We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Master Class with Juilliard Quartet First Violinist Areta Zhulla

Communicating what you want to do in a given piece of music is not always easy. Areta Zhulla - first violinist of the Juilliard String Quartet since 2018 - ought to know; she has to communicate these ideas with her colleagues, and they are constantly making musical decisions together.

"We have to use a lot of words, in order to get on the same page," Zhulla said.

But coming up with those words - it's not only helpful when working with others, it is helpful in working out your own ideas and interpretations.

Before being in the Juilliard quartet "I never did that in my solo playing," Zhulla said, but that process of honing in on exactly what you want to say musically and putting words to it - this is extremely useful. "Once you know what you are aiming for, you can figure out how to get there."

This was one of the important points that Zhulla made during a master class she gave at the Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies at The Juilliard School in June.

Zhulla earned both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Juilliard, studying with Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho, and now teaches on the faculty. She is a third-generation violinist of Greek descent, and one of her early teachers was her father, the luthier Lefter Zhulla.

During the master class, Zhulla taught with humor and persistence, emphasizing expression and connecting with the audience.

Audience connection was a central point she highlighted with the first student artist, Keila Wakao, who performed the "Presto" from Beethoven's Sonata No. 4 in A minor, Op. 23 with pianist Evan Solomon. Wakao's performance was expressive and beautiful. Beethoven does not play itself, and Keila really put a lot into it.

"You capture so much of the spirit of this piece and you had so much individuality," Zhulla told her. But how does one project that message to the audience?

"Do you ever think of the audience in a territorial way?" Zhulla asked, with a sly smile. "I like to look at the last person, in the very back," Zhulla said.

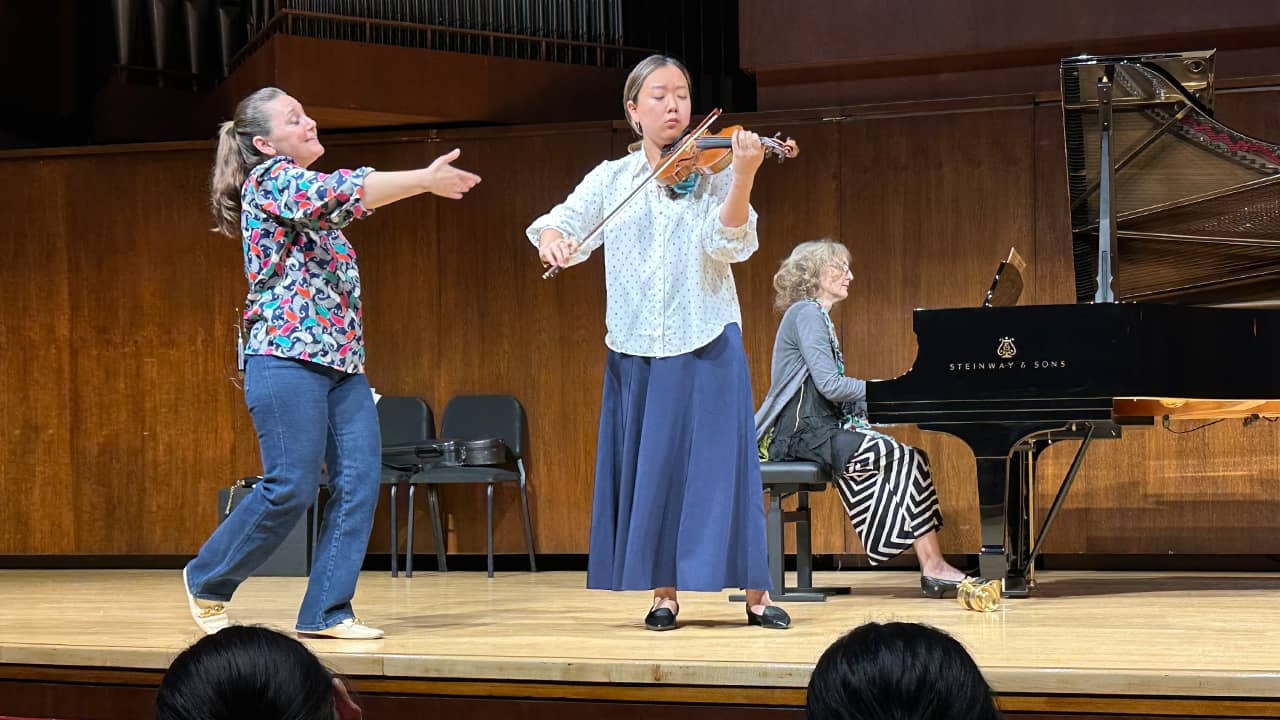

Areta Zhulla with student artist Keila Wakao. Photo by Violinist.com.

Pointing to an audience member in the back row, Zhulla said, "I'm going to play for you!" then she smiled made a little heart with her hands.

Of course, it helps to have that intention of projecting to the back row, but how does one actually do it?

One way involves thinking of dynamics as atmosphere, rather than something literal. All of the musical emotions exist in a forte setting, and they all exist in a piano setting, Zhulla said. "You can be angry in forte, you can be angry in piano," she said. The volume - or lack of it - should neither drown out or mute your expression.

She also emphasized stature - if you are leaning forward, there is a feeling of holding things inward. Instead, stack yourself up: knees over ankles, and on top of that is your hips, your abs, your shoulders. Feel gravity and project outward.

Zhulla said to "live every note with us," and she suggested developing a broader vocabulary for expression. She cited Karen Tuttle's compendium of words for human emotions, where she takes five human emotions - love, joy, anger, fear and sorrow - and provides 40+ words that illuminate "sub-characters" of those emotions.

Blues Zhang next performed the third-movement "Andante sostenuto" from Bruch's "Scottish Fantasy" with pianist Jinhee Park. It's a beautiful slow movement, which he played with nicely effective vibrato and a rich and pure sound - it was quite spellbinding.

Zhulla brought up the idea of creating a melody line that would soar above the orchestra, but doing so in a relaxed way - except she didn't exactly want to use the word "relaxed," when it comes to performing.

"I don't relate to someone telling me to 'relax' - I'm working!" Zhulla said. "But I can 'not send tension.'"

For example, when there is a big shift in the left hand, sometimes the mental tension actually comes out in the bow. "The bow hand doesn't have to worry about it - but it still does!" she said. If you can instead find comfort and freedom in the right arm, that can help alleviate stress of something going on in the left hand.

She advised against trying to control the left hand with your eyes - "you can't" she said. "We play it by braille." You don't even need a mirror; just feel the sound you want.

She wanted him to use the bow to "catch some depth to grow your sound," she said, "mold the phrase all the way to the end, don't just let it go."

Areta Zhulla with student artist Blues Zhang. Photo by Violinist.com.

One has to be especially expressive in soft passages.

"The lower dynamics are the most dangerous," Zhulla said. "The road you are walking on - the area where you are carrying the tone - just became tiny. But that does not mean we will give up our intentions."

Next Josh Liu performed two works, with two violins and bows: the first-movement Adagio from Bach's G minor Sonata; and Caprice No. 6 by Paganini.

For the Bach he had a Baroque set-up - including a Baroque bow, and (if I'm not mistaken!) a lower tuning and perhaps even gut strings. His interpretation also leaned toward historical practices, compressing decorations, using limited vibrato, and even a few intentional deviations from notes we customarily play (an E natural in m.3 - later he told me that he'd decided on this note from examining the manuscript.)

The Baroque bow seemed to present some challenges - it has a different balance than a modern bow, and here was a tendency to press more than needed.

Zhulla told him that "sustaining is not necessarily the option you want to go for," using these Baroque tools. She wanted him to find the "release point" in the bow, and "everything you do, needs to happen before that release point."

This suggestion helped him a great deal, and as he worked to balance the bow more toward its lower half, the long phrase he'd been trying to create really came off clearly.

Areta Zhulla with student artist Josh Liu. Photo by Violinist.com.

"I loved the way you organized your sound," she said.

For Paganini Caprice No. 6, Josh used a modern bow and violin set-up. For this, the sound was very quiet in the beginning. As he went through the piece, the trills were a bit fluttery and muted.

She commended his strong sense of pulse, then encouraged him to think in terms of events that happen in the piece, to try to get the audience to relate to the pulse. She wanted him to show the flow, the direction, the event.

She also talked about how to make the double stops work - "the contact point that they require is so specific," she said. A minimal adjustment of more friction with the bow also would help clarify those notes "so that the audience can get all the information."

She kept encouraging him to "make the contact point more specific," and to "put it in context, of what you just played and what's coming up."

This really worked well - a little tweaking made a big difference. I enjoyed this teacher-student interaction - very effective!

After this performance, Natalie Oh played Tchaikovsky's "Melodie," showing really fluid movements and playing with a beautiful posture, and the performance seemed to become more comfortable as she went along.

Afterwards, Zhulla had her start the piece again, and indeed the beginning sounded more open, with a looser and more natural vibrato.

Zhulla asked the question - which applies to so many of us, "How can we get into that state of ease?"

She quoted the great violinist Itzhak Perlman (who was one of her teachers), who customarily asked the question, "Why don't you play it the first time, like you played it the second time?" It's not easy to achieve that ease, the second we walk on stage, but that is our aim. Zhulla asked Natalie what she was thinking about, when walking onto stage, and Natalie said that she felt vulnerable.

"Vulnerable is good," Zhulla said. That feeling can make us feel nervous or scared, but allowing some vulnerability is also something that makes us good performers. "Without it, we couldn't do this."

Zhulla assured Natalie that she is not the only person who has walked out on stage feeling this way; "other people have thought those thoughts." When you walk out on stage to perform, it means you about to show people something, to let them into an emotional world; feelings of vulnerability make sense in this context. But how to you put those feelings in their place?

She described a few techniques: Telling your inner voice, "thank you for sharing," and then setting that aside and breathing. Or, looking around and realizing - "look, it's people, people just like me!"

Areta Zhulla with student artist Natalie Oh. Photo by Violinist.com.

Also, keep in mind that the audience wants you to succeed; and likewise you want to welcome them into your world. After that, focus on interpretation.

"There is comfort in technique, but put it away, and let's focus on interpretation," Zhulla said. She talked about a few specific things in the music: focusing on freedom in the bow arm, using different emotions in the steps of a crescendo, and in a spot where there were repetitions - "are you creating a little tornado there?"

Next, Anthony Dorsey performed the first movement from the Concerto in G minor, Op. 80, by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, with pianist Jinhee Park. This is a piece I have not heard much before - it's a little bluesy, with a lot of rising patterns and trills, and also a lot of octaves, which Anthony played very nicely.

"It felt like it flew by," Zhulla said after his performance, "you were so in the flow."

Areta Zhulla with student artist Anthony Dorsey. Photo by Violinist.com.

Much of the piece is "forte," and Zhulla wanted to look at different ways of playing loud.

"If I don't identify what kind of forte I'm playing," she said, "they all end up sounding serious."

Titles that are written can help with this. The beginning is marked "Allegro maestoso" - fast and majestic - "What does that mean to you?" she asked him.

He said it feels like a march, played with projection, openness.

"As the fortes keep coming back, ask yourself what kind of forte this is," she said.

The next forte was "Vivace." That means lively, "with a spring in your step." She walked across the stage, with a spring in her step. The music has to have that feeling of a spring in the sound.

Last was Lauren Yoon, who played the third movement of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, with Evan Solomon playing piano. She played with a lot of power (resulting in a lot of broken bow strings!). It was a committed performance with a lot of energy and even the occasional smile.

Zhulla praised her joyous energy, and encouraged her to make it also sound more mischievous, like "I'm up to something..."

Then they worked on one of the biggest techniques in this movement: spiccato. Zhulla also wanted to hear more of the "tinies" - the many fast bouncing notes. Certainly, Lauren was getting them to bounce, but Zhulla wanted to refine that, to give it more direction, variety, precision and dynamics.

Taking Lauren's bow, Zhulla tightened it and gave it some more rosin. The bow should grip the string a bit more, rather than just letting it go.

Areta Zhulla with student artist Lauren Yoon. Photo by Violinist.com.

"The bounce point is lower than what you were doing," she said, meaning more toward the frog. "Find the spot where it bounces, and the lower it."

She was aiming to bring her to a different mode of synchronicity between the two hands - not so much so hear the notes better but "to hear the energy, that is, the playfulness."

"If you are thinking back and forth (with the bow), then you are at the mercy of your bow, whether it will bounce or not," Zhulla said. "If you think in circles, you are making your bow bounce."

You might also like:

- Katie Lansdale: Irresistible Violin Repertoire from Around the Globe

- Master Class with Philip Setzer

- All stories from Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies at Juilliard

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

I haven’t heard Josh’s argument for the E natural in bar 3, but I think everything we see in the manuscript and copies is consistent with old JS making a mistake, too. Remember that the practice of the time was that accidentals applied only to the note where they were written, and he repeats them over and over. The rest of bar 3 would be unchanged if he intended the modern interpretation and simply omitted that first E-flat.

It isn’t proof, I agree. But isn’t this piece supposed to be in G minor? He didn’t even write the correct key signature! Writing with the proper key signature, that note would not need an explicit accidental, and elsewhere he lets the key signature do the work. I have seen an edition or two that put in the missing E-flat in the key signature.

And look at the manuscript for bar 2 — the note after the rest looks an awful lot like an F, not a G. It doesn’t sound any more wrong to me than the E missing its flat in bar 3. YMMV.

Sorry Bill, but I disagree with your suggestion that E-natural is JSB's "mistake". First: I do agree that whatever you meant in your first paragraph was not a proof of anything. Second: of course the piece is in G-minor, but for whatever reason JSB decided to have one flat only in his key signature and he consistently followed that throughout the entire four movements of the Sonata, adding Eb every time it is needed which is a lot considering that, as you correctly pointed out, accidentals only applied to the note next to which they were written (except in cases of repeated notes, even when they are separated by a bar-line). Third: inside of the very first measure there are already two E-naturals in the fourth beat and we do not question either one of them because they sound perfectly fine in this descending-ascending G-minor line. Same is true for many more E-naturals in the Adagio such as in measures 5 through 8 and in the penultimate measure as well. Fourth: I don't see any reason not to conclude that he "lets the key signature do the work" not just "elsewhere" but everywhere in this piece. Fifth: the note after the rest in measure 2 looks to me very much like G because its bottom is clearly above the first line without touching it and its top is clearly sticking out above the second line. If you look carefully at all of the Fs in the same octave before and after, you will see that all of them are located solidly between first and second lines covering the entire area between them but not sticking out either below first or above second. So there is no doubt that the note in question is a G. As for the fact that the E-natural (in harmony) in the third measure is followed almost immediately by Eb (in melody) in a different octave, that does not prove anything in JSB's music either because, for example, in measure 16 a B-natural is followed almost immediately by Bb - both in melody and in the same octave.

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

July 27, 2025 at 05:44 PM · This is an inspiring account of a violin master class! Reading it tells me to cultivate an overall spirit of exploring the widest range of expression and technique in making music as intentionally as possible. Finally just last month I participated in 2 weeks of daily master classes at Oberlin Baroque, and this article brought me back to the thrill of witnessing a few revered (by me) baroque violinists give deep and spontaneous critiques and coachings to students playing much better than I can so far --and I continue to work on the exact advice I got when I played in those classes.

Especially serendipitous for me in this article is to read of Juilliard student Josh Liu's participation in the master class. Personally I never think of him as a student because I've heard him play with diverse passions and stunning virtuosity when he was on the Sprague Hall stage at Yale. I was privileged to take about 6 months lessons in baroque violin from Josh, and it has changed me. I have no doubt his baroque playing continues to be authentic not just in technique and in close reading of original scores, but also in gut strings and overall set up and tuning.