We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Master Class with Joseph Lin

I started learning to play the violin just a few days before my ninth birthday. At the time, this wasn't too unusual.

But it is now!

Today I saw two nine-year-old violinists each play with a rare kind of mature sound, solid interpretation and self-assurance at today's Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies master class with Joseph Lin, former first violinist of the Juilliard Quartet who teaches violin and chamber music at Juilliard.

Student artists Ria Kang and Jayden King - who both played today - seem to be living parallel lives - she started at age four and he started at age three, and both were admitted at age seven to the Juilliard Pre-College program. What beautiful playing from these two clearly dedicated young musicians. I'll describe it in more detail below, as well as the fine performances by three other student artists - Blues Zhang, Anthony Dorsey and Keila Wakao.

Lin taught with a deliberate manner and a smile, diving deep into the details and offering his ideas with a gentle insistence.

The first performer of the day was the young Ria, who played the first movement of Mozart's Concerto No. 5 in A major. Ria played the slow introduction with beauty and poise, and then changed her energy so well as she dove into the faster "Allegro aperto" section. Her playing was decisive and full of nice dynamics. She used open strings to great effect and played the Joachim cadenza with all the right timing.

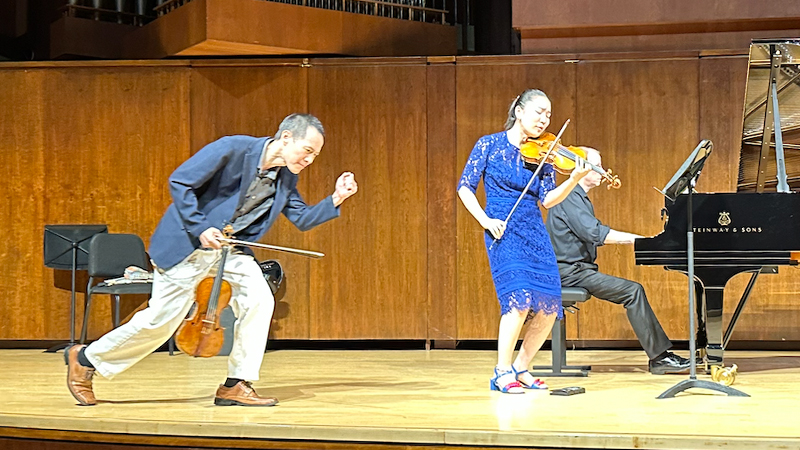

Joseph Lin and student artist Ria Kang.

After her performance, Lin asked her to describe how she feels about the piece, and with model composure she switched from playing to talking and said, "Mozart was young when he wrote this, and I think it's charming and playful. It has a lot of humor in it."

Lin said that he wanted her to connect with those ideas and demonstrate them more in her playing. He also mentioned that when playing Mozart, one is often leading the orchestra, and so one should stand in a way that conveys that. "You might be leading the orchestra, playing this," he said. "You need to communicate with the orchestra to get them to play it how you have it in your head."

Without an orchestra present, he wanted her to stand in a different place that would allow her to communicate more with the pianist, who was Jinhee Park. He had her try changing the position of her head, so she was not looking down the fingerboard but looking more forward, so she could connect more with her ears than eyes.

Next was Blues Zhang, an undergraduate student at Juilliard who has also studied at the Colburn Music Academy. He performed two movements - the third-movement Largo and the fourth-movement Allegro assai - from Bach's Sonata No. 3 in C Major. The Largo is one of the most beautiful pieces of music written for the violin, and he really made it sound gorgeous. And he gave the the Allegro assai that fast and spinning quality that makes it so appealing.

Joseph Lin and student artist Blues Zhang.

Lin focused on the Largo, and on bringing out the contrasts and counter-play in the voices that Bach manages to create in this piece for solo violin.

While we spend a lot of time, as violinists, trying to make all the registers of the instrument sound the same, "I wonder if the voices could have a more distinct quality," he said. "Allow it to be like two people singing."

Also, Lin advised him to imagine being part of the basso continuo, the part of the band that plays the foundational bass line and harmony in Baroque music. Because this line delivers the harmonic changes, it has a rhythmic role that one can explore.

Lin had Zhang play just the bass part for the first part of the Largo. After that, he had him play the top part, the melody, by itself. I was rather impressed that Zhang could do this so readily, without using any music.

Separating the parts, Lin wanted to emphasize that "you don't have to do everything with the melodic line."

In other words, "expressing more of the harmony relieves the melody from having to do all the work."

Zhang then played both voices together, and Lin literally took a step for each change in harmony, carefully walking across the stage to the very slow pace of the harmonic changes. Zhang was playing with much beauty and sensitivity that Lin simply let him play to the very end of the movement, after which we all kind of sighed. It was so good.

Next was our other very young violinist - Jayden King, who played Tchaikovsky's Valse-Scherzo Op. 34 with pianist Evan Solomon. This is a virtuoso piece with a lot of technical fireworks: double stops, fast trills, ricochet, fingered octaves... Jayden was very decisive - and impressive!

Joseph Lin and student artist Jayden King.

Lin first commented on Jayden's posture, noting that his neck was angled, holding his violin (which appeared to be a full-size.). Lin warned him not to bear down on the violin - "it's probably not good for your overall health."

Lin then had some specific suggestions to keep punching up this performance: "When doing a robust bounce of the bow, get more on the flat hairs of the bow," Lin said. "Flatter bow hairs will give you a crisper bounce."

He also wanted him to experiment with where to point the scroll, in order to deliver the best sound to the audience. Just as an experiment, he had him point the scroll straight at the audience, just to show that it can range from pointing to the sidewall, to pointing a little more toward the front, to completely forward.

Doing a big double-stop string crossing, Lin suggested that instead of catching the string, he should see if the bow could just fall from the air. He asked him to release the pressure from his neck and head on the violin in order to do all these string crossings.

Saint-Saëns Sonata No. 1 in D minor was next, played by Anthony Dorsey and pianist Jinhee Park. Dorsey is also an undergraduate at Juilliard, having previously worked with Kurt Sassmannshaus at the Starling Preparatory Strings Project at the Cincinnati College Conservatory of Music.

No one needed to tell Anthony to be engaged with the piano - he was very aware and coordinated with the piano part, and likewise he had a great partner in Jinhee Park, who was a sure partner.

Joseph Lin and student artist Anthony Dorsey.

Lin wanted to hear a greater range of color and more voicing from Anthony. To do so, Lin said "there are a variety of fingering choices we could explore" - and so they did. Lin wanted to put some intentional string crossings in, to change the color and bring out different voices of the harmony. So first Anthony tried it in third position, then first. Not easy to sight-read different fingerings in a well-practice piece, in front of an audience! This did add some interest.

"There's something shadowy about this theme and the violin's part in it," Lin said. "Enjoy the different colors of the different strings."

The final performer of the evening was Keila Wakao, who won the 2021 Menuhin Violin Competition Junior Division and studies at the New England Conservatory. She also plays the 1690 "Theodor" Stradivari violin!

Keila played the first movement of Brahms Sonata No. 2 in A major with pianist Evan Solomon. Wakao is a very kinetic player; she moves quite a lot, and she also produces a very beautiful sound on that Strad.

Lin praised her playing as "so heartfelt and singing and expressive!" Her interpretation was already quite good, Lin said, but he had a few more ideas.

First he talked about the "Magic Number Three" for Brahms. This movement is in three, and he also wanted her to think about all the ways that Brahms groups and divides three beats in a measure.

"Your basic approach is so singing - let some of that smoothness of the surface be broken," he said. I thought of a different way of saying what Lin was saying: don't pretend you are gliding on water that is as smooth as glass; acknowledge its turbulence.

Joseph Lin and student artist Keila Wakao.

Instead of all lyrical singing, he wanted the music to feel a variety of ways: spoken, interruptive, nudging. "Make the rhythm more of an expressive matter," he said. He also wanted her to show more awareness of the piano part - to actually reflect it in her own playing.

This was really good advice for Wakao and she responded so well, she really succeeded in enunciating more, making the music more meaningfully expressive, connecting better with the piano part that Evan Solomon was already playing so well.

"Listen to the piano and respond in your way," he said.

* * *

Before concluding, I wanted to return to the two very youngest players at this Symposium, Ria and Jayden. I noticed that both of these young musicians also were playing what appeared to be large (possibly full-size) violins, which of course produced wonderful sound. However, as a longtime teacher of very young children, my first reaction was to question the obviously over-sized instruments. Yes, these are fine young artists who truly deserve the finest instruments for all their practice and effort.

But we know that playing a too-big instrument can cause pain and injury, and pedagogy teachers consistently warn against it. Certainly a child's physical health should be a fundamental priority for both teachers and parents. So I don't want to see this become a trend. A better idea: with the proliferation of extremely accomplished luthiers making high-quality instrument these days, can we get someone to start a line of truly "Fine Fractionals"?

Obviously, parents, teachers and students must decide for themselves. But I do feel that it's an important issue - and institutions like Juilliard lead by example. With more and more children starting as toddlers and reaching a very advanced level before they reach an adult size, it's important to provide them what they need as young artists while also preserving their physical comfort and health.

You might also like:

- Master Class with Philip Setzer

- The 2025 Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies begins Monday at Juilliard

- All stories from Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies at Juilliard

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

I agree and I'm glad you added the comments about the very young performers using what liked full size violins. Every art form puts different demands on very young performers, and it seems to me that is not worth the risk to their health to play on instruments that are too big for them, even if in the short term it seems worthwhile. They were amazing players, but I do wonder what the toll will be down the road.

Very interesting to read details of this master class. Thank you!

I hope someone takes you up on your "Fine Fractionals" idea!

A viola student at that age will be playing a 13-14” viola — are you saying that kids just shouldn’t play the viola before they have finished growing? Or they should always play an instrument which is too small, so it isn’t any larger than the violin they would comfortably play? A 4/4 violin is going to be 13 7/8”-14 3/16” depending on maker and model.

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

June 25, 2025 at 03:32 PM · Thank you for sharing!