns and not to practice mistakes.

Another favorite of Kendall's was to "reduce it to open strings," said teacher Margaret Shimizu.

It's almost always possible to isolate a bow stroke and to play it on one note. Margaret held up a piece of paper on which Kendall had written, "Life and violin playing is a series of alternatives."

Vera McCoy-Sulentic spoke about the idea of teaching the big muscles first. "Playing the violin happens with the back," Kendall used to say. The more one can use those larger muscles, the less the strain on the smaller ones.

You might also like:

- What is the Suzuki Method?

- Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference coverage

- Download all the Suzuki Violin Book recordings -- for when you can't find the CD!

Parker Elementary Suzuki Strings: How to Make It Work in a Public School

By Laurie NilesJune 3, 2012 14:23

I was chatting with a group of teachers at a reception when I realized that the school group playing in the background was actually playing the Corelli Christmas Concerto. More specifically, they were all playing the more-difficult solo part, by memory, playing it WELL, and they were all younger than fifth grade!

We were witnessing the results of a Suzuki strings program at Parker Elementary School in Houston, Texas, a music magnet public school since 1975. A group of about 50 violin and cello students and their teachers and parents had traveled to Minneapolis for the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference, to play for us and tell us about their program.

Certainly, here is an example a success story, applying and adapting the Suzuki method to a public school setting. Their performance also included an arrangement of Scott Joplin's "The Entertainer," Brahms' "Hungarian Dance," and a tango piece -- as well as a half-dozen pieces from the Suzuki Books one through five.

Impressed with their performance, I sought to learn more at a presentation the next morning given by Parker Elementary teachers, administrators and parents. Here are some features of their strings program: it consists of about 150 violin students and 50 cello students, who are accepted into the program as kindergarteners or first graders and go there through fifth grade.

Each student receives a 15-20-minute private lesson during the school day and a 40-minute group class every day. A parents is required to attend the private lesson, take notes and help the child practice at home, just like in private Suzuki lessons. The school provides instruments to those who need them, and the students remain with the same private teacher through fifth grade. Group classes are divided according to level, with about 30 to 40 kids per class. They all learn to read music, and they have a lot of public performing opportunities.

Teachers spoke about some of the things that have helped keep this program alive and thriving for nearly 40 years.

"Integrating our current culture into the Suzuki method helps make it sustainable," said violin teacher Elizabeth Benne. Cello teacher Lisa Vosdoganes creates many of the arrangements, which give violins and cellos equal opportunity to play melody and harmony. They incorporate the learning of many songs outside of the official Suzuki literature.

It's also important to tie lesson plans to core subjects: English, math, science, etc. Unfortunately, no school board in the U.S. will buy into the idea of teaching instrumental music for the sake of music's inherent worth as an academic subject. They need to know that the instrumental music program will help the school meet the English standards, math standards and other things considered a priority to the district and state.

"Write out lesson plans that integrate those standards," advised the Parker teachers. They showed an example of a lesson plan for teaching the song "Lightly Row" which included a list of more than a dozen ways in which the plan aligned with "Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills" standards in the areas of English, math and science. (These included listing the specific numbers and sections of the standards, with explanations such as: students use relationships between letters and sounds, students understand elements of poetry; student distinguished between declarative and interrogative sentences; students use concrete models to represent fractions; students understand force motion and energy….)

In other words, you have to constantly justify your music program, and in concrete ways, even if your program has been running for nearly 40 years and is wildly successful.

Also, Frequent public performances not only motivate students and help them become more confident players, but they also help raise the profile of the program within the community, making community members more likely to support it.

"When your program is given opportunities for exposure, take them!" said one of the teachers.

Parent Melanie Rosen said that "the Suzuki method has been a huge connector at the school. In a program like this, you are committed, whether you work or not. It's a unit, a team." Parents come to school for the lessons and wind up meeting other parents and becoming involved in other ways with the school. "The Suzuki method has been very strong in our family, and in building our school community," she said.

Parker Elementary principal Drew Houlihan said that having this kind of program involves an aligned commitment of time, teachers, finances, students, administrators and parents. The school has 900 students, 50 percent of which are on the free or reduced lunch program.

"In a time where every state is facing budget cuts, what is the first to go? Music and fine arts," Houlihan said. "At Parker, we give the gift of music to students every day. I think Suzuki in the schools is well on its way to a bright future."

Here is a recent performance of the Parker Suzuki strings students, playing Brahms' "Hungarian Dance":

William Starr: the Most Important Thing

By Laurie NilesJune 2, 2012 13:41

"The most important thing a teacher can have is EMPATHY: how does it feel, when you don't know how to do it?"

William Starr, Suzuki pioneer who is a faculty member of Boulder Suzuki Strings.

Laurel Trainor on Music and the Mind

By Laurie NilesJune 2, 2012 12:53

Musicians know instinctively that the study of music enhances our thinking and communication skills, but how can we prove that to school boards that want to cut our programs, politicians who view music as a "frill," and a society that views music as entertainment, with no concept of music as a discipline for serious study?

Perhaps if we can present some solid, scientific proof, we can take our argument farther. Dr. Laurel Trainor, a professor in the Department of Psychology, Neuroscience and Behavior at McMaster University in Ontario, is assembling just that kind of body of work. She is Director of the McMaster Institute for Music and the Mind, which recently received a $6 million grant from the Canada Foundation for Innovation for the scientific study of music. She spoke to us at the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference about her studies so far, and what discoveries they have made about how music affects the brain.

"From a very early age, infants have certain musical preferences," Laurel said. "One of those is for consonance over dissonance." She showed a video in which six-month-olds listened to Mozart, then to dissonant patterns. The infants clearly lingered over the Mozart, whereas they turned away quickly from the dissonant sounds.

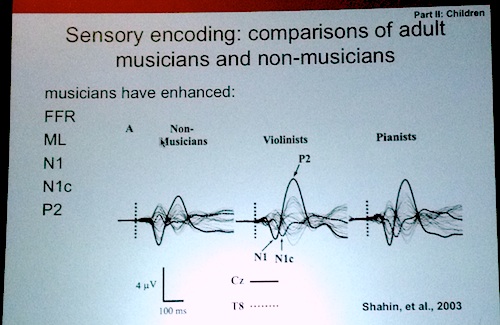

Another interesting discovery her team has made was that a short amount of listening to a certain timbre enhances the encoding of tones in that timbre. For example, a child who has listened frequently to guitar music is better able to process guitar music than he is able to process the same tune, played on a marimba. The brain changes neurally to process those tones. Also, musical enculturation happens very early. "What infants are hearing, really matters," she said. "Your brain, from listening to Western music, will become specialized for Western music. Already by one year, this enculturation process is happening." Musical training actually accelerated infants' acculturation to Western tonality. "The environment in which they are raised has a big effect on their musical learning." With one year of Suzuki training (yes they studied Suzuki students specifically), a child's musical discernment was significantly greater than their peers with no musical training. "So music lessons accelerate the acquisition of musical skills," she said. That may be obvious, but it's good news that science bears it out. But not only that, musical training had an effect on children's burgeoning reading skills. "Even controlling for age and socioeconomics, there is a correlation between how long they have been taking music lessons and their reading ability," Laurel said. This plays out in the adult brain as well; "it's clear that non-musical and musical brains differ," Laurel said. Check it out: I'll be very honest with you, I'm not sure about the specifics regarding the above chart. But clearly it shows that violinists have enhanced FFR, ML, N1, N1c and P2 (whatever those things are). It makes me feel quite brainy! But I'll try to explain it as Laurel did: the brain has more feed-back than feed-forward capacity. In other words, it has the ability to take in things, but it has even more ability to process those things. What this means for music is that "if you know what to listen for, you can hear it better." This power of the brain to review, analyze and anticipate based on past experience is called "executive function." Musical training effects "executive function" development, and those functions were found by this scientific team to be "two to three years advanced in kids who are taking Suzuki." I look forward to hearing about the results of their experiments in the future, and I hope that having some scientific proof will help us in our endeavors to create a more musically-educated society.

A big part of being a teacher -- particularly a student's first teacher -- is understanding how to lay the groundwork for the advanced techniques that student will need, years in the future. To this end, a number of sessions at the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference were aimed at dissecting advanced literature and pulling out the techniques and approaches that a student can start building from the beginning. (Here's a fun example: Did you know, the first "Twinkle Variation" was designed to teach the bowing that appears at the beginning of the "Bach Double"?) Giving a keynote lecture called, "Advanced Student's Explorations of Interpreting Bach," was Katie Lansdale, who has recorded all the Bach Sonatas and Partitas, performed all of them live as a cycle more than 12 times, and also won the Schlosspreis for Performance at the Salzburg Mozarteum for her performance of Bach. Katie was once a Suzuki student of Ronda Cole's, and now she is on faculty at the Hartt School of Music in Hartford, Connecticut, as well as a member of the Lions Gate Trio and founder of a school outreach program called Music for 1,000 Children. We began by talking about the music of Bach in general, then moving to specifics. "How smart was Dr. Suzuki to thread Bach through all the books?" Katie said. "You see a braid that keeps twisting back and back to Bach." When it comes to the Solo Sonatas and Partitas of Bach, that repertoire can be very intimidating to students, because "teachers have taught students to fear these pieces and put them at the top of a mountain. Instead, make these pieces a gift to your students. It's their world of inquiry and personal choice. I think this is a highly malleable repertoire." What techniques must teachers cultivate early in their students, so they can successfully play the Bach Solo Sonatas and Partitas? (You might want to have your S and P book handy for this…) Generally, a student will need flexible fingers in the bow hand. In fact, "nowhere do we need it more than in Bach." For example, a number of movements, especially Finales, have motoric rhythm, or 16ths that go on and on. "The only way to play that fast is with tiny muscles." Another important concept to understand is "release," in other words, the music must have "swing" or as the Germans say, "schwung." "It don't mean a 'thung' if it ain't got that 'schwung.'" Katie said with a smile. Slow movements run the danger of losing their hierarchy of beats, and with that, the "schwung." The word baroque literally means 'pearl,' as every pearl is different. It also refers an ornamented style, in art, architecture or music. Many of the slow first movements in solo Bach are highly ornamented, and this can get in the way of finding that "swing." The preludes in the Sonatas (titled "Adagio," or "Grave") "lay out the carpet for the fugue" in the second movement. Though these are slow movements, what does the student encounter, on first sight? "They encounter a lot of ink, a lot of notes," Katie said. No kidding, check it out: It's not easy to count that, but that's among the first steps. "We have to get the math straight before we find our way to freedom," Katie said. For example, the bassline is quite elegant -- if you can find it! -- in the first-movement "Grave" in Sonata No. 2 in A minor. It starts on an "A" and descends by step, until it reaches the subdominant D, then elegantly modulates to the dominant by raising to a D sharp, then ascending to E. Basically, it sounds really cool when you clear away all those notes. She wrote it out for us, reducing all that ink to seven simple quarter notes. "It makes for a beautiful musical underpinning; it simply goes stepwise," she said. All those notes are decoration, ornamentation. "We want that sense of being free within the beat. If we can find the spine or the skeleton of the music, it's usually a big relief to the students. They can finally see the forest for the trees." It's important to feel that simplicity, even with the addition of a lot of complex notes, woven in with hard-to-count rhythms. She also deconstructed the first movement "Adagio" of the Sonata No.3 in C major, which blooms harmonically, by measure; and the Sonata No. 1 in G minor, which has a simple melody at its core. Here are a two reminders Katie gave us, about playing chords: 1. Playing on two strings takes no more bow weight than playing on one. 2. Playing a chord takes no more muscle than playing a single note, it's just at a different angle. That sounds simple, but many students will press and crunch and wonder what's wrong, rather than simply lifting the arm to the proper angle. Another genius aspect of Bach's Sonatas and Partitas is in the way he manages to make one violin play several voices at once. Considering the limitations of the instrument, one has to work to pull this off. For example, in all the fugue movements, one has to bring out two, three, and even four voices at once. For the music to make sense, one must pick which voice to emphasize, then understand the technique for doing so. One technique Katie demonstrated was what she calls "tip backs." That's when you hold the bottom-string note longer than the top string note, in a chord. "By holding the bottom string longer, our ear is directed to the lower voice," she said. "It may feel like standing on your head for the first time." Also, if a lower note is a bass note, it should go on the beat, not before, and then have a light release, so to emphasize the bass note and not make it sound like a grace note. Another difficulty in the fugues is simply memorizing them. Katie shared some strategies: First, it can help to look at the map; that is, study the music away from the instrument. "Send the student home to find the themes," she said. She said she once had a student delineate the themes and episodes with different-colored pencils, returning to her lesson with her music looking like a rainbow work of art. But it makes sense to have different colors, or different visual representations, for each voice. "Your approach is different if you think of four different voices, rather than the same voice appearing in four different places," she said. For example, she often tells students to think of the opening of a fugue like it's a family argument. It also helps to create an aural appetite for the piece -- "The more you fall in love with a piece, the faster you learn it." You can be creative and use imagination in describing the episodes of the music. Students can practice without the bow; sing in their head; memorize the fingering; and practice from the end of the piece, learning the last chord and backing up from there. In auditioning potential students, she listens for the shape of the phrases and the message in the music. "I would rather hear Bach with shape and effect and an emotional message, rather than perfectly clean but lacking in shape," Katie said. You can also introduce students to the other places where these fugues occur: the G minor fugue was also an organ piece (BWV 539); the A minor fugue, a keyboard piece; the E major Preludio, the prelude to Cantata, BWV 29 for organ, strings, timpani and trumpet. Use what ever bowing works to bring out the right voicing in a fugue. Those other versions of the pieces, with other instruments, can be a guide. For example, Bach's C major fugue, from the Sonata No. 3, was actually based on a Lutheran hymn, with the words, "Come holy ghost, come here." Knowing that it was sung, and knowing the content of the words, can be helpful. By the way, the C major is also the longest fugue Bach wrote for any instrument! She also suggested arpeggiating soft chords instead of playing them organ-like; "This is something that holding Baroque bow inspires you do to." One person in the audience (me), asked Katie how she felt about period performance and the early music movement, in regards to Baroque music. "I'm totally fascinated by the early music movement," Katie said. She also said that she has a Baroque bow, though she doesn't consider herself a practitioner of period performance. She said she feels "gratitude that there are people immersing themselves in this study," and that we should soak up their discoveries like sponges. "You can play with heart and conviction in any style -- they pieces work in so many ways." After her lecture on Bach, Katie performed, and regrettably I missed her performance! (William Starr was giving a lecture, how was I to choose?) My colleagues raved about her performance, and fortunately, I will remind you, you can still hear it by getting her recording of the Bach Six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. Clearly Katie has exceptional stamina; after her lecture, and after her performance, she also gave a masterclass on Bach! Here's a rundown of that: First we heard the "Loure" from Bach's E major Partita, played by Maryanne, 17, of Ohio. "You are supposed to feel the gesture in your body," Katie said. "Don't lock any part of your body." If you bend your knees for strong notes (which she was doing a bit), the bow has to chase the violin. Instead, think of the violin as being on one plane, and "try to enjoy how tall the violin is." The Loure is the most serene movement of the E major Partita, and Katie suggested adopting what she called the "Adagio body." Since "adagio" literally means "at ease," we can imagine what this means. "It's also a little dangerous to change strings by changing the level of the violin," Katie observed. Instead of bringing the violin string to the bow, bring the bow to the violin string. "Loure," being a light dance, doesn't need the thick carpet of sound that a Romantic piece would need. For example, the Tchaikovsky concerto calls for endless vocal sound in its introduction. In the violin pieces of Mozart, bow changes are articulations, not connectors. The "Loure" is less sustained and can have more of a swing, like Mozart. The upbeat can be kind of a lift. In those cases when trying to bring out the lower voice, "if we think about the left hand, vibrating the bottom melody, it helps us bring it out. If you bring out the imitation more clearly, it's really a duet, it's no longer solo Bach." Next, Sofya, 15, of Colorado, played the Gavotte and Rondeau from the E major Partita. "I could hear your lively thinking all the way through," Katie said. (I love how Suzuki teachers compliment -- always specific and true, never empty praise.) "You really convinced me this is a bouncy piece in two." But Katie took issue with the tempo. Here, she drew examples from "Gavottes" in the Suzuki books (and there are many!), playing each one at the tempo Sofya had played the Bach Gavotte. Indeed, it seemed a bit slow. "Sometimes the ideas can get in the way of the long line," Katie said. "Telescope your ears back, so you hear the whole phrase." She advocated a faster, simpler approach. Then they checked the hard part at the fast tempo -- "We have to make sure that it swings at this tempo," Katie said. Even though it's a faster tempo, "the feeling of this piece is never in a hurry." It worked. She also talked about the dissonances being "juicy blueberries -- we want to enjoy how they're tart." At another point (m 74-77) she advised, "enjoy the laughter in it, and maybe it can be two voices." She also advised having direction, as if you are "wandering through the forest, but always see the end of the path." Being aware of Bach's original bowings (and one can find the manuscript in the back of the Galamian edition) can also give one ideas. "Trying Bach's bowings is always informative," Katie said. "It may not necessarily be what you do in the end, but they can inform what you do."

Time for Three is one of my favorite things happening on planet Earth these days, and Sunday night I finally saw this trio perform live for an audience of about 1,000 at the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference in Minneapolis. Their performance -- which I'd sum up with the words "smokin' hot!"-- was a source of both inspiration and affirmation for the appreciative group of teachers assembled from all over the world. The trio represents all that Suzuki teachers wish for their students: that they grow up to show a generosity of spirit and joy in music-making, and that they emerge fully at ease with both their playing and their own musical message. Both violinists in the group started as Suzuki students. The trio consists of bassist Ranaan Meyer and violinists Zachary de Pue and Nick Kendall. Nick is the grandson of John Kendall, a major pioneer of the Suzuki movement, who died last year. Nick's childhood Suzuki teacher, Ronda Cole, sat in the audience. "Nick comes from this Suzuki world," Ranaan told the audience. "He has brought that into our group and we love that." People ask what kind of music they play, but it's pretty hard to pin it down. "We don't know what we call ourselves, but we hope it's fun and meaningful," Nick told the audience. The three started jamming together while studying at the Curtis Institute ("great football program there," Nick said), and they create their arrangements by improvising on music they like: the Bach double, pop songs, fiddle and jazz standards -- you name it. The show began with tunes called "Of Time and Three Rivers" and "Thunder Struck" (no doubt they played this in sympathy with the raging thunderstorms outside!) and Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah." Their style takes advantage of their virtuosity and easy command of their instruments, full of effects like pizzicato, strumming, chopping, bariolage, glissandi, super-smooth legato, and the general ability to play outrageously fast and impeccably together. I was pleased they played one of my favorites, their arrangement of Hide and Seek, a harmonically interesting slow song by the British pop singer Imogen Heap. The original tune sounds almost unbearably electronic -- an intentional effect. I like the original, but I love their version: the way they shape it, relieve the electronic edge and just make something different and beautiful. About 1,000 smiles erupted on 1,000 faces when they launched into their jazzy version of the Bach Double. As if Nick and Zach's 150 mph tempo and off-kilter rhythmic jags weren't enough, bassist Ranaan stole the show, standing between them, registering every bounce of this musical tennis ball on his face, plucking out a jammin,' jivin' walking bass and swiveling his hips. They said that one time they were caught practicing that version of the Bach Double by Curtis professor Seymour Lipkin, who asked, "What was that?" When they told him it was the Bach Double, he said, "Too fast!" Speaking of Bach, the group also shared one of its more recent (and unrecorded, as far as I know) arrangements: their take on the Chaconne from the Bach D minor Partita, which they call, "Chaconne in Winter." As they tuned, Nick took a little longer with an uncooperative D sting. He may have been struck with a moment of self-consciousness, tuning his fiddle in front of 1,000 string teachers. "Still not right," he quipped. "Teacher!" He thrust his violin and bow toward the audience, as students do for tuning. We were still laughing when he crossed his right arm over the left, as if to hand violin and bow into the correct hands of the teacher. Then up walked Ronda Cole, and the audience roared. Nick's Suzuki teacher! Back to Bach, the group dedicated their performance of their version of the Chaconne to the memory of both Shinichi Suzuki and John Kendall. The idea for a Chaconne jam came one day when Zach was warming up on the Chaconne, and then Ranaan started groovin' to the Bach on his bass. They flipped on a recorder and spent the next 45 minutes or so improvising on the Chaconne, then they used that material, and added some bits from Bon Iver’s "Calgary," to create their arrangement. Played in its original form, for solo violin, the Chaconne begins with a triple-stop D minor chord, followed by a lot of triple and quadruple stops, which can sound pretty aggressive and fraught. I enjoyed the gentle beginning that this trio was able to create, without having to break a chord over three or four strings. It allowed the piece to unfold: Zach wound the motor with running notes and bariolage, and as it grew faster the music felt risky and dangerous - kind of a rush! The piece famously switches from a minor to major key, in a passage that players tend to describe in almost religious terms. Here, that change to the major started with bass pizzicato, then the piece builds volume again. In fact, I thought I heard Vivaldi's "Winter" in there, though I can't be sure. Overall, their performance was incredibly athletic for its power, speed and control. The end of the Chaconne returned to that tranquil beginning. I found it rather enlightening to look at the Chaconne this way. After intermission, our heros showed a video they made called 'Stronger,' which has been circulating on the Internet for several months. The topic of the video is bullying, and then ultimately, empowerment. In the video, bullies use a young man's violin like a baseball bat, smashing it to pieces. But the geeky violin kid emerges victorious -- and respected -- after a successful performance in the school talent show. "All three of us have experienced these kinds of things. It's amazing to me that carrying around this double bass is not a cool thing," Ranaan said, laughing. "I look at it and think: cool!" He also mentioned that he calls his bass Xena -- "She's not only gorgeous, but she's so strong!"

When violin teacher and pedagogue Cathryn Lee graduated as a Suzuki teacher some 30 years ago in Matsumoto, Japan, Shinichi Suzuki had her recite a teacher pledge, which said in part: "We will continue to study teaching in the future, with much reflection, and through this continuing study we will be better able to concentrate energies toward better teaching." That's exactly what some 900 Suzuki teachers from around the world are doing this weekend at the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference 2012 in Minneapolis: continuing to explore teaching, music and community. Cathryn Lee talked about the teacher pledge at the first class I attended at 8:30 Friday, "Exploring Right-Hand Technique." We practiced a good number of bow exercises meant to strengthen bow strokes like martele, legato, staccato and more. They included circling the bow in the air, thumb pulses and even a few ways of holding the bow by the hair and then playing. Try it, it's pretty awkward! Next came a joint session called "Bach in the Books" with SAA President Teri Einfeldt of Connecticut and Colburn School faculty member Michael McLean of Los Angeles, which they described as "pedagogue meets composer," Teri being the pedagogue and Michael being the composer. It's important, even in the youngest beginner, that a teacher have a vision of that student as an accomplished player in the future. If we plan to teach our students the solo Sonatas and Partitas by J.S. Bach (and we do), certain techniques have to be well in place, starting very early in the Suzuki books. As Bach expert Katie Lansdale said later in the day, "How smart was Dr. Suzuki, to thread Bach through all the books? You see a braid that keeps twisting back and back to Bach." Those little Suzuki students eventually turn into sophisticated musicians, and Bach is an important part of their post-Suzuki books study: "This year I have 14 high school students who were once playing "Twinkle"; they are all playing (solo) Bach now," Einfeldt said. Teri mentioned a few techniques that students should be acquiring throughout the Suzuki books for their study of solo Bach later. For the left hand: learning to leave fingers down and to measure finger intervals (if they are a half, whole or larger step away from each other); lifting a finger to change its location; removing unnecessary fingers to avoid a grace note effect (say, one needs to go from a 3 to an open string, the 1 and 2 can be in the way); expanding and contracting the hand (she described a "finger pileup" for chromatic intervals in the hand); bridging the fifth (one finger over two strings, in tune); leaving fingers down for bariolage, ringing tones; double stops, chords and more. For the left hand, the student should come away from the Suzuki books with a strong idea of how to do various kinds of string crossings; playing comfortably at the frog and with control. Also a student must be able to vary bow speed. For example, "introduce them to the concept of phrase ending with any two-syllable word," with emphasis on the first vowel. For example, say "ICE cream." Fast bow on "ice," short soft bow on "cream." Also, lessons in phrasing and articulation that are learned in early Bach pieces will apply later. Michael McLean spoke about the hidden treasures in Bach, and how it's good for teachers to know about those details, even if every student may not be ready to receive the information until later. Michael's tremendous enthusiasm for the art of composing came through as he spoke about various aspects of the Bach pieces that appear in the Suzuki books: "Bach had a real pride of craftsmanship in his composing," Michael said. In Minuet 2, Michael emphasized that the bass part is extremely important, the way it runs in rhythmic counterpoint to the melody part. "A lot of students don't know the bass part in this piece," he said, "the melody rides on top of the bass." (By the way, the books Fun for Two Violins allow teachers and students to play these pieces together, with the kind of counterpoint and interaction Michael spoke about.) Michael also pointed out that in Bach's Minuet No. 3, the G minor part that appears in Suzuki Book 3 is basically the same as the G major part that students learn in Book 1: "It's like he cheated!" Michael said. "He was good at re-using material." He had superimposed both parts, so that we could study their tremendous similarity. He also noted that the Bach Gavotte in G minor from Suzuki Book 3 "is an amazing technical masterpiece," full of motives that are layered and inverted, in both the violin "melody" part and in the piano/orchestra/duet part. Personally, I agree; playing this piece as a duet with my students (using the books I mentioned above) is one of my great joys because we see the genius in the way Bach's musical motives are crafted. "It's like a tree by a pond -- the inversions are its reflection." Bach's genius was in his ability to calculate such things intuitively. His way of creating motives and putting them together "was so ingrained in him that it just poured out of him," Michael said. "He was like a kid in the sandbox, playing with his toys, and he was really good at it." Michael also pointed to the fact that there are rhythmic hierarchies in this movement; though it is written in a 4/4 meter, sometimes it changes to a sort of meta-meter in three, and one should become aware and go with that. "Sometimes the worst thing in music is the bar line," Michael said. "It's not telling you to stomp your fee every four beats!" Instead, it's just Bach's way of getting the ideas onto the page, and it may be part of a more layered and complex scheme. I love the fact that the Suzuki Method draws together so many talented teachers with different expertise, and also different ways of looking at the same music. While Teri showed us specific pedagogical points, Michael's wonderfully geeky (I mean that in a good way) deep knowledge of the composition of these pieces make them open for even more exploration. So good to be here, so good to be part of the Suzuki movement. And so far, I've shared only the morning of the first day! I have more to share with you, on Katie Lansdale teaching and playing Bach, your brain on music and much more. Stay tuned!

When I climbed into my airport Super Shuttle and William Starr and his family and then California teacher Idell Low climbed in right after me, I realized: This is going to be one very surreal weekend at the biennial Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference! It's the first time I've attended this biennial event, and I'm here in Minneapolis, Minn., with nearly 900 of my Suzuki teacher colleagues for a weekend of workshops, concerts, schmoozing and reuniting. There are more than 150 sessions in all, and at the moment I'm hiding in my hotel, trying to make a plan from the 80-page conference schedule! A few of the featured people besides Bill Starr: Teri Einfeldt, Brian Lewis, Time for Three, Barbara Barber, Carey Beth Hockett, Edmund Sprunger, Bob Philips, Russ Fallstad, Allen Lieb, Susan Kempter -- I'm not even getting the tip of the iceberg, here. So many wonderful people! It's hitting me, how much it will mean to me to see both the Suzuki star teachers and performers who are here to share their wisdom and talents, and to simply see so many of the friends I've made from my 20-year journey so far as a teacher. I'll see classmates from my very first pedagogy class I took at the University of Denver, colleagues from the two Suzuki groups where I've served as a teacher, friends I've made at Suzuki Institutes and other violin events, and even a good number of V.commie friends! I also plan to write about it, and share some of the fun with you, so look for my posts this weekend and next week.

Katie Lansdale: How to Teach and Perform Bach Sonatas and Partitas

By Laurie Niles

May 31, 2012 11:32

Bach G minor Adagio

Students Maryanne, Sofya and Katie Lansdale, after the Bach master class

'Time for Three' performs for the Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference

By Laurie Niles

May 28, 2012 21:39

Nick Kendall, with Laurie

Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference 2012: Cathryn Lee, Teri Einfeldt and Michael McLean

By Laurie Niles

May 26, 2012 10:28

Stephanie Ezerman of North Carolina demonstrates holding the bow by its hair.

Teri Einfeldt and Michael McLean

Suzuki Association of the Americas Conference 2012: So many people!

By Laurie Niles

May 24, 2012 17:14

There are some high-power folks here!

Minneapolis! The view from my room