We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Interview with William Hagen: From Suzuki Violin to the World Stage

In early May when he was in Southern California to play Max Bruch's Violin Concerto No. 1 with the Pasadena Symphony, violinist William Hagen sat down with a group of Suzuki teachers to talk about his violin journey: from being a Suzuki kid, to studying at The Colburn School, to the world stage as a soloist.

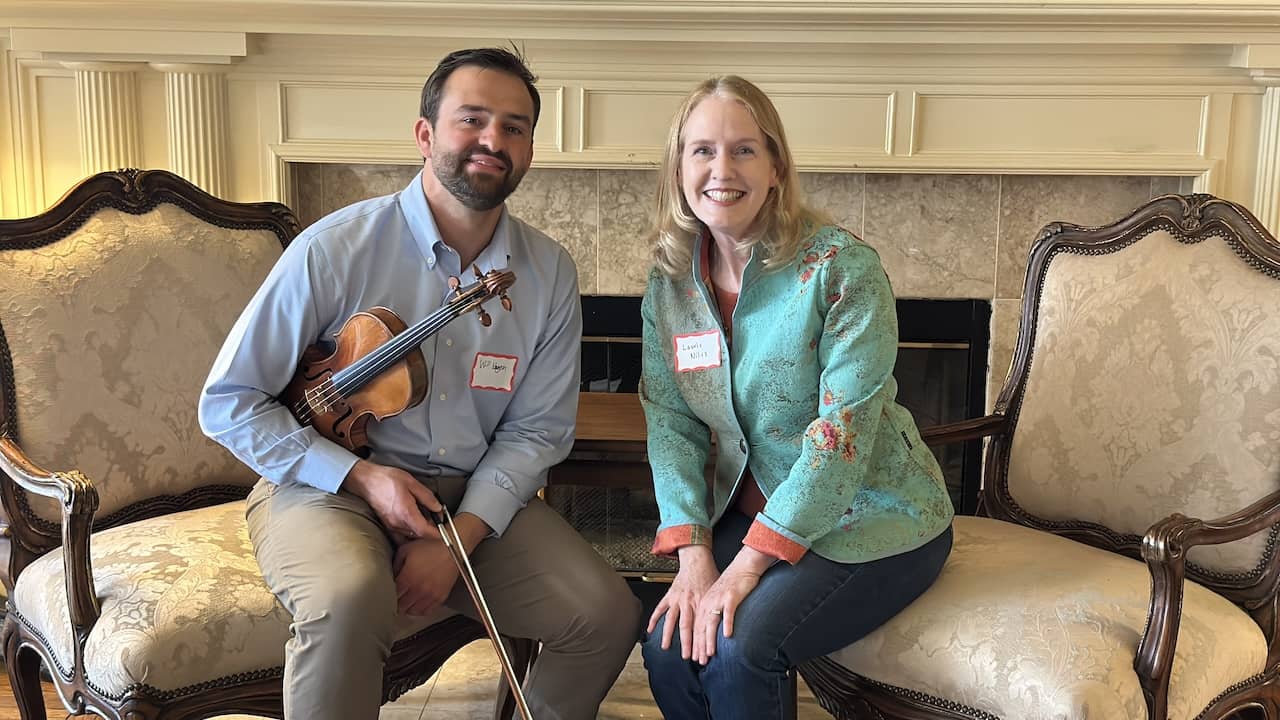

Violinist William Hagen, with the 1732 Strad violin he plays, and Violinist.com's Laurie Niles.

The gathering was sponsored by the Suzuki Music Association of California's Los Angeles branch and was organized by fellow violin teacher and SMAC-LA President Carrie Salisbury, and I had the honor of doing the interview.

Hagen currently lives with his wife and young son in his hometown of Salt Lake City, Utah - but he was happy to be back for the week in the Los Angeles area, a place he considers a second home, after his many years studying at The Colburn School - "so many memories, and so many familiar faces!"

Over the last decade, Hagen has traveled the world, making a name for himself. A third-prize winner at the 2015 Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, Hagen has performed as a soloist with the Chicago Symphony, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Detroit Symphony, Frankfurt Radio Symphony (HR Sinfonieorchester), San Francisco Symphony, Seattle Symphony, Utah Symphony, and many others around the globe.

Hagen told us that it all began when he heard a violin at church, at age three. He was so taken with it that he started begging his parents for a violin - begging intensely.

"Apparently the begging lasted longer than the normal 20 minutes - so it must have made a huge impression on me!" he told us. They relented, and by age four he had started violin lessons.

While his family was interested in music, no one was a professional, and "the whole classical music world was a foreign thing to us."

He started his lessons with Natalie Reed, a violinist in the Utah Symphony who had studied with Josef Gingold. "She didn't teach many beginners, but she taught me." He then went to Deborah Moench - known in Suzuki circles and beyond - "she's just kind of a legend."

Hagen played baseball and was a devoted fan of the Utah Jazz basketball team, and his early aspirations revolved around the sports that his family loved. During football season he entertained the fantasy of being a quarterback.

But those goals turned out to be a stretch - literally. "My mom's 5'3 and my dad is 5'8, and I thought, 'I'd like to play power forward for the the Utah Jazz..'" Hagen said, laughing. "So I would drink a lot of milk, stretch at night - that didn't work out!"

He did play baseball for a long time, but then one day he heard the great violinist Itzhak Perlman perform, and that was it. He had a new hero. Hagen already had been playing the violin for a while, but at that point "I thought, I really want to do that."

"I was always passionate about the violin, from the start, and I loved the sound of the instrument," Hagen said, "but something about hearing Itzhak Perlman play turned it into a childhood obsession."

Something Hagen remembers from his Suzuki years was his teacher Debbie Moench, with her abacus, "insisting on doing something correctly, and repeating it," Hagen said. "At the time, it seemed so tedious, but now that I'm in my 30s, I'm obsessed with that!"

"She was really good at simplifying, presenting a clear goal, along with a clear way to do it," Hagen said. It's a system that still works for him. "If you have a clear goal, something do-able that you can achieve, then you get a clear result."

I pointed out that sometimes people talk about Suzuki being fun for when you're little, but then when you want to get serious, you need to go to a teacher with discipline. However - it sounded like there was quite a bit of discipline and rigor in Hagen's Suzuki upbringing. Was that true?

"There was rigor, and there was major tension with that," he said. While Hagen did not have a "stage mom," his mom did insist that he do the work that his teacher assigned. She presented it like any other school assignment: "Mrs. Moench the violin teacher said to do this 50 times, in the same way that the math teacher said to complete a certain homework assignment."

So there was rigor, and there was fun. "The rigor was in the repetition, and doing things right," he said. "The fun was in the group classes." He remembers playing in Rocky Mountain Strings - "this army of violinists on stage," he said. Holiday performances, playing with other kids, working one's way up through the repertoire and getting to play the harder music - "it was such a fun thing to play in a group."

It was that combination of Mrs. Moench's rigor and the group's atmosphere of community fun that made it "a passionate, positive experience," Hagen said.

At a certain point, Hagen realized that not only was he learning to play the violin, but he was actually excelling at it.

When he was nine, he participated in the Utah Symphony's annual "Salute to Youth" concert. Students first auditioned at the Utah State Fair, then if they passed that round, they auditioned for the chance play a movement of a concerto with the Utah Symphony at Abravanel Hall.

After he played his initial State Fair audition, he summed up his performance for his grandparents "I don't think I was the best, but I wasn't the worst," using a line from one of his Berenstain Bears books. He was just happy to have made it through the audition process.

But then it turned out - maybe he was the best - he actually won!

"Until then I had no idea that the violin was something I excelled at," Hagen said. "It was something I liked, something I knew I could do - but at that moment I realized, this was something I could really do."

"That was my first time, playing with an orchestra, when I was a little kid," Hagen said. "It wasn't like watching baseball players, or 6'9 Karl Malone or all these guys on the T.V. Those things were so far away - this was tangible. I actually stood in front of an orchestra and played with them! It gave me the encouragement to really pursue it, it showed me that this was something I could really get serious about."

Following that experience, his former teacher Natalie Reed helped him connect with Robert Lipsett.

Hagen was just nine when he auditioned for Lipsett, the Colburn School violin pedagogue who has achieved almost legendary status for his high-level teaching. But at the time, Hagen didn't really know who he was - fortunately!

"I thought I was getting a master class with him, he thought it was an audition - and that's the best way to have an audition!" Hagen said, to much laughter from the teachers in the room. "It's perfect, if you don't even know it's an audition!"

"So I guess I passed the audition to get into his studio - which I didn't know was happening - and then I studied with him for the next seven years," Hagen said. Studying with Lipsett required extraordinary devotion from Hagen and his family. For the first five years, Hagen and his mom would fly from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles on Southwest airlines every single week for lessons.

What was it like to study with Lipsett?

"It was probably scary, he's just a physically big guy!"

But beyond that...

"If I could point to the number one thing about his teaching that made the biggest impression on me and influenced my playing - putting aside the fact that he is great at teaching the violin - it was that I felt like he really liked my playing," Hagen said. "More than anything else, I think that is the best thing we can do for a student - and for a colleague if you are playing chamber music. The best thing you can do - to get the best sound, to get the best performance from a person - is to like their playing and to make sure they know that.

How did Lipsett let him know that?

"He would just tell me: this is a strength for you, this is a weakness for you," Hagen said. "He would let me know when things were going well, and he would give me ironclad confidence."

For instance, they worked for a very long time on a certain Kreutzer etude, to get a good martelé bow stroke. "I think he took more pride in that martelé stroke than I did, because he taught it to me, and he really worked at teaching me that stroke," Hagen said.

Hagen hasn't stopped learning from Lipsett, he said. "I still call him. What I really like about his teaching is his no-nonsense approach: 'That's the cause of the problem, do that.' There's no mystery - he has simple solutions to seemingly difficult problems."

But it was also about holding him to a high standard, and persisting even when it took time and work.

"Not giving up is the best vote of confidence," Hagen said. "I always felt like he was a big fan of mine, that he liked my playing, that's massive. But if somebody takes the attitude, 'Oh yeah. We should probably give up on this,' that's it. It may seem like, yes, let's go on to sunnier, greener pastures - but it can be kind of cutting for a kid. They feel like 'Oh, I've failed at this.' Mr. Lipsett never gave that impression."

Something specific he picked up on with Mr. Lipsett: "He doesn't accept 'three-fingered' violinists," Hagen said. "You can watch really big soloists, who hardly ever put a strong note on the fourth finger, hardly ever vibrate on the fourth finger." It's very common- because it's the weakest finger, the hardest to vibrate on. "He would insist, he would absolutely not budge, the student was going to put a fourth finger on that difficult, hard-to-vibrate note."

"Sometimes this would last a year, a year and a half, two years - a student getting onto a fourth finger and faltering because that finger wasn't strong enough," Hagen said. "And then their junior recital would come, and boom! They had this big, fourth-finger vibrato."

"I loved seeing that," Hagen said. "Studio class was a huge part of studying with Mr. Lipsett, and seeing people, over the course of weeks, months, years - develop something in their playing that seemed impossible to develop - really inspired me."

Were the students fans of each others' playing, within the studio?

"It was an unbelievable studio to be a part of - Nigel Armstrong, Jeff Meiers, all the Calidore Quartet - I could go on and on. All these really great players," Hagen said. "There's definitely competition out there, but luckily throughout my time, I've noticed that there is a really good feeling that we're all in this together.

After seven years with Lipsett, Hagen went to Juilliard and studied with Itzhak Perlman - once his idol! for several years. Then he came back to Colburn. "I honestly just really missed it a lot - I love LA."

Hagen also told us about his journey with an instrument - at this point he plays on a Stradivari violin.

"It's really important to play on a good instrument," Hagen said. "Now, I don't think 'good' and 'expensive' actually match up, I think we really exaggerate how much the price or value of an instrument applies to how good it sounds." When it comes to fine instruments, a new violin tends to cost less then a several-hundred-years-old antique, and "there are so many amazing modern instruments."

What is the first thing Hagen looks for in a violin? A big sound.

A violin with a "great sound" but not a "big sound" might work for someone who is not a soloist, but as a soloist and chamber musician, it's been important for Will to find a violin that has a big, powerful sound.

"As a soloist, having a big, powerful violin helps me more on the low dynamics than the high dynamics," he said. For example, I noticed that in his performance of the Bruch concerto with the Pasadena Symphony, he was able to create a mesmerizing pianissimo.

He said he remembers listening on the radio to the German violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter play the Bruch live at Carnegie Hall, "I was so inspired, she was playing so softly, it was absolutely memorable. It was so beautiful," he said. "But if your violin is quiet already, that takes away the chance to do that."

"A lot of times with modern instrument we think 'Aww that's so loud' - but it's not a bad thing. You can really cultivate an ability to play quietly on that loud violin, and people will still be able to hear it," he said.

When it comes to the string of violins he has played, "I've been so lucky."

As a child, he had a nice violin from Robert Cauer Violins.

Then when he started getting into the really fancy violins - Amati, Guarneri, del Gesù, Strad - he was grateful to have Lipsett's help in sorting through the choices.

"There is so much placebo effect that goes on with an instrument," he said. In other words, if you know you are playing an expensive instrument by a well-known maker, it affects how you think about it.

"I'm the worst bow shopper in the world - in the shop I'll think, this is a magic wand, the best bow I've ever played on, and then I'll step outside, and after playing the first note I'll think, 'This is a baseball bat.' So it's nice to have Mr. Lipsett telling me "That sounds great" - he said it, I don't have to worry about it."

His first high-level fine violin came from the Mandell Collection: a 1665 Amati, "It was a really great instrument." The next violin was a 1675 Andrea Guarneri. "I was playing on that violin for the Queen Elisabeth Competition at the beginning of my career," he said. Then in a master class at Colburn School, Gidon Kremer told him he had outgrown the violin and needed a better one.

At that point he was loaned a Guarneri del Gesú (the 1735 'Sennhauser' Guarneri del Gesù) from the Strad Society. (Hear him play "The Lark Ascending" on that instrument here) However, it had an extreme wolf (B natural on the G string) - a problematic note. It also didn't produce the big sound he needed for soloing with orchestra.

"If you have a gorgeous sound but nobody can hear the sound, then that's a problem," he said. It forces you to dig in "and that changes the sound - it's like a forced whisper instead of an actual whisper."

He found his current instrument through violinist Rachel Barton Pine, who has the same manager. Her foundation had a Strad that no one was using, the 1732 "Arkwright Lady Rebecca Sylvan" Strad. When he first played it, the entire G string was unplayable - like a wolf on the entire string. But the other three strings "were the best I'd ever played, just unbelievable." He went to a luthier, who adjusted the violin, "And then boom, amazing. I've had it since 2018."

Hagen went on to play some Bach for us on his violin - but unfortunately our Zoom recording did what Zoom recordings do - it cut out the sound of the violin as "superfluous noise"!

So I offer you this performance by Hagen with that Stradivari violin - from a recital at The Colburn School in 2022. I've cued it up to his Ysaÿe's Sonata No. 5 - because I love the glorious musical sunrise that is "L'Aurore" and he does it so well! It is also a solo work, so you really hear the violin's sound. You are of course welcome to listen to the rest of the program!

You might also like:

- Interview with William Hagen: Danse Russe at the Colburn School

- Master Class with Suzuki Violin Pedagogue Debbie Moench at The Gifted Music School

- William Hagen performs The Lark Ascending, on a 1735 del Gesù violin

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

May 15, 2025 at 12:14 PM · Thank you for sharing!