Master Class with Donald Weilerstein - Starling-DeLay 2025

It's one thing to play softly, but there is an art to projecting the feeling of intimacy out to a concert hall.

This is one of the concepts that violinist Donald Weilerstein discussed on the third day of the Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies. Weilerstein earned his bachelor's and master's degrees at Juilliard in the 1960s, played for 20 years in the Cleveland Quartet and has served on the Juilliard faculty since 2000.

He also talked about posture and sound production, offering concepts of balance and energy grounded in practices such as tai chi and yoga. Those concepts can get a bit esoteric, even seeming a little off-topic. But let's not forget: violin playing is both a physical pursuit and a practice that requires uncommon devotion. In that context, we certainly can use some sound body-mind advice, and Weilerstein, at age 85, has been honing his message for many years!

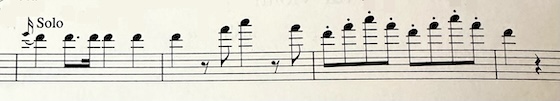

Weilerstein's ideas about projecting intimacy were in response to the day's first performance, by student artist Josh Liu, who played the first movement of Bernstein's "Serenade, after Plato's Symposium." Liu, a master's student at Yale University, played the very exposed opening to this movement with excellent control, with a good mix of vibrato and non-vibrato. He also not only hit the insanely high A but also applied vibrato here. (Symposium Artistic Director Brian Lewis had spoken of that note in his pedagogy class the day before, commenting that it's so high, "it's actually here..." reaching all the way behind his head!) The movement eventually evolves into an elegant dance, and here the music started feeling a little internal - or to say it more simply, too quiet to let the audience in.

Weilerstein addressed this by going straight to the fundamentals: he had Josh play a scale, then asked him where he felt the sound. The answer: his chest. Weilerstein wanted him to think more like an opera singer, to strive to feel it all lower in the abdomen.

Donald Weilerstein with student artist Josh Liu.

He then talked about the fundamentals of producing a sound, bow to string. On the down bow, the bow begins from the right side of the string (as you look down your fingerboard), then goes through the string, to the left side of the string.

"Scoop that very deep," Weilerstein said, as Josh played an open G string.

He talked about activating muscles in the back, the lats, while bowing. They tried this without the violin or bow, slowly flapping their arms backwards, thinking of doing a back-stroke, swimming.

At this point, I began to wonder if we were really going to circle back to Bernstein at any point... But hang on, we did...

Doing the down bow, he said to catch the string enough to "feel like you are pulling the string a tiny bit to the right."

"Singers sing through their back," he said; likewise, when it comes to producing a note on the violin, "feel it through your whole body."

Producing an up-bow stroke, the bow begins by engaging from the left side of the string, then going "through" the string and to the right side.

Liu played a scale, with Weilerstein encouraging him to feel the sound very deeply, to feel the sound from the front of the body to the back.

At this point, we began to return to Bernstein, to a slow passage had come across a little too quietly.

"It is 'mezzo voce,' that is true," Weilerstein said. ("mezzo voce"="half-voice") However, that doesn't mean playing it backing off to the point of masking the sound. He had a little secret for creating a sense of "mezzo voce" in a hall: "You can project the feeling of intimacy if you aim your sound toward the right side of the hall," he said. And by "right side," he meant their right side, as they stood on stage and faced the audience.

He had Josh point the f holes toward the right, then told him to also listen out of his right ear, "as if you have a beam of sound going out into the hall and back to you. Keep aiming the sound all the time."

Remarkably, this really did work - it was possible to hear everything Josh was playing, yet it had that sense of being quietly delivered.

They then worked on the faster part, and Weilerstein instructed him to think of "scooping" through the fast notes, and be sure to scoop on the right side (the up-bows). This encouraged a very active bow stroke that really brought out the clarity of the passage.

Next Lauren Yoon, a Juilliard Pre-College student from South Korea, performed the "Fuga" from Bach's solo Sonata in G minor. Playing with her eyes closed, she executed the tricky chords and double-stops very well, also delineating the fugue's multiple voices, putting the chords on the beat rather than using "rebound" chords to get bak to the main voice. The teacher in me also noticed that she had a strong and active pinkie on the bow stick!

Weilerstein began by asking her, "What elements of the music do you use, to reach your audience?" She said, "How I feel."

He acknowledged that instinct is good, but what are the elements of music? She mentioned embellishment, dynamics, but he was trying to get to elements like melody, rhythm, harmony...

Weilerstein switched gears: "Theory is only interesting for me if I do it instinctually," he said.

Using her violin, he played the beginning of the piece, pointing out the dissonant chords made by the two voices...

"What is this?" he asked. She wasn't sure how to answer, so he stopped trying to get the word "dissonant" out of her and asked, "How does that sound make you feel?"

"Like a trap," she said.

"There is a struggle in it," he acknowledged. "You want to get out of that struggle." Dissonance wants to move to consonance.

She played it again, without being much affected by the dissonance.

"If you are in a trap, you don't want to play it like that!" he said. It was too content, "you have to not enjoy it."

Donald Weilerstein with student artist Lauren Yoon.

"Like it suffers," he continued.

Without a trace of impatience, he persisted in trying to get her to feel the conflict and clash of the dissonance, and to convey that as a performer.

"It's like you are telling a musical story," he said, "you want those notes to squeeze against each other."

He explained, there are actually several kinds of dissonances - the dark dissonances, which are all about suffering. And then there are the dissonances, as in V7 chords, that are anticipatory - they make you anticipate the resolution.

"It's really an emotional instinct story," he said.

She did, in the end, start bringing out more of the dissonances. By the end, he said sincerely "You felt all those harmonies well."

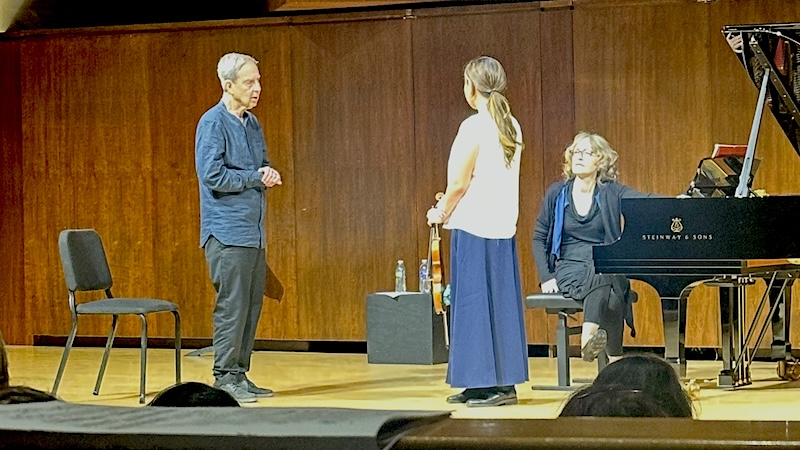

Next Ellie Sievers performed the first movement of Mozart's Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major. Ellie produced a sparkly sound and good collaborative spirit with pianist Pamela Viktoria Pyle. She also played her own cadenza, which had some fun and creative harmonic moments.

Donald Weilerstein with student artist Ellie Sievers.

When she finished, Weilerstein asked her how she listens to herself, in terms of projection.

She said, "I try to think about making things not too fast, so that they can be heard," she said. (Some good wisdom there - sometimes the notes sound better when they are slightly slower because they are audible to the listener..)

She also said that she thought about "projecting past the back row."

Weilerstein wanted her to tweak that idea: "Think of bouncing the sound off the back wall, and back to you," he said. He encouraged her to listen with the right (rather than left) ear, to hear that sound coming back to her.

Ellie also told him that she thinks of opera when playing Mozart, and he said that she could make it more operatic if she put words to exactly what kind of drama she was creating. For example, the beginning: "if it had to be an opera, what character would it be?"

"A hero?" Ellie ventured.

"Yes!" he said, then throughout the rest of the time he used Ellie's word as he worked with her. He told her to play the opening triad figure in a way that feels and sounds heroic.

He asked her to imagine feeling like a hero, and embracing that feeling, almost like an actor.

He talked more about the eighth-note triads: "A lot happens if you listen between the notes," he said. He told her to bounce those eighth notes off the back wall, and listen for the reverberation in between.

He encouraged her to "be moved by the harmony" when playing those notes and to shift the weight of the fingers, 1-3-4-3-1-3-4-3-1.

They also worked on playing some of the slurred eighths, in rhythms, separately and staccato, and with a semi-portato.

He was impressed that she had written her own cadenza - so was I!

Next came a Bach Sonata - not one of the solo sonatas but one originally written for violin and harpsichord, the Sonata No. 4 in C minor, BWV 1017. Claire Arias-Kim played the first two movements with pianist Pamela Viktoria Pyle. This was a very beautiful, modern take on the music, played on a modern violin and Steinway piano.

Donald Weilerstein with student artist Claire Arias-Kim.

Weilerstein said that he felt that Claire was hearing the harmony very well and asked what she thought of it from a rhythmical perspective. She responded that it felt like a dance, and he said that she could play off of this more.

At this point he asked how he could be of most help, and she said that she wanted to work on how she was physically feeling the music, to expand the feeling from being limited to the upper body to feeling the sound more from the stomach.

She played a scale for him and he said that "most people say not to move, but you can move more."

"If you sing music all the way through the body, you become the music," he said. Playing that way "takes the ego way from it, for me. It helps to envision 'I am the music.'"

Weilerstein said that it is possible to feel the vibration of the music in your body, even down to your bones. You can put your hands on your hips and feel the bones moving in the sockets of the pelvis. "You feel a swing in the hip joint," he said.

When performing, "I imagine myself as large as the room," Weilerstein said. He said to imagine the spine going in two directions: to feel the arch of the spine going down through the tailbone, and up through the neck.

He also talked about the face, jaw and head - he had her smile, to try to feel the bones in the temple, jaw and cheeks. "Put the violin under your jaw and smile," he said. "Feel rubbery in the face, and let it move with the violin."

He said to breathe into the spine and tailbone, feel like you are breathing up through the knees.

The next performer was Natalie Oh, who played the first movement of Vieuxtemps' Concerto No. 5 in A minor with pianist Pamela Viktoria Pyle. Natalie played with a solid and pure sound and strong, fast vibrato.

Donald Weilerstein with student artist Natalie Oh.

Weilerstein focused on shifts, introducing the idea by talking about the 20th century violinist Isaac Stern.

Weilerstein asked her how she thought of the speed of a shift, and she said that she tries not to rush shifts, thinking of the note before the shift.

He told her that Stern said that "you should always shift off principal, main notes," and not necessarily the note right before the shift.

"Shift soulfully, not brilliantly," he said. "Try to find notes you can bounce off of - you don't have to think of every note."

This was a little bit hard to understand, but for example, playing an A major scale you would fit the shifts into the principal notes of the scale, for example, the opening A. I believe this was a way of simplifying shifts by thinking of them in a musical context. He had her play an A major arpeggio, and the idea was to make the entire three-octave arpeggio feel like one larger motion.

He also talked about the ancient Chinese mind-body practice of Tai Chi, and how in this practice "spine leads everything." With that in mind, one can think of the spine lengthening, before a shift, and even think of the spine leading the shift.

"Shift soulfully," Weilerstein advised, "not brilliantly."

You might also like:

- Master Class with Donald Weilerstein (2017)

- A Conversation with Violinist Itzhak Perlman

- All stories from Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies at Juilliard

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

Violinist.com is made possible by...

Violinist.com Holiday Gift Guide

Dimitri Musafia, Master Maker of Violin and Viola Cases

International Violin Competition of Indianapolis

Johnson String Instrument/Carriage House Violins

Subscribe

Laurie's Books

Discover the best of Violinist.com in these collections of editor Laurie Niles' exclusive interviews.

Violinist.com Interviews Volume 1, with introduction by Hilary Hahn

Violinist.com Interviews Volume 2, with introduction by Rachel Barton Pine

July 1, 2025 at 07:36 AM · An excellent report! I really appreciated the way Donald Weilerstein related so many aspects of violin playing to singing and dance.