We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Violin Master Class with Christian Tetzlaff at the Colburn School

We violinists tend to focus on playing 100 percent "correctly," but when it is time to perform, "our job is completely different," said violinist Christian Tetzlaff. At that point - with the notes in hand - it is time to give the audience something that goes beyond precision - to enter the world of the composer and draw out the music's emotional content.

Violin Master Class at the Colburn School: Muyang Wu, Vivian Kukiel, Christian Tetzlaff and Andres Engleman.

This was a central idea in a master class Tetzlaff gave in early December at the Colburn School, appearing courtesy of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra (LACO), with whom he was performing the Brahms Concerto in a series of concerts that week.

The soft-spoken German violinist used vivid images to make his points throughout the class - encouraging students to find the "wild joy" in their playing, or to convey the pent-up energy of a "crouching tiger," or to remember the "human personality" in the music they were playing.

The master class opened with a performance by Andres Engleman of the first movement from Prokofiev's Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor - a mercurial piece that is in turns warm and melodic, and then zippy and fast-moving. Engleman had it well in hand - and Tetzlaff pushed for more.

"This is very serious and earnest," Tetzlaff told Engleman of his performance. "I need more colors from you, in every direction."

"Talk to us," Tetzlaff said, then he demonstrated, turning more toward the audience, not looking at the violin. "Put your head in front," he said, "open up."

Christian Tetzlaff and Andres Engleman.

The first theme - the warm and melodic one - requires thoughtful bow distribution more than it does outright projection. Keep it a little simpler, he advised. If we try to project too much, "we miss the simple sadness of those little changes," Tetzlaff said.

"You really have to enter Prokofiev's world," Tetzlaff said. In the beginning, "you sing," and then when the terrain gets rockier, "you do the opposite."

And speaking of those chunky octaves and double-stop passages, it can get boring if played too straight. "I don't hear any kind of wild joy!" It's important to enjoy the action of the passage, he said. "Long notes, short notes - simple joys!" Tetlaff said, almost dancing as he demonstrated playing an ascending double-stop passage.

It's important to really shape everything, to make sure that something syncopated sounds syncopated. Tetzlaff gestured as Engleman played, really urging him to pull more out of himself.

Next was a performance of Bach's solo Sonata in A minor, by Muyang Wu, who played the Grave with beautiful sound, nice voicing and excellent intonation, followed by a tidy and well-organized Fuga.

"It is really well-played," said Tetzlaff, following his performance. And let me interject - this simple complement is significant, coming from Tetzlaff, a master of Bach who has recorded the entire Sonatas and Partitas three times (in 1993, 2005 and 2017) and is held up for his interpretive genius, when it comes to Bach.

The "Grave" is a slow movement full of "ornaments" that could have been left to the performer, but in this movement the ornaments are all written out. Why? "Bach would always write out (the details) because he didn't trust us fiddle players," Tetzlaff said.

Christian Tetzlaff and Muyang Wu.

The opening is a four-voice chord, and it should be exuberant - "don't be too shy," Tetzlaff said.

Tetzlaff talked about the beginning, about how Bach avoids resolution - it's a way to create musical tension - by not saying it.

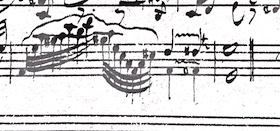

In the entire movement, he pointed out, there are just two triplets - these:

"...so do something with them!"

He also said that "the trick is to look at the bass line all of the time." Observe the bigger harmonic beats and "feel these in your body."

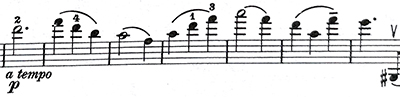

At the end of the Grave movement is "a memory of the beginning," Tetzlaff said, and he also said to think cello continuo here. The very last few notes of the movement are interesting in the manuscript:

What does that squiggly line mean? "You can do a bow vibrato, or you can do a trill," Tetzlaff said. "Both convey anxiety." Wu did a bow vibrato - a rapid quasi-portato "wawawawawa" with the bow. Tetzlaff shared he played this with a bow vibrato for 40 years and then changed his mind, and now does a trill. (You can hear the difference in his earlier and later recordings.)

They then worked on the Fuga, and Tetzlaff had Wu play just the theme, asking him to bring out the phrasing. "I want to know how you are phrasing it," he said, demonstrating and again, almost dancing as he played it.

In talking about a passage containing quadruple-stops...

...Tetzlaff pointed out the exuberance of the open strings. "We have these violinist joys," Tetzlaff said, "if something gets big (i.e. four strings) - enjoy it!'

When there are several voices, make them each a bit different, he said. Maybe one is more singing, more legato.

At a certain point Tetzlaff, violin in hand, hopped (yes hopped) down off the stage and had Wu play a long excerpt, all the way to the end of the movement, as Tetzlaff sat in the audience. It was beautiful playing.

Next, Vivian Kukiel performed the first movement of the Brahms Violin Concerto (the same piece that Tetzlaff would be performing the next day with LACO!) She gave a vigorous and accurate performance of this very thorny work - and of course, Tetzlaff wanted more.

"I encounter this in students, they take this very seriously," Tetzlaff said. "You are good enough to transcend this."

After the long orchestral introduction, the soloist's first entrance is emphatic and surprising, almost like a jump-scare, Tetzlaff said. And importantly, "It's a human personality, making this statement." To pull that off, one has to get beyond the idea of sheer accuracy and take risks.

Christian Tetzlaff and Vivian Kukiel.

Following this anxious and edgy entrance - which goes on for some time, the music at last reaches a D major resolution, a major change. "Feel it in your body, it is such a relief," Tetzlaff said. Make it noticeably different.

Upon arriving at this famous melody:

Tetzlaff quoted Joseph Joachim, the 19th-century violinist who was the concerto's original dedicatee, who implored violinists, "please don't go to 'adagio' when the piece has only just started." In other words, this melody should not settle too much, it should move forward.

Tetzlaff had a vivid picture to paint of this passage in the Brahms:

He told Kukiel that she was playing the triplets in a "very brave" way, but even so they still risk sounding "all the same." These have to lead emphatically to the double-stops, and here is where the bow is "like a crouching tiger," ready to pounce (with all hair) for those triple-stops.

It was a joy to watch Tetzlaff work with these young students - all already excellent players - presenting them with thoughtful and imaginative ideas that enlivened their playing on the spot, and giving everyone present a glimpse into Tetzlaff's unique artistry.

You might also like:

- Interview with Violinist Christian Tetzlaff: the Loving Hand of Brahms

- Review: Violinist Christian Tetzlaff Performs Brahms with LACO

- Violin Masterclass with Christian Tetzlaff at USC

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Tweet

Replies

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.