We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

The Founding of the Kenya Conservatoire of Music in 1944

A surprising set of circumstances - war, displacement, chance - led to the founding 80 years ago in 1944 of what eventually became the Kenya Conservatoire of Music.

I learned the story following the death of Bronislaw Fryling, who was my violin teacher in Johannesburg, South Africa, in the decade of the 1950s, my pre-teen and teen years. During lessons, Fryling, a Polish refugee and student of Otakar Ševcík, would talk about famous violinists he knew and other absorbing topics, but never ever spoke about his wartime background. I had absolutely no inkling of his experiences and, given what I later unearthed, would berate myself for being so remiss as to never ask him about his life when I had the opportunity.

When Fryling passed away in 1961, I inherited his collection of sheet music. This collection covered the violin literature in multiple early 20th century Russian, Polish and other European editions. There were also newer editions of 1940's vintage, intriguingly bearing stamps of a music store in Nairobi, Kenya. Among this mass of music I came across the original scores composed by another important character in this story: Giuseppe Gagliano. These were hand-written on stave paper, apparently supplied to POW camps by the Red Cross in East Africa.

Fast forward a few years. Stellenbosch University in South Africa initiated a project to digitize local Jewish newspapers covering the first half of the 20th century. While scouring this material for my book, Jascha Heifetz in South Africa, I came across a few articles on Fryling that documented his concertizing in South Africa. These articles also referred to his background, including his wartime deportation by the Soviets. Subsequent to this, I stumbled over reference to an oral deposition by his widow (who had emigrated to Australia) given to the Holocaust Museum in Melbourne. In this Oral History Archive she recounted what had happened to him.

One thing led to another. I found myself sucked into the background of Italy's war campaign in East Africa, along with the under-told story of Poland in WWII and the heroic exploits of one General Anders, with whose army Fryling managed to get out of the Soviet Union.

I hope you enjoy this story of a violinist refugee and a composer prisoner-of-war, and how their different paths came together in East Africa to initiate what would eventually become the Kenya Conservatoire of Music.

* * *

The Kenya Conservatoire of Music was founded in 1944. The prime movers in this saga were two musicians whose resilience and creative drive overcame the depravity of wartime horrors. One was a Polish violinist refugee who played a "Strad," the other an Italian composer prisoner-of-war, namesake of a Neapolitan master violin maker. Tossed into the cauldron of the War, their paths would cross serendipitously in East Africa.

Ironically, the masterminds of the War itself would make their unwitting contribution – the Conservatoire would not have come into existence were it not for the ruthless ambitions, betrayals and double dealings of Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini. This is the story of an extraordinary nexus of circumstances, starting for each of the principal characters on opposite sides of the Allied-Axis conflict.

From recent years: Symphony Orchestra of the Kenya Conservatoire of Music today. Photo courtesy Music in Africa.net.

War in Europe and Africa

Barely a month before the outbreak of war, Britain approached France and the Soviet Union to guarantee Polish sovereignty against German attack. But only the French came to the table. In a pre-emptive move just one week before Germany’s invasion of Poland, Hitler lured Stalin into a better deal – a non-aggression agreement between Germany and the USSR – the so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The bait dangled by Hitler was embedded in Secret Protocols in the agreement whereby Germany and the USSR would divide Poland between them.

The September 1, 1939 invasion of Poland by the Nazis triggered WWII in Europe. With the betrayal of "Peace for our Time" and Britain committed to come to Poland’s aid, discredited Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain would declare war on Germany two days later.

Half a world away, on June 13, 1940, Mussolini’s Italian forces launched an air attack from their East African Colonial Empire on the Royal Air Force base at Wajir in British East Africa. Britain quickly rallied her Commonwealth allies and by November 1941 the British-led forces had swept into the Italian colonies. They could claim the distinction, rarely heralded, of recording the first major Allied victories of WWII.

The British East African Campaign spelled the end of Italy’s East African Empire and doomed any Axis Power ambitions in East Africa. Thousands of Italian prisoners of war were taken and interned in British prisoner-of-war camps.

The Polish Violinist from Kraków

When the German army crossed the Polish border, the world of Polish-Jewish violinist and lawyer Bronislaw Fryling was about to be turned upside down. Born in 1904, he came from a musical family, claiming in support of his heritage that Vladimir Horowitz was his cousin. Fryling had studied with Otakar Ševcík, had concertized in Europe and had taught violin at one of the music schools in Kraków. He was a man of many parts. Aside from the violin, in his youth he had something of a career in auto racing, mixing it on the track with the likes of Germany’s Rudolf Caracciola and Hans Stuck. Armed with a Doctorate in law in the late 1930s, Fryling’s music career took a back seat as he defended Polish Jews against rising antisemitic attacks.

Polish-Jewish violinist and lawyer Bronislaw Fryling.

At the outbreak of the War, Fryling was in the front line of the Polish military. On September 13, 1939, just two weeks into the fighting, he was captured by the advancing Germans. By reportedly jumping from a train, he managed to escape and fled east.

Stalin’s Double-Cross of Poland

Fighting desperately on their western front, the Poles were stunned when, on September 17, 1939, the Soviet Red Army rolled into Poland from the east. Stalin had brushed aside the long-standing Polish-Soviet non-aggression treaty and stabbed Poland in the back. By virtue of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was to be dismembered and obliterated from the map. Poles were now fighting rear-guard actions on two fronts.

As a consequence of Stalin’s double-cross of Poland, moving east did not spare Fryling. He was captured by the Red Army. He and hundreds of thousands of his Polish compatriots came under the control of The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, the notorious NKVD. They were deported to the Soviet Union.

The Composer-Conductor from Italy

Back in East Africa, among the Italian POWs taken by the British was a seasoned Italian musician, one Giuseppe Gagliano. He had been born in 1912 in Sciacca and had begun his musical studies at the Alessandro Scarlatti Conservatory (formerly the Vincenzo Bellini Conservatory) in Palermo, followed by study of piano, cello and composition in Rome under Antonio Savasta, Mario Pilati and Ottorino Respighi. He became first cellist in various Italian orchestras and his compositions included an opera, "Village Market," staged in the United States, and "Pastoral Quintet," performed on Italian National Radio, with Gagliano himself at the piano. In the late 1930s, he was director of a traveling opera company. By the outbreak of WWII, he had been appointed an officer in the Italian Army in East Africa, organizing musical life in Asmara, the capital of the then-Italian colony of Eritrea. Captured in the military actions of 1941, the British interned him in Camp 351 "Kabete" near Nairobi.

Italian cellist and composer Giuseppe Gagliano.

Polish Deportees in the USSR

Soviet policy was to destroy the Polish military, remove its officer corps and Russify the civilians so as to eliminate any future military threat as well as any vestiges of Polish national identity. Polish deportees to the USSR who were not murdered by the NKVD were dispersed to concentration camps and prisons throughout the Soviet Union. The number of Poles so displaced has been estimated to be at least 325,000 and perhaps as many as 1.5 to 1.6 million.

In this bleak dispensation, Fryling fared better than his compatriots who suffered terribly in the Soviet camps. When the NKVD discovered that he was a concert violinist, apparently willing to work within the communist system, he was permitted to perform. Although Fryling later reportedly spoke well of the Soviet’s encouragement of the arts, it remains uncertain whether his concertizing in the Soviet Union was for private groups or public concerts in Soviet towns.

Churchill’s Deal with the Devil

At this juncture, events would be upended by a third betrayal, this time with Stalin at the receiving end. As an astonished world watched, the Nazis and their Axis allies marched into the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa was underway.

Once he had recovered from the shock of Hitler’s treachery, Stalin recognized that he desperately needed assistance, even from the hated capitalists. He no doubt recalled the British overtures that he had so expediently brushed aside in favor of Hitler’s pre-war pact. For his part, Winston Churchill, now Prime Minister, while having no love for the Bolsheviks, presciently recognized that the Soviet depth of manpower could help sap Nazi war stamina. As he later wrote, "If Hitler invaded Hell, I would make at least a favourable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons." Churchill concluded his deal with the Devil.

In August 1941, the strange new bedfellows moved against Hitler. Code-named "Operation Countenance," the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran secured the Persian oil fields against possible German threat while simultaneously protecting Allied supply lines from the Persian Gulf to the USSR.

Soviet desperation and British pressure induced Stalin to conclude a new agreement with the Polish government-in-exile in London headed by General Wladyslaw Sikorski. In the Sikorski–Mayski agreement of July 30, 1941 the Soviet Union pledged to waive the territorial claims of the Secret Protocols and free tens of thousands of Polish prisoners-of-war held in Soviet camps. From their ranks the agreement provided for raising a Polish army to fight against the German invaders. Fryling’s fortunes would be tied to this new army.

The Anders Army

Having decapitated the senior Polish officer corps, including the infamous Katyn Massacre, the Soviets scrambled to come up with a Pole who could lead this Polish Army in Exile. They eventually scrounged General Wladyslaw Anders from imprisonment in the notorious Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. He had somehow survived many atrocities.

General Wladyslaw Anders.

How General Anders managed to organize a Polish fighting force on Soviet soil is an epic WWII saga in its own right. His available conscripts were nothing more than emaciated survivors - clad in rags - of remote Soviet camps. When the British and the Poles would not agree to have this rag-tag force serving under Soviet command as cannon fodder at the front against the Germans, Stalin agreed to allow the army to leave the Soviet Union. He did not require much encouragement, being loathe to give this fledgling force any medical attention, food, clothing or supplies. In addition, having a large Polish army with no love for the Soviets in his back yard could frustrate his East European ambitions.

Exodus from the USSR

Though but a pitiful fraction of the original deportees, nearly 115,000 of the incarcerated Poles were evacuated to Iran under this arrangement. Against orders from London and pressure from Moscow, Anders adamantly insisted that Polish civilians be allowed to tag along with his Anders Army. As he subsequently wrote: "… either I could save the civilian population or leave it to its fate. Evacuation might mean that some would die in Persia, but if they stayed in Russia they would soon all be dead."

Of the 115,000 Poles who made it to Persia, 40,000 were civilians. Fryling’s status at the start of WWII probably aided his inclusion among those lucky enough to accompany the Anders Army out of the USSR.

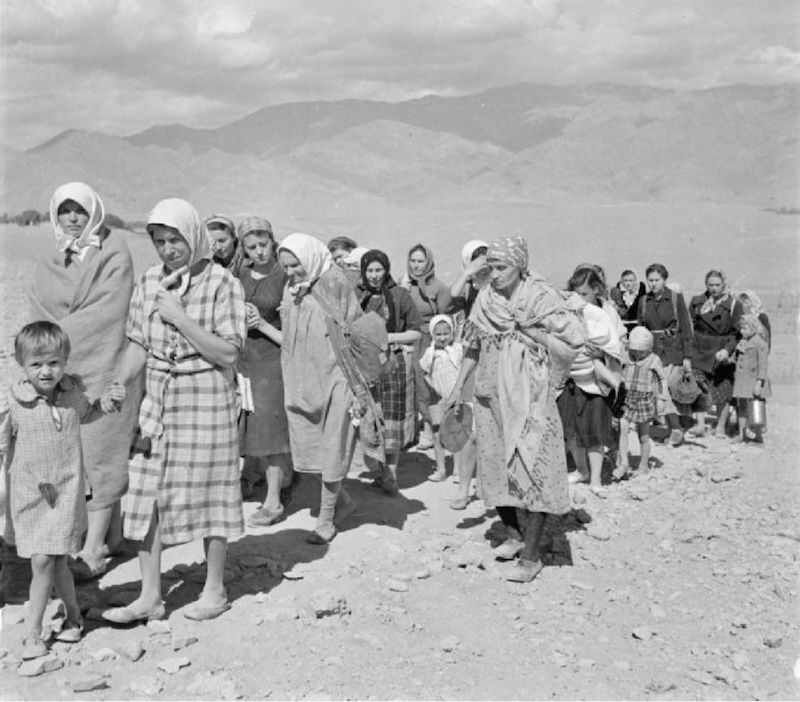

Polish refugees evacuated to Iran from the Soviet Union by General Anders. Photo by Terry Ashwood, No 1 Army and Film Photographic Unit, courtesy of the collections of the Imperial War Museum.

The Polish Army in Exile would eventually be trained in the Middle East and then distinguish itself as the Second Polish Army Corps fighting in Italy alongside the Allies as part of the British Eighth Army. Their morale was sustained through their traumatic experiences by the aspiration of fighting on the Allied side for a free Poland to which they could eventually return.

To spare the British military the burden of feeding and caring for 40,000 civilians close to theatres of war, they were dispersed from Iran by the British to far-flung outposts of the Empire. Fryling’s lot was consigned to a refugee camp in East Africa, along with several of his Polish countrymen.

The Camps in East Africa

Camp life in tropical East Africa was a far cry from the gulags of Siberia. Notwithstanding his refugee status, Fryling lost no time in making his mark in Kenya as a distinguished violinist. On May 3, 1943, the Theatre Royal in Nairobi was the venue for a celebration of Polish Constitution Day. In attendance were the Governor of Kenya and his wife, senior British military and colonial officers, the Polish Consul General, and several other Polish dignitaries. Fryling starred in the celebration, with his renditions of works by Polish composers, notably Chopin, Wieniawski, Karlowicz and Szymanowski. His playing was praised in The East African Standard and hailed as the highlight of the show.

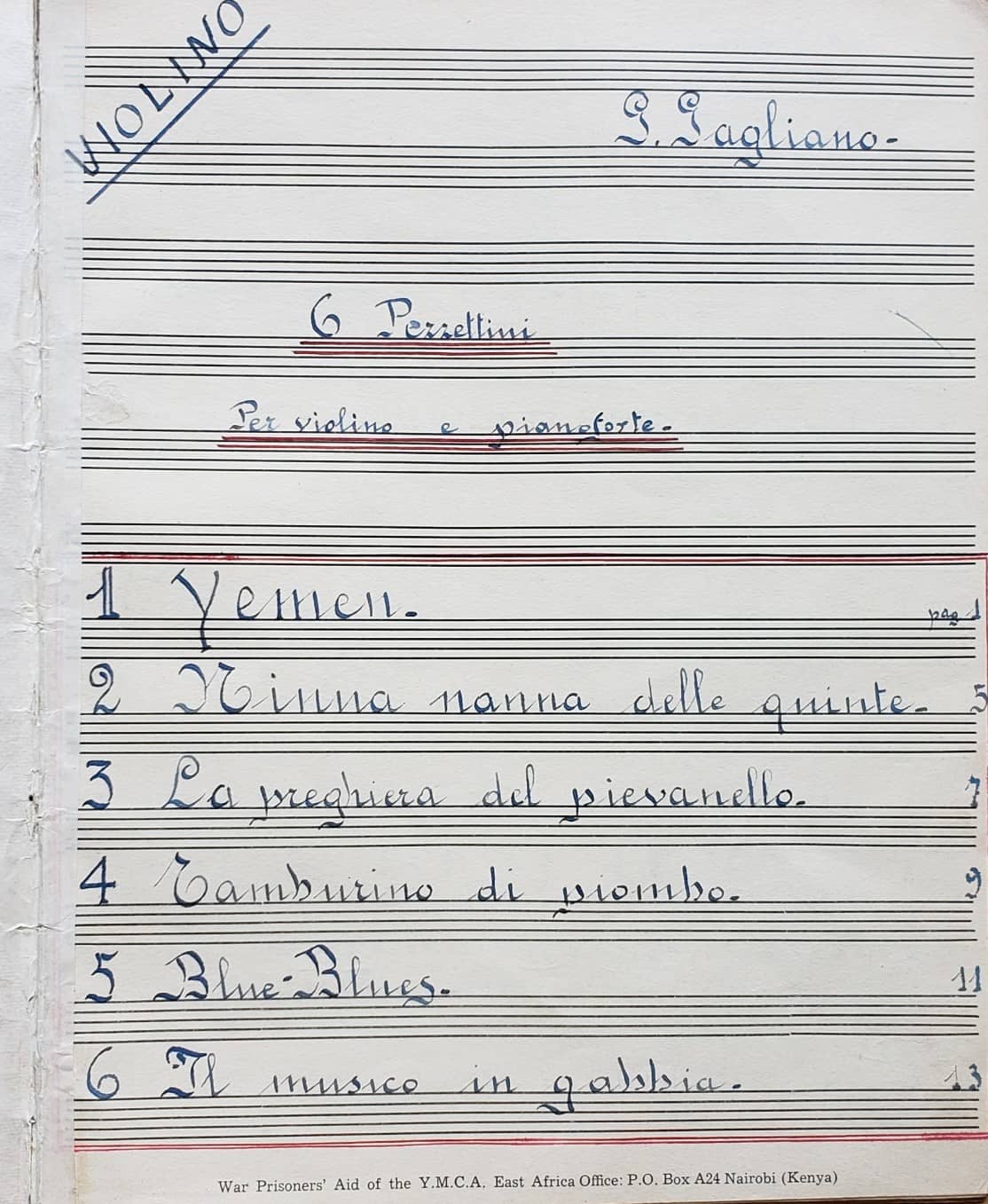

Meanwhile, in Camp 351, Gagliano was wrestling with how to marshal his musical experience and help his fellow inmates. The privations of camp life could also not stifle a composer’s creativity. Gagliano would while away boredom creating compositions on manuscript paper supplied to the prisoners by the local YMCA.

Title page of Gagliano’s 6 Pezzettini (6 Little Pieces) for violin and piano. Original manuscript handwritten on stave paper provided to the POWs by the YMCA in Nairobi. From the collection of Michael Brittan.

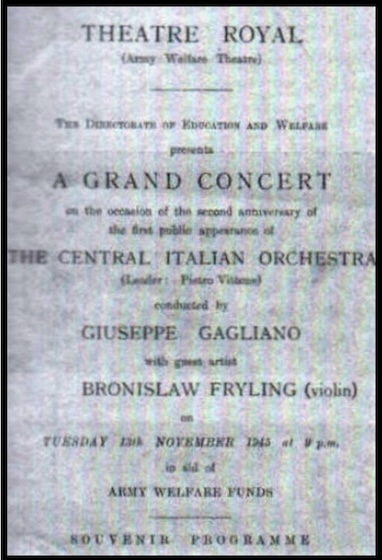

The power of music and the extraordinary conjunction of wartime circumstances would inexorably draw Fryling and Gagliano together. The refugee and the POW would play significant roles in promoting classical music life in what would eventually become an independent Kenya. Fryling helped Gagliano and his fellow Italian POWs to establish a camp orchestra. It became known as The Central Italian Orchestra (CIO) and scraped together instruments wherever it could.

The first concert of the CIO took place in the Theatre Royal, Nairobi on November 13, 1943, with Gagliano on the podium and Fryling as soloist. The East African Standard wrote as follows:

"Many of Gagliano’s players are not professional musicians but they provide an excellent example of what can be achieved by musicianship, orchestral discipline and competent leadership in a combination playing regularly together."

Under the direction of Maestro Gagliano, the Central Italian Orchestra would subsequently give as many as 200 concerts in less than three years.

Program of the second anniversary concert of the Central Italian Orchestra, Nairobi, 1945. Courtesy of the website Prigionieri in Kenia

The East African Conservatoire of Music

With classical music stimulated by the CIO, in 1944 Fryling founded the East African Conservatoire of Music, forerunner of today’s Kenya Conservatoire of Music. For facilities, the Conservatoire availed itself of three disused army huts. Fryling’s efforts were aided by Nathaniel (Nat) Kofsky, a violinist who had come to Kenya with the British military where he was appointed musical director of the Red Cross, and Billy Isherwood, a building inspector and ardent music lover who had founded the Nairobi Philharmonia Society in the 1930s. Fryling was appointed as the Conservatoire’s first director.

Although expatriates initially comprised the bulk of its teaching staff and students, the doors of the East African Conservatoire were open from its inception to people of all races, an adventurous and farsighted policy for its time. After a spell teaching at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, Kofsky returned to Nairobi in 1951 and was appointed director of the Conservatoire. At the helm for over three decades, he guided the Conservatoire through the difficult era leading to Kenyan independence and beyond.

Poland’s Fate

When hostilities in Europe finally ended in May 1945, what remained of Poland had been saved from fascist dictatorship, but not from Stalin. Though Poles had fought alongside and shared the sorrows and horrors of war with the Allies, the territorial spoils of the war had already been divided in accordance with decisions taken at the summits of Teheran and Yalta.

While President Roosevelt publicly praised the Polish war effort, General Anders would have been appalled had he been aware of the President’s utterings in private: "I have no intention of going to a peace conference and bargaining with Poland or the other small states… Poland is to be set up in a way that will maintain the peace of the world."

Churchill and Roosevelt had essentially bargained away the Polish independence for which Britain had gone to war, in return for Stalin providing the bulk of manpower – and casualties – fighting the Nazis. This realpolitik, if not exactly another double-cross, trapped Poland behind the Iron Curtain as a victim, not as one of the victors. Stalin had gotten much of what Hitler’s Secret Protocols of August 1939 had promised him.

Musical Aftermath

The last concert of the CIO before Gagliano and the orchestral musicians were repatriated to Italy was given in the Theatre Royal, on April 14, 1946. The program was devoted to Camp 351 works by Gagliano, including his violin concerto and "Tropical Melancholie" for violin. Fryling was once again the soloist.

Notwithstanding the repatriation of the POWs, the impact of this orchestra would spawn the Nairobi Orchestra in 1947.

With Poland in the Soviet communist camp at War’s end, the Western Allies completed their sellout by withdrawing their recognition of the Polish government-in-exile in favor of the communist government in Warsaw. Polish refugees in East Africa strenuously resisted repatriation to their homeland. Jochen Lingelbach describes the background to their plight: "The deportees had gone through terrible times in the Soviet Union, and even if they had not been anti-Soviet before, they must have become so in the labour camps and special settlements. Furthermore, over 80 per cent of the Polish refugees came from those Polish provinces that belonged to the Soviet Union after the war. Their houses had been confiscated following their deportation, and they would have been denied the right to return to the places they came from. Most of the Poles were thus stranded in Africa after the brief happy moment of the war’s end."

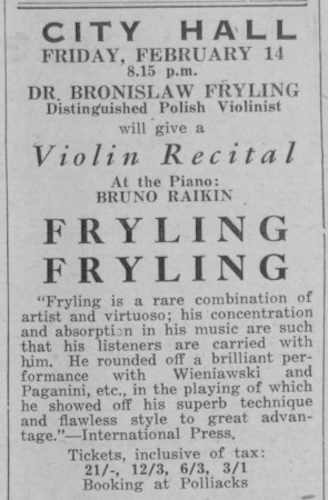

Providing them a refuge became a knotty problem for the British government. Unlike Gagliano, Fryling would not return to his native land. He managed to settle in South Africa where he concertized extensively, playing programs which covered a wide range of the solo violin literature as well as major concerti with orchestra. The publicity for these concerts included the drawcard of his instrument, reportedly a 1719 Stradivarius. The critics were warm in their praise of his musicality and technique.

Ad for recital by Bronislaw Fryling in the Johannesburg City Hall, February 1947. The program included the Brahms Sonata in A major, the Pugnani-Kreisler Praeludium and Allegro, and ended with a Paganini Caprice.

Fryling also used these concerts to introduce works composed by Gagliano in the Kenya POW camp. Under the heading "Polish Violinist," The Cape Argus of April 29, 1946, reported on a concert with the Cape Town Municipal Orchestra as follows: "Dr. Bronislaw Fryling, a Polish violinist, made his first South African appearance on Saturday 28 April 1946 in a performance of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto and Giuseppe Gagliano’s Violin Concerto in D minor, which had been dedicated to him."

The Gagliano concerto was played in a repeat performance on Thursday May 2,1946. Fryling performed again with the Cape Town Orchestra on September 28, and then, in a solo recital in the Cape Town City Hall on October 1, his program included the world premiere of Gagliano’s Fantasia D’Estate (Summer Fantasy).

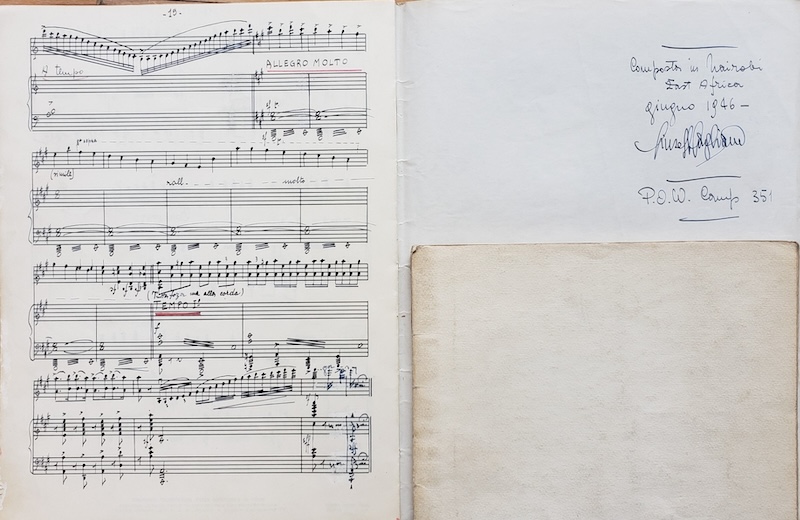

Last page, original handwritten piano manuscript of Gagliano’s Fantasia D’Estate (Summer Fantasy) for violin and piano, signed by the composer in POW Camp 351. From the collection of Michael Brittan.

In the 1950s, Fryling lived in Johannesburg and continued to pursue diverse interests. He went into business making canned foods and indulged his former motor racing exploits by trading in his Chevrolet for a more sporty Jaguar Mk1 2.4 newly introduced to South Africa in 1956. He gave me violin lessons on the side, frequently demonstrating on the Strad which was always reverently to hand. He never spoke about his wartime experiences but may well have swapped war stories with noted violinist Ruggiero Ricci, with whom Fryling socialized when Ricci toured South Africa in the 1950s. They would both have been well acquainted with Nazi and Soviet double dealings – Ricci was enlisted in the US Army between 1943 and 1945 employed as an "entertainment specialist," a euphemism for serving in a propaganda unit which provided background music for films dealing with the war. Fryling died of cancer in Johannesburg in 1961.

Back in Italy, Gagliano would pick up the pieces of his career. In August 1946, he placed second in an Accademia di Santa Cecilia national competition of conductors. Between 1955 and 1973 his appointments included Director of the Tolima Conservatory in Colombia, teaching composition at the Cairo University, teaching at the Giuseppe Tartini Conservatory in Trieste as well as at the Giovanni Battista Martini Conservatory in Bologna. He also had occasion to conduct the RAI Symphony Orchestras of Rome, Turin and Naples. As composer, he accumulated a significant list of published works of chamber and symphonic music, with awards in international competitions to his credit. From 1974 he taught at the Santa Cecilia Conservatory in Rome until his retirement. He died in Velletri on May 15, 1995.

Legacies

With the end of the War in Europe, Germany was defeated by the Allies and the Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union would begin. In East Africa, Kenya would gain its independence from the United Kingdom in December 1963. The following year, Kenya became a Republic and joined the British Commonwealth. The geopolitical repercussions of Iran’s nationalization of British Persian oil interests are still being felt in the 21st century.

Today, 80 years after its founding, the Kenya Conservatoire of Music honors its legacy as a non-profit organization providing teaching and performance of "quality music of all styles at an affordable cost." The faculty number approximately 35, almost all Kenyan. The Conservatoire offers several Diploma options for selected subjects such as conducting, teaching and performance. The Conservatoire serves also as the Kenyan representative for the Practical Examinations of the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, London.

The impact of the orchestra of Italian POWs lives on as the Nairobi Orchestra. Still playing today, this orchestra is one of the longest-lived amateur orchestras in Africa. Most of Gagliano’s compositions endure in his published works, some in a discography. Curiously, known works composed by Gagliano in POW Camp 351 do not appear as part of this bibliography.

Fryling’s violin pupils would continue the Ševcík-Fryling line, with reach into musical appreciation and ensembles such as the National Youth String Orchestra in the UK.

Following his death, the "Fryling Strad" became the subject of its own tale of intrigue. It was loaned for many years by his widow to prominent South African violinist, pedagogue and composer, Alan Solomon. While being cleaned one day by J.J. van der Geest, Johannesburg’s elder-statesman luthier, the Stradivari label peeled off. Underneath was revealed another label by noted Turin maker Giovanni Francesco Pressenda. Other than described as having being found in "a famous English collection" the origins of this instrument are obscure. It may be noted, however, that Pressenda’s designs, especially his early instruments, generally followed a Stradivari model. The violin was duly authenticated in London as a genuine Pressenda and sold handsomely at a Sotheby’s auction.

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Tweet

Replies

Very cool!

Fascinating!

Full agreement with Tom, Christian and Jean!

Thank you so much for this Michael, absolutely fascinating.

My father was a Fryling pupil in Nairobi (and was later head of strings at the Conservatoire) and always spoke of him in the most glowing terms.

This is such an interesting story! Thank you for sharing it! I have many Kenyan connections and emotional ties so this story gave me another heart string to treasure.

I appreciate all the positive comments. Thank you.

Enrico, I was aware of your father's connection with Fryling in Kenya. The work you have done with the National Youth String Orchestra in the UK, mentioned in the article, is a notable continuation of this legacy, not to mention the many charity concerts you have organized.

Marcy, I'm glad the story kindled meaningful connection with Kenyan memories.

A word of thanks to Laurie and violinist.com for posting the story and saving this history from being lost to the sands of time.

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

July 17, 2024 at 10:02 PM · Thanks so much for sharing this very interesting story!