We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Kreisleriana: Fritz Kreisler Rediscovered, Part 2: Bach Mozart and Beethoven Reductions

The great Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) performed many violin-piano recitals in which he played concertos or pieces written for orchestral accompaniment, or for another instrumentations entirely. Such was the style of the time.

For example, Kreisler made arrangement/reductions of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto and the first movement of the Paganini First Concerto that were published, but are now out of print. (I will speak more about this in the fourth part of my series.)

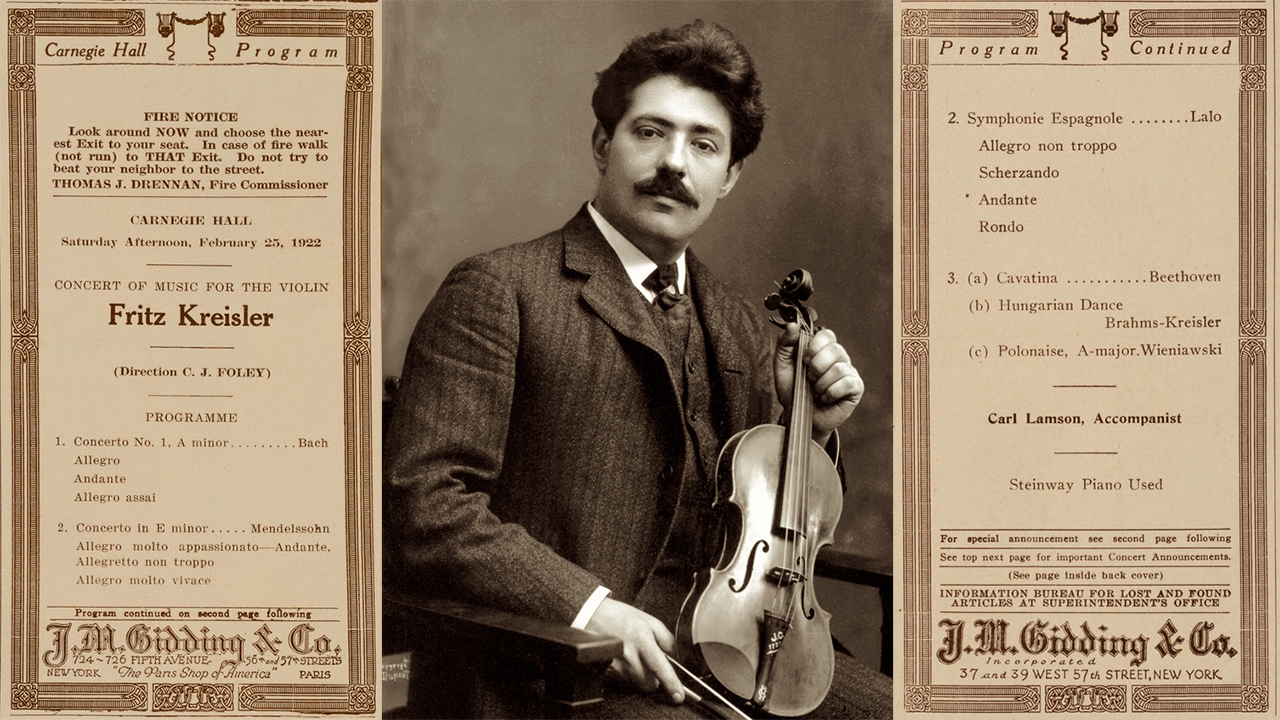

Violinist Fritz Kreisler and a Carnegie Hall program from 1922.

There were plenty of other pieces that Kreisler revised and forced his pianist to play. For this article, I will talk about two concerto reductions used for my own recital - Bach's Concerto in A minor and Mozart Violin Concerto No 3 in G major - where my collaborator, pianist Michelle Kim, does her best impression of an orchestra. I'll also talk about a quartet arrangement, the "Cavatina" from Beethoven's Quartet No. 13 in B flat major, Op. 130, also arranged by Kreisler for piano and violin.

Violinist Darwin Shen and pianist Michelle Kim, in recital on February 23, 2025 at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Westport, Conn.

It is strange to think that the Bach concerti and the Mozart concerti could ever have fallen out of fashion, but at the time of Kreisler's early career, such pieces represented a different time with different sensibilities.

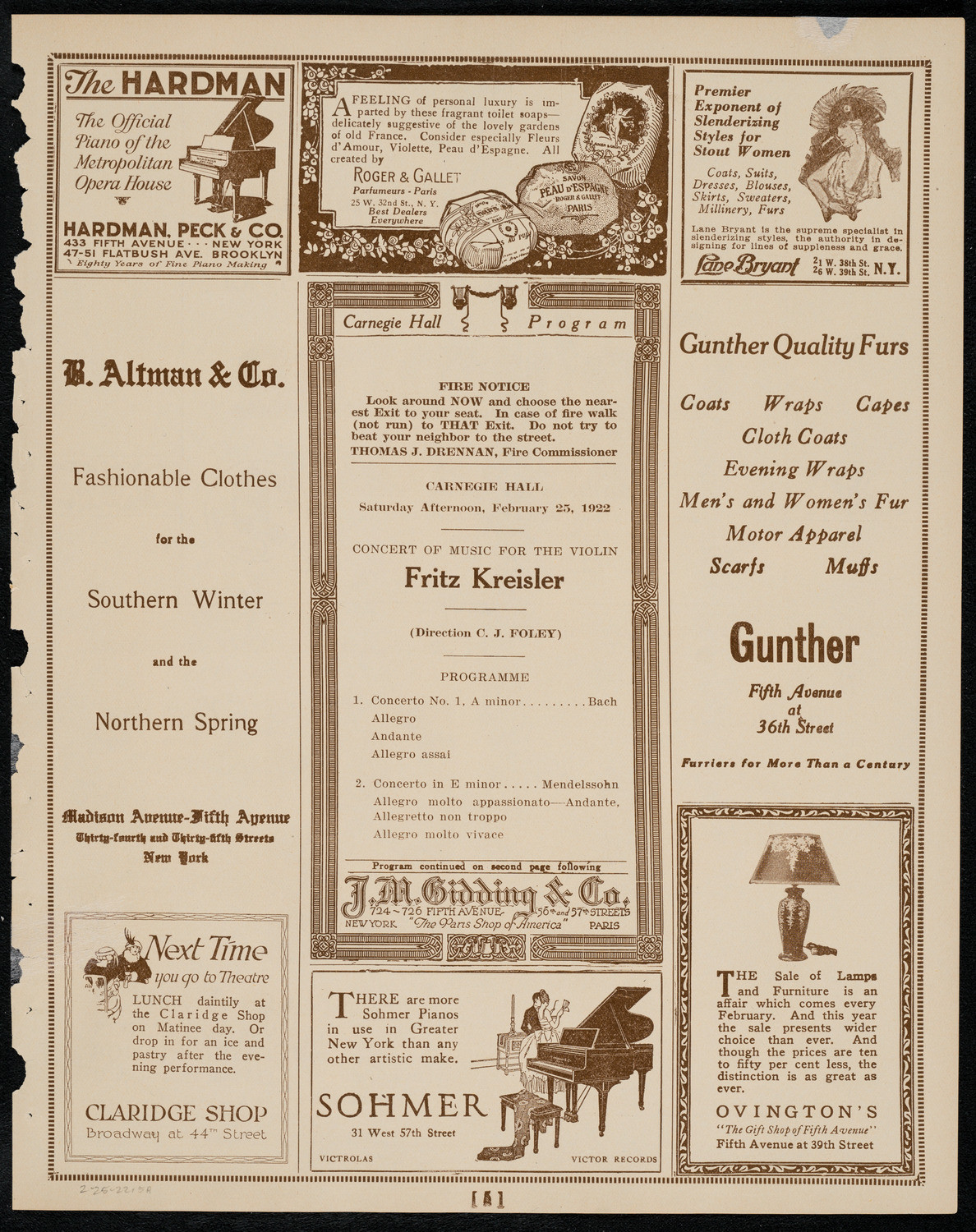

Carnegie hall February 25, 1922

Kreisler understood the greatness of Bach's violin music, and he had championed the unaccompanied works. One of the coolest videos on Youtube is this one: the Bach "Adagio" from Bach Violin Sonata #1 as played by Arnold Rosé, Fritz Kreisler and Joseph Szigeti:

Here we can hear the non-vibrato performance of Arnold Rosé, the lush continuous vibrato of Kreisler and then the performance of Joseph Szigeti, in which it which sounds like vibrato is now here to stay.

Kreisler, along with the Russian-American violinist Efrem Zimbalist, actually made the first recording of the Bach Double Concerto. According to Roy Malan’s biography Efrem Zimbalist: A Life, each soloist wanted to be Violin 2 rather than Violin 1. One cheeky student asked Zimbalist about the glorious Kreisler sound, and Zimbalist responded, "When one stood very close to him one might think the tone a trifle harsh - he used mostly the middle of the bow and pressed - one could hear the friction. But from the first row back, it was the heavenly, ringing sound."

J.S. Bach's Violin Concerto in A Minor

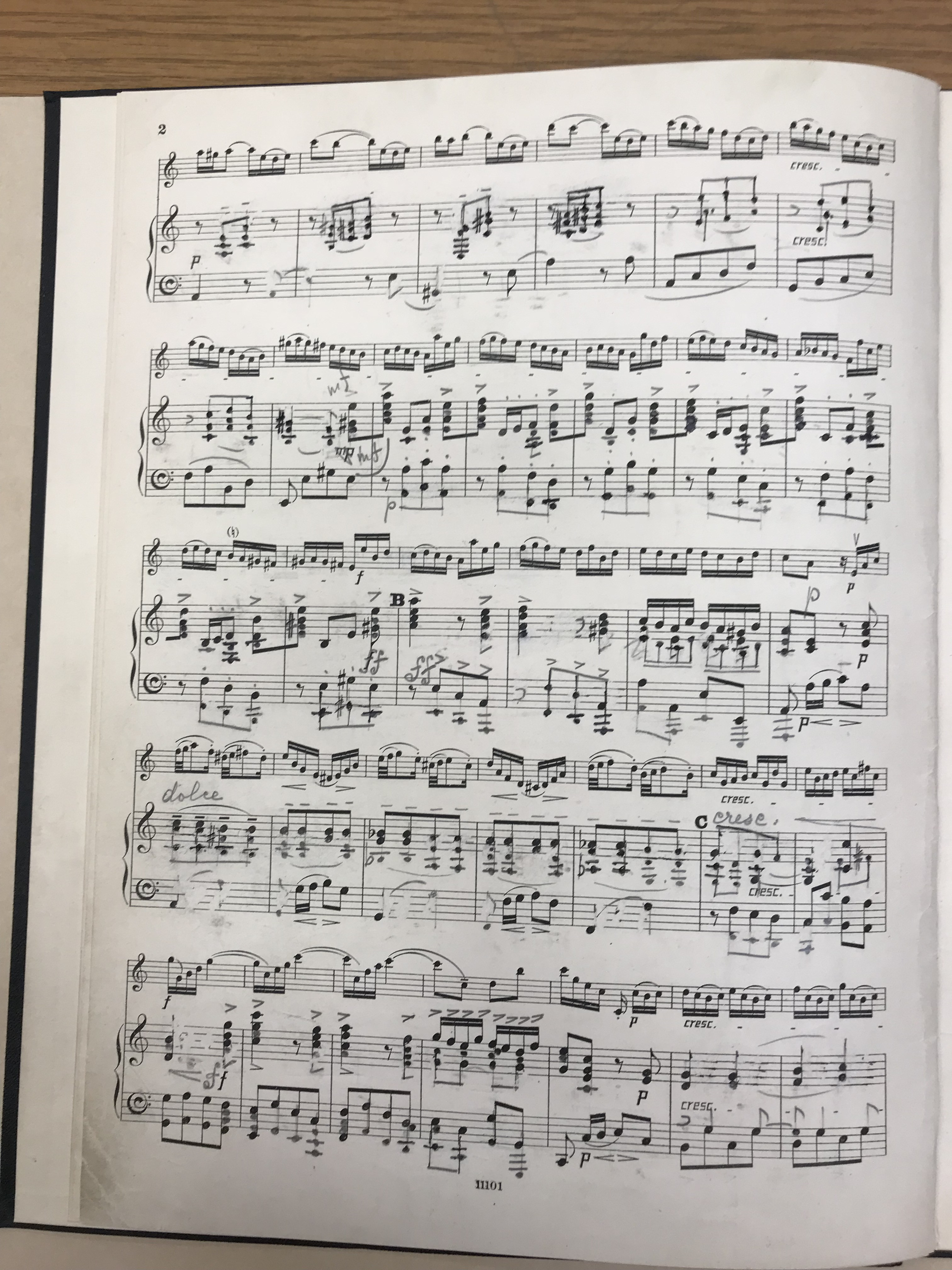

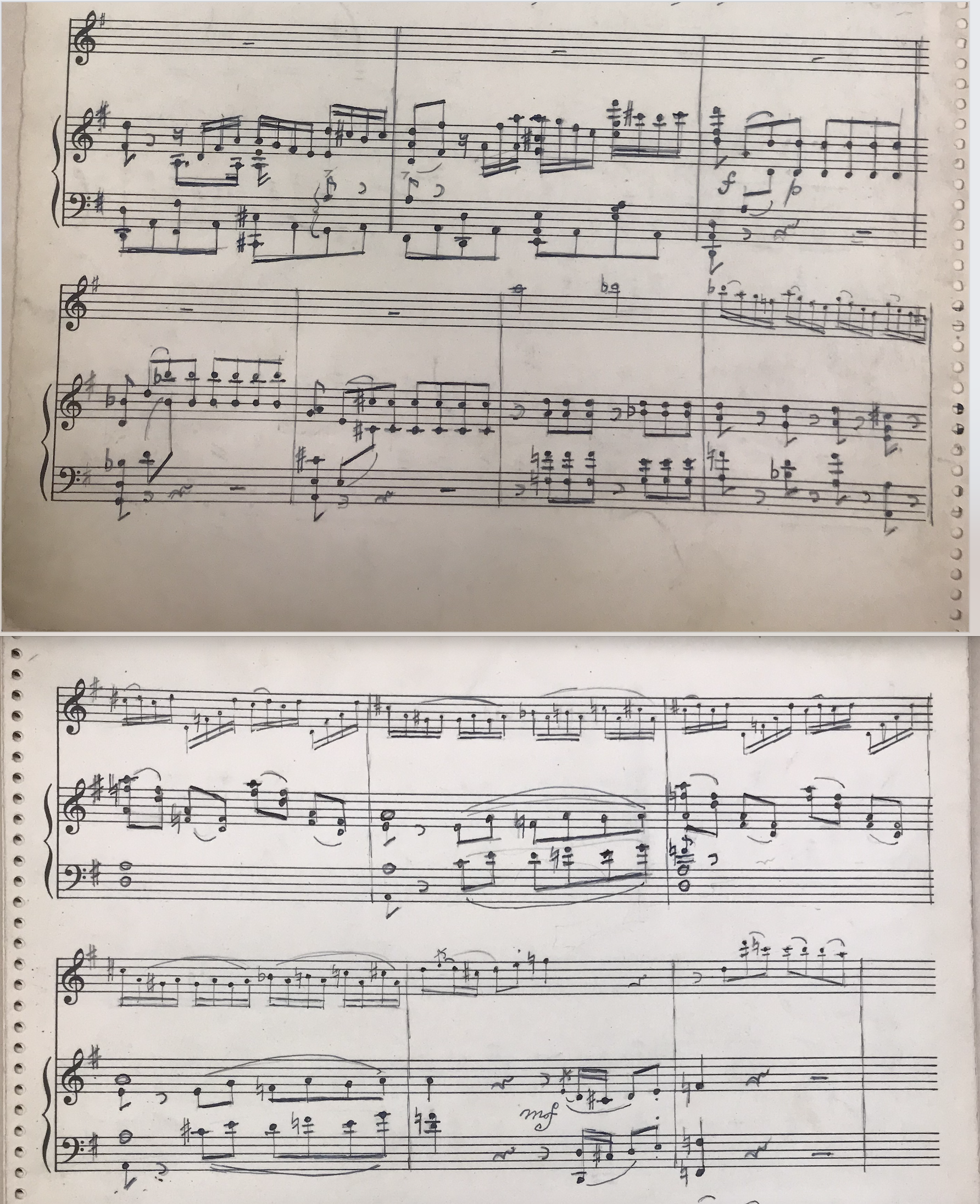

In his reduction of the A minor Violin Concerto by Bach, Kreisler makes the piano part much denser than what we would be accustomed to in a modern reduction, and he also reinforces the bass part. He changes nothing in the violin part, opting to mark up the printed score rather than write out a completely new part.

Rather than write out a completely new part like he does with other concerto, he takes the Wilhelmj edition and marks it very thoroughly. At least he’s neat!

For our recital, Michelle played the piano reduction wonderfully but tried to lower her volume so as not to overpower me. I don’t think she had much to worry about!

W.A. Mozart's Violin Concerto No 3 in G major

Kreisler never commercially recorded the third violin concerto, only the fourth. But we are lucky enough to have a live recording of Kreisler playing this at the tail end of his glorious career.

Recorded for the Bell Telephone Hour in 1950, when the violinist was now suffering some insecurity in the higher registers due to hearing loss, he does well, especially in the fiendishly difficult cadenza.

Those of you out there who ask for the sheet music, I am unfortunately not at liberty to share, but in this case, someone else has published the cadenza:

https://vladimirdyo.gumroad.com/l/mozart3cadenzas

At the time, it was not unusual for performers to alter the violin parts of concerti. Think about the Vivaldi A minor concerto from the Suzuki Book 4, which is the edition by Tivadar Nachez. Such changes were far from out of the ordinary, they were the norm. So it is, when students of mine download a concerto from IMSLP they are sometimes shocked to find different notes or a change in range. But this is not surprising.

In the case of Mozart's Concerto No. 3, for some reason Kreisler decides to cut a couple of repeated measures in the minor section, as if this repeat is just too much.

Once again, the piano part is denser but at times the violin is asked to join the piano during the tuttis. When we reach the cadenza, we find something of quite extraordinary difficulty. It reminds me of the tremolos in the oft-played Beethoven violin concerto cadenzas. Is it hard? Yup. I’m not the strongest violin player these days but certainly Kreisler didn’t take any short cuts.

Beethoven's "Cavatina" from Quartet No. 13 in B flat major, Op. 130

The last piece I'd like to describe is by Beethoven. I performed this with some trepidation, asking my friends a simple question:

"If you found out there was an arrangement of a famous movement from a late Beethoven string quartet for violin and piano, would you be offended? The arrangement was done by a famous violinist, though I find it beautiful I am moderately concerned whether I should publish the performance....”

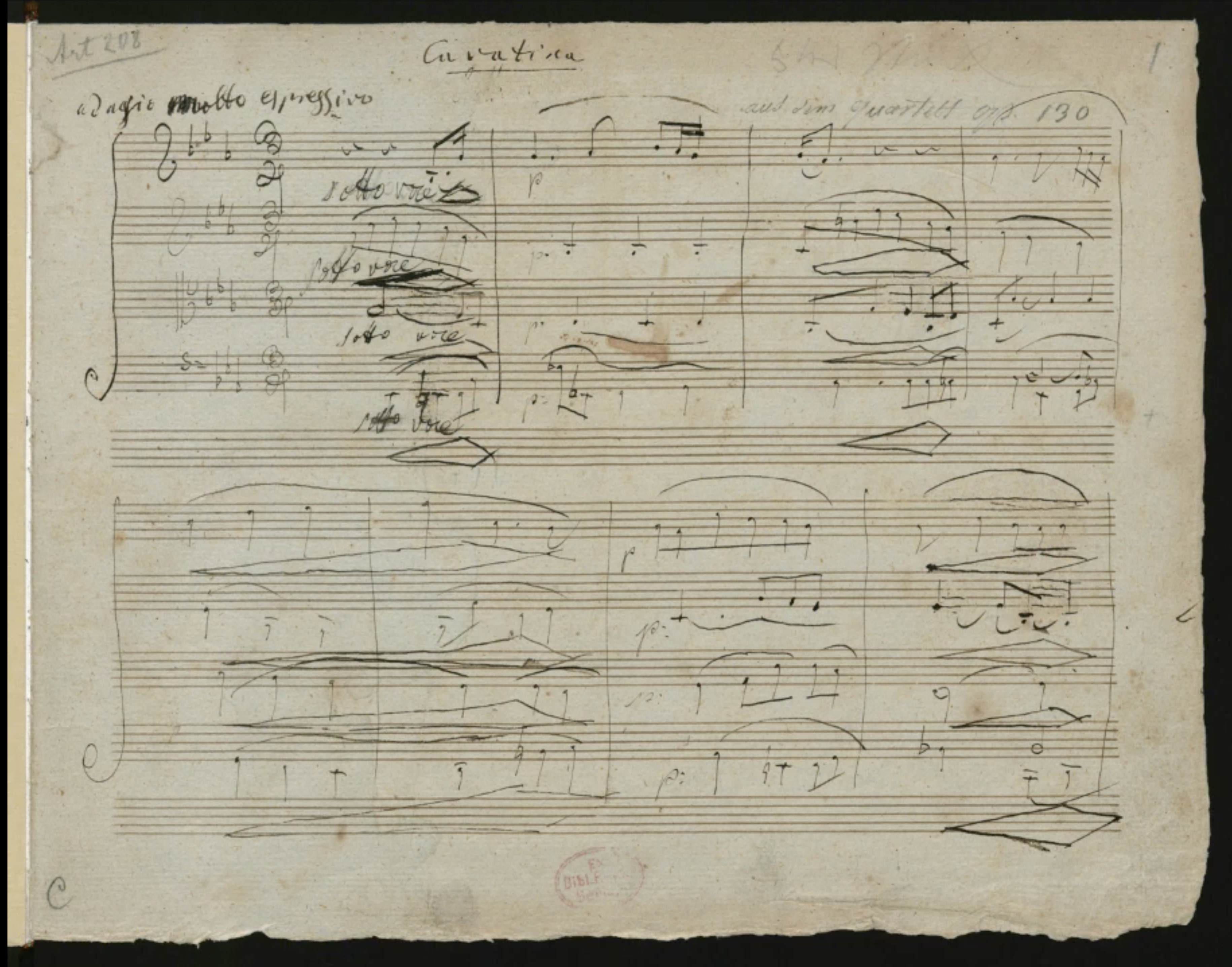

One wrote me back and said he half-expected Grosse Fugue! In this case, Kreisler decided to arrange the "Cavatina" from Beethoven's string Quartet No. 13 in B flat major, Op. 130.

We know that Kreisler played in string quartets, and indeed one of his most serious works is his own string quartet. I don’t know if he performed it much, as the score seems quite clean. But he wrote out a solo violin part, as if getting it ready for the engraver.

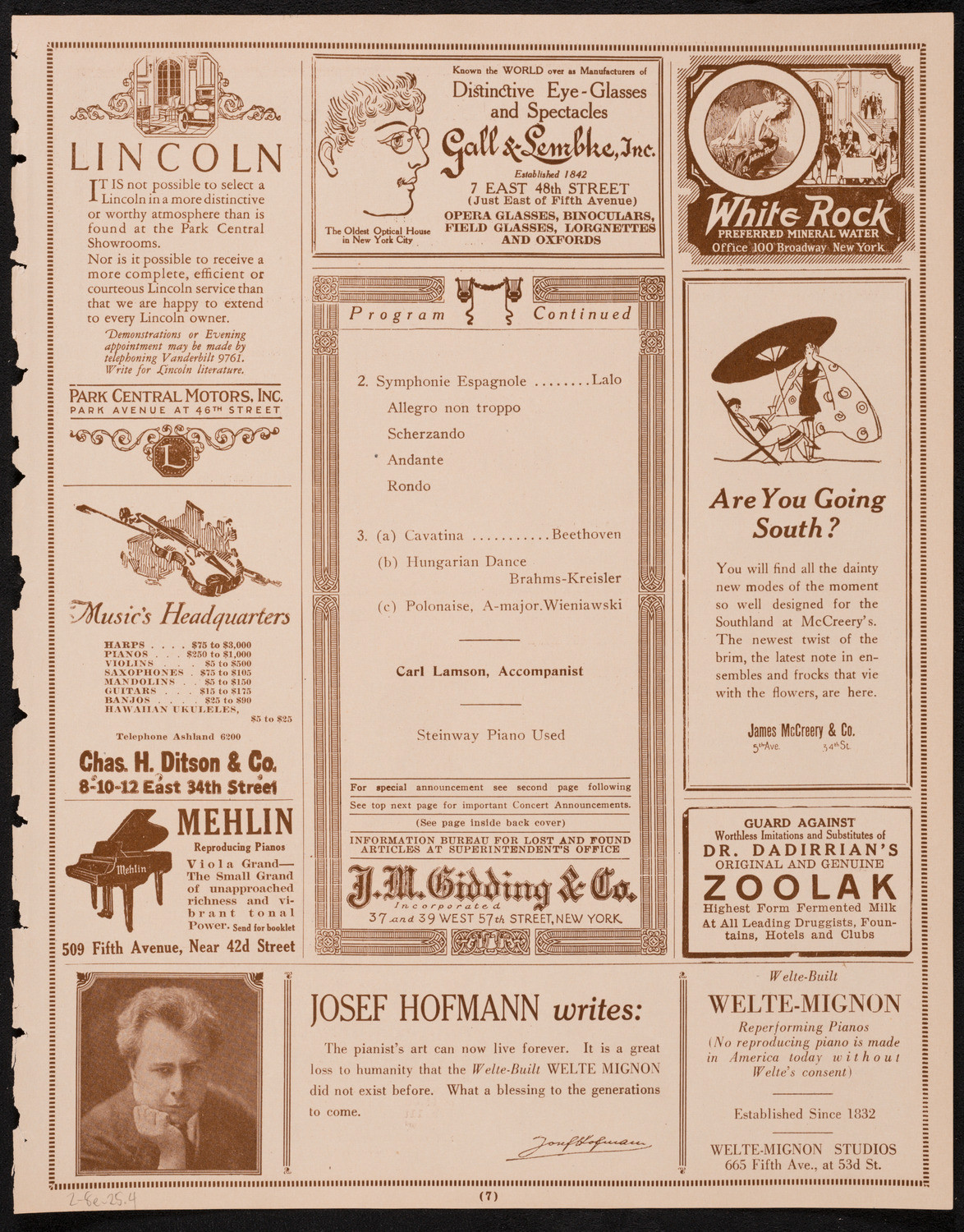

Carnegie Hall program February 9 1922 (gotta love the Carnegie Hall Digital Archives)

"For (Beethoven) the crowning achievement of his quartet writing, and his favorite piece, was the E-Flat 'Cavatina' in 3/4 time from the Quartet in B flat major Op. 130. He actually composed it in tears of melancholy (during the summer of 1825) and confessed to me that his own music had never had such an effect on him before, and that even thinking back to that piece cost him fresh tears." These are the words of Beethoven's secretary, the violinist Karl Holz.

If you haven’t seen Beethoven’s handwriting you really should. It’s at times simple, at other times angry, and at all times the hand of a genius.

In performing this, I knew that I faced not only possible criticism on tampering with a great work, but also the issue of how this would translate from strings to piano. I thought about this as a matter of speed. Most modern performances are slower; however, Beethoven himself had pretty ridiculously fast metronome markings. In this case, we don’t have Beethoven’s own markings but that of his secretary, the violinist Karl Holz: 66 for an eighth note. My partner in crime, Michelle Kim, was able to sustain the parts at this speed so we went with it. Other quartets go as slow as 50 per eighth note - however, this would be impossible with a piano.

One other interesting thing about this piece is that it is the last item on the Voyager Golden Record, the phonographs included aboard the two Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977 and intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial life form who may find them. If this is the last thing that other worlds hear from our world after we are all long gone, this would be a fitting tribute to humanity. (The T-shirt I am wearing is from the Voyager space craft)

Once again, I thank the Library of Congress for letting me research, and I am indebted to Michelle Kim for her artistry, friendship, patience and musicianship in these performances. I especially thank her for lying to a middle-aged violinist and saying that his playing was good enough. After having performed it, the Cavatina did grow on both of us and I know she does the piano part justice, but I hope you will find that I do too!

You might also like:

- Kreisleriana: Fritz Kreisler Rediscovered, Part 1

- Kreisleriana: Fritz Kreisler Rediscovered, Part 3: Rachmaninoff and Korngold arrangements

- Kreisleriana: Fritz Kreisler Rediscovered, Part 4: the unpublished 1943 La Campanella

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

August 19, 2025 at 09:36 PM · in fairness, Arnold Rosé in that Bach does not really play non-vibrato. he mainly does not vibrate the double stops. the long single notes he does, but less intense and perhaps less picked up by the recording technology at the time?