We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Master Class with Philip Setzer

NEW YORK - The 13th biennial Starling-DeLay Symposium on Violin Studies started on Monday at the Juilliard School with a master class with Philip Setzer.

Setzer emphasized the artistry behind the pedagogy while also sharing some of the stories that connect him to his own historical violin line: from his parents being members of the Cleveland Orchestra, to his teachers Josef Gingold and Oscar Shumsky, to his nearly five decades as the first violinist in the Emerson String Quartet.

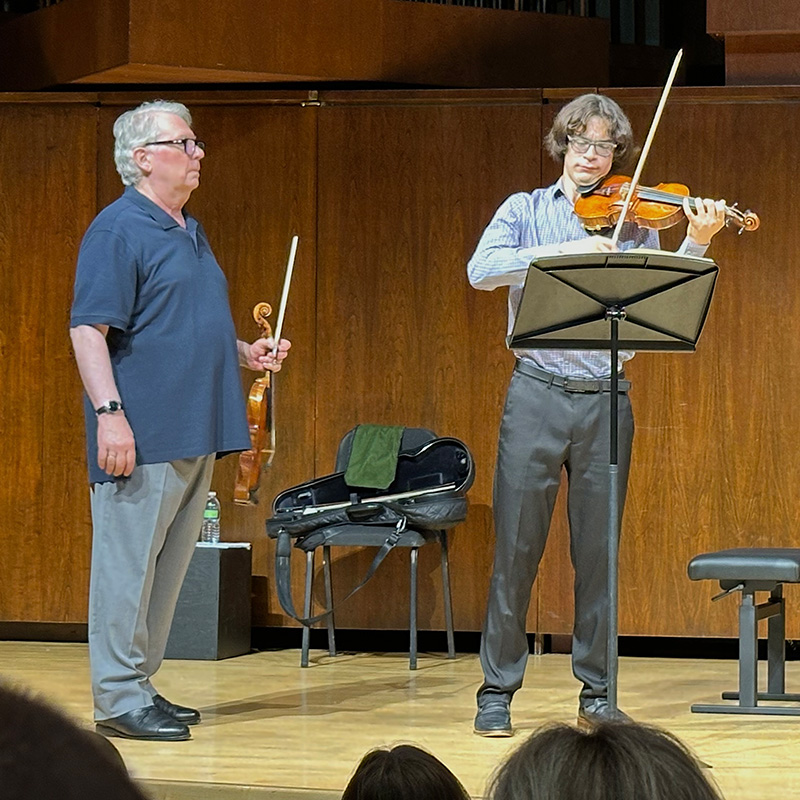

The afternoon began with Juilliard masters student Claire Arias-Kim, who performed the first movement of Johannes Brahms' Concerto in D major with pianist Pamela Viktoria Pyle. I was really impressed with her control of double stops in this major piece, and I also had to marvel again at how daunting it must be for anyone to play for this international audience of some 200+ experienced and avid violin teachers, sitting in the audience with their scores!

Philip Setzer and student artist Claire Arias-Kim, with pianist Pamela Viktoria Pyle.

After her performance Setzer started by sharing his own past experience as a student, playing the Brahms Violin Concerto for one of the finest violinists of the time - Nathan Milstein.

"He tore me to shreds!" Setzer said. Milstein himself was about to perform the Brahms, and Setzer could do nothing right. Then, after Milstein had his performance, Setzer played the piece for him again, "and this time, I could do no wrong!" No doubt, he had been nervous about his own performance.

As he did with all the students, Setzer actually went to the back of the hall to listen to Claire perform. He pointed out that most violin lessons are given at close range, with the teacher right next to the student, and it's different to hear someone from the back of the hall.

So - from the back of the hall, "I didn't hear your vibrato enough," he told her, adding, "I don't hear enough on the top of the note." Most of us violinists are told to vibrate up to the pitch but not above it.

Setzer shared that he and his quartet-mate, the cellist David Finckel, once did the kind of geeky thing that all of us in this particular room could appreciate: "we took all the great vibratos and slowed them down and listened to them," he said. And they didn't limit it to violinists or cellists. They took recordings of singers like Luciano Pavarotti and Renée Fleming, violinists like Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, etc. - and really analyzed them.

What did they discover? "All those great vibratos - they are mostly on the bottom of the pitch, but they also push the top." In other words, they don't just go up to the pitch, they push against it (maybe a little above?).

He had her do an experiment, playing the start of a melodic passage in the Brahms. She played just the first note with no vibrato, and also no bow speed, no pressure, no effort to "make sound," just slow bow, no sound. The result was pretty sad and puny (intentionally so!). Then, he told her to increase the bow speed, "try to get the top of the instrument to vibrate a little," he said, comparing the idea of getting a wine glass to ring by rubbing around the rim. "Now get the bottom to vibrate," a bit more pressure to make the fuller sound.

"Now add a little bit of vibrato and push the top of that sound," he said, telling her to try to feel that the top of the finger was pushing the "up side of the tone." He told her to listen for the "wuh-wuh-wuh-wuh" sound, the "w" being the part that pushes against the top. As she did this, the vibrato did become crisper, and the people in the back of the room attested that they could hear it better.

What an interesting concept! He said that projecting to the back of the room is "not just about playing louder, it's about projecting a sense of the beauty of the sound."

On another topic, he talked about shifts that have an unintentional glissando - his mother (who incidentally, was the sixth female violinist to ever play in the Cleveland Orchestra) called that kind of shift a "cat."

"She warned me about that kind of shift," he said. It might be okay in a vocal-sounding passage, but not in a fast passage. "Try a fingering that avoids a cat," he said.

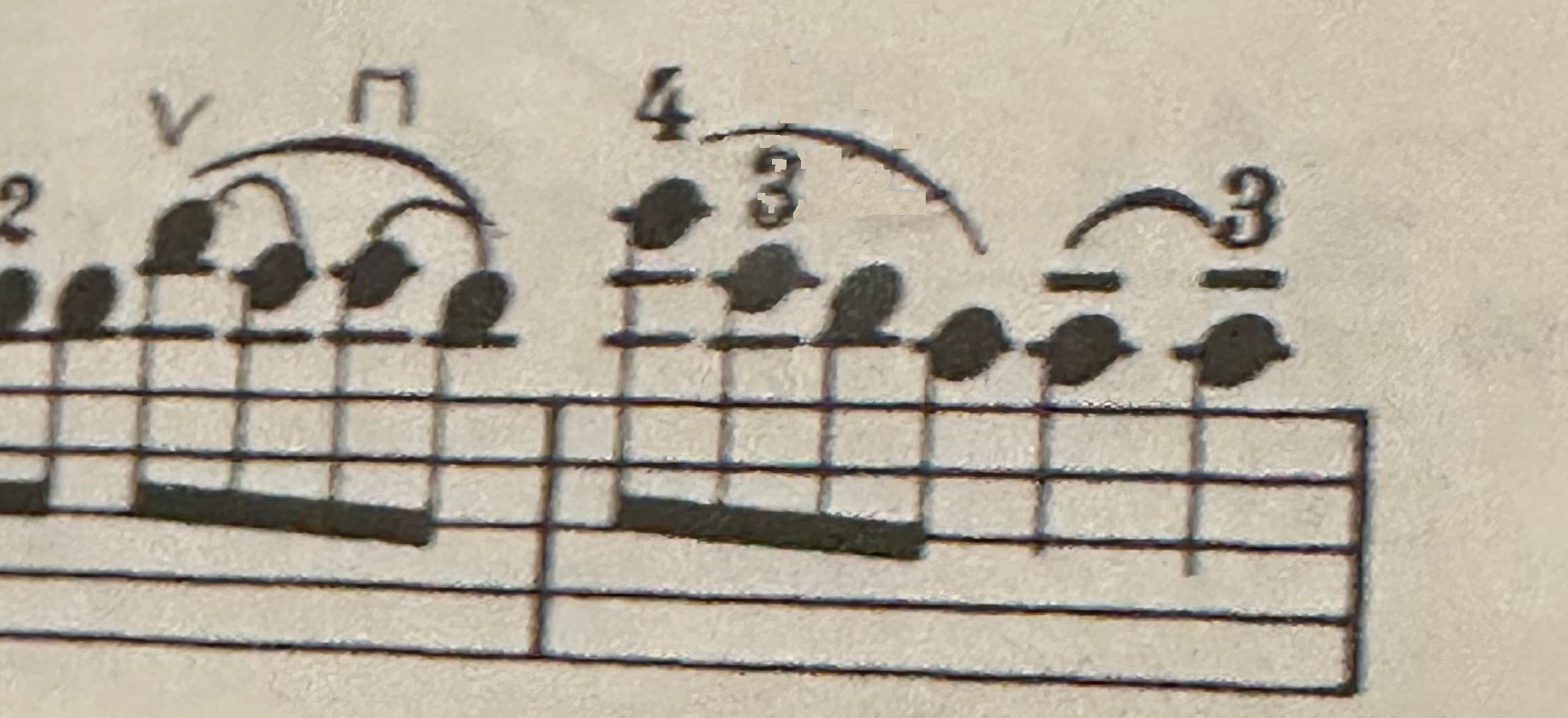

He also gave everyone a tip for the triple-stops at m. 164 in the Brahms...

...when you get to the long one, let go of the open E so that the middle-voice melody (the C) can come through. The E is often sustained, and that messes up that voicing.

Next was Dániel Hodos - whose studies have taken him from the Liszt Academy in Budapest to the Colburn School in LA and now to the Hochschule für Musik in Leipzig - performed the first movement of Robert Schumann's Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 121 with pianist Evan Solomon. I don't know this piece, but looking at the Opus number I wondered if it was late Schumann (it was). Hodas had an elegant sound, good sense of timing, and there was a real ease in his playing.

Philip Setzer and student artist Dániel Hodos.

I felt vindicated when Setzer said that, while he has played Schumann's A minor sonata, he has not played this one. Setzer explained that this piece "could easily be done on viola - it's very low." Few of the notes are high, and that presents some unique challenges for getting it across.

Having listened again from the back of the hall, he said there was "not enough articulation on the low notes" - with so many low notes, one has to articulate them even more.

He compared it to the difference between acting for film and acting for the stage - the camera is close and picks up so much, "things you do on stage would be too big for film, and vice-versa." Similarly, to get across a piece in a live performance, in a large hall, it all has to be bigger, with more dynamics, more articulation.

He quoted someone (I'm not sure who!) saying that "there are places where the violin needs to play more like the piano and the piano needs to play more like the violin" - dial up the percussion!

"My problem with this movement is - it's a little repetitious," Setzer said. So how does one make that interesting?

He told Evan not to make it so beautiful, and to Dániel, "this is too normal," Setzer said. "This is late Schumann. He was not in a good place." Schumann was terribly mentally ill - nearly ready for the sanitorium at the time that he wrote this piece. Once institutionalized, he couldn't see his beloved wife Clara. When she did finally come to visit him, he died just two days later.

"You hear that in this piece. You have to pretend you aren't as healthy as you are," he told Dániel. "You are an actor now."

When it comes to Robert Schumann's terrible mental state, "you don't have to talk about it or put it in the program notes, you have to do it." It needs to be in the music. "If you have any crazy idea, you have to try it."

For example, in a place with repeated up-bows, with a little rest between, this is like someone catching his breath, or unable to. To get the feeling of it, "actually breathe on the rests," Setzer said. "The breath is actually more important than the notes."

"Can you get even crazier here?"

Dániel responded really well to these ideas, putting a little more drama, a little more sinister tone into the music. They had good teacher-student chemistry - that is a magical thing.

Next we heard J.S. Bach's famous "Chaconne" from the Partita in D minor, played by Canadian-German violinist Emrik Revermann, who has won many prizes and scholarships (including one that was the subject of a recent article here the Arkady Fomin Scholarship).

With time at a premium for the master class, Setzer told him to play most but not all of the piece, stopping sometime after the point where the piece switches from minor to major.

But after Emrik had played just a few lines of the piece, I wanted to hear him play it to the end. Clearly an independent thinker, Emrik had found unique ways to bring out the Baroque sensibility in this piece while also putting his own elegant stamp on it, a sophisticated interpretation. He seemed to revel in creating a ringing and pure Baroque sound, taking the piece at a pretty fast clip, which made fast notes sound like decoration. He varied the tempo - but in a way that felt very natural. And at that start of the "major" section, he created quite a silence and stillness.

Setzer told him to "keep all those ideas you have - don't throw them out." But with a piece like the Chaconne - something people study and play for a lifetime - Setzer also had a lot of ideas to share.

Philip Setzer and student artist Emrik Revermann.

Setzer felt the beginning was a bit fast to establish the grandeur of the piece. With Bach being an organist who played every week, it's hard to believe he wouldn't have tried this piece out on the organ, Setzer said. "This would be perfect to play on the organ." And on the organ, it would certainly be stately and grand.

"I liked that you changed the character of each variation, without changing the tempo too much," Setzer said, adding that "there is something hypnotic about the way the chords change," and a consistent tempo helps set that kind of spell.

Setzer talked about how his own teacher, Shumsky, played the piece, recalling hearing him play it at a church in Oberlin, while a thunderstorm raged outside. He offered a Shumsky idea: playing the beginning "as it comes" - down, up down; up, down up - only doing one bow retake for the final set of chords. (Listen to Shumsky's recording here!)

Also, Setzer talked about the general practice of the rebound chords, where violinists play the chord from bottom to top and then whip the bow back to the bottom, for the purpose of voicing. This can sound a bit funny. Instead, he suggests playing the bottom of the chord on the beat, by itself, followed by the rest of the chord. This gives it enough emphasis to be heard as intended, in terms of the voicing.

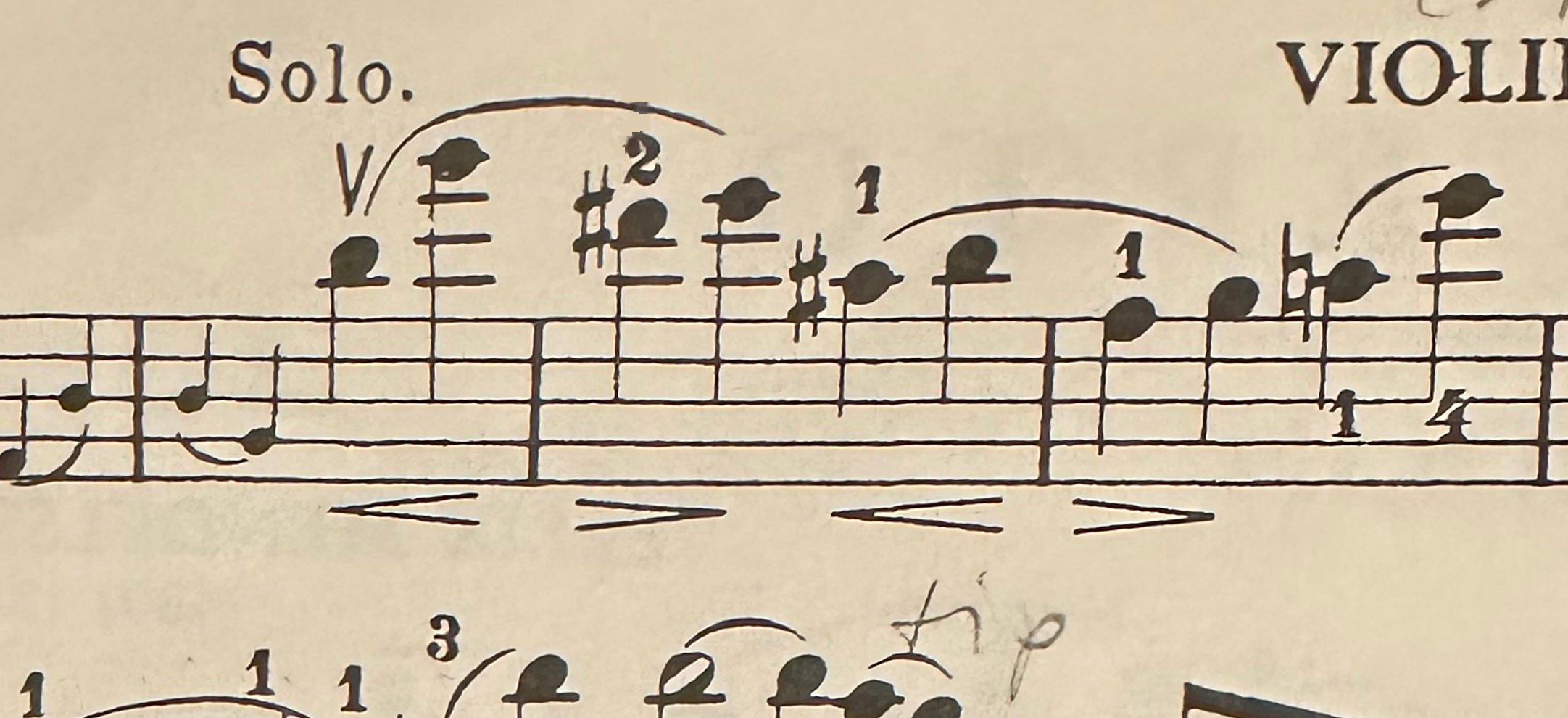

Emmanuelle (Ellie) Sievens treated us to the first movement of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, played with Pamela Viktoria Pyle. Ellie had mastered the piece well, playing with big, straight bows and a textbook-correct left hand.

In working with Ellie, Setzer went through the Mendelssohn - such a frequently-played and frequently-taught piece - and posed some pointed questions about our collective habits regarding this piece.

As someone who spent most of his life playing in a professional quartet rather than playing solos, Setzer is the perfect person to raise questions and also offer some ideas that are well-grounded in musical artistry and proficiency on the violin. I can't name them all, but a few of my favorites:

Why do we do this fingering that never sounds good? Why not just stay in position and go over to the A string?

Why do we do all this sliding, especially down to first position? It sounds...slide-y. It would sound just fine to play the F# and G in third position on the A string.

And best of all: "Can we try not playing the cadenza, until the cadenza is written?" Typically violinists start slowing way down (and rubato-ing and cadenza-ing) around that long G# between N and O. How about keeping it fast and fiery, all the way until nine measures after O, where it actually says "Cadenza ad libitum"?

Philip Setzer and student artist Ellie Sievers, and pianist Pamela Viktoria Pyle.

So Ellie, with Pamela at the piano, tried doing this. With so much ingrained tradition, it took a few do-overs and coaching from Setzer, but they did it, and it really sounded different when they kept the tempo going, all the way up to the cadenza.

Setzer encouraged Ellie - and everyone - to keep looking for solutions, even when the trail has been well-blazed for centuries.

"Don't always do what everyone else does," Setzer said, "you might find a better solution - the cadenza should be a surprise."

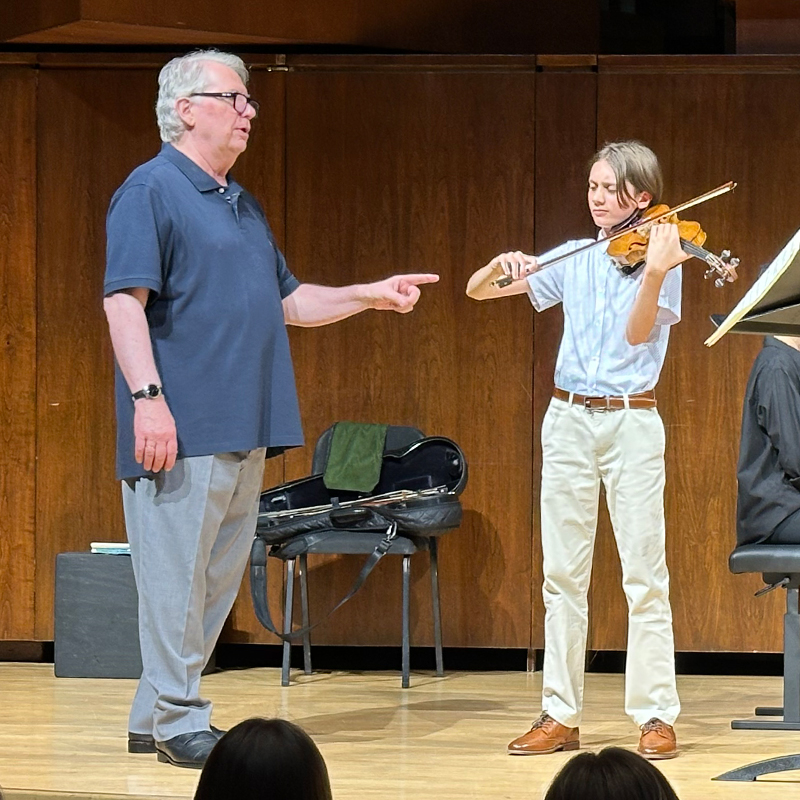

To conclude the master class, Maxwell Brown performed Ravel's "Tzigane" with pianist Jinhee Park. Maxwell, a student at Juilliard Pre-College, is participating in the Symposium for the second time, having also been a student artist in 2023. Maxwell played with great stage presence and impressive accuracy when it came to delivering pitch; Setzer emphasized rhythmic delivery.

Philip Setzer and student artist Maxwell Brown.

First, Setzer wanted to concentrate on silences.

"All the gestures are good, you just need more time in between them," Setzer said. "That's where you create the drama: in the silences."

Setzer demonstrated by putting some silences in his speaking, which did feel quite dramatic.

"Enjoy the fact that you just freeze," he said.

He also wanted Maxwell to pay closer attention to what Ravel wrote, in terms of rhythm.

Maxwell's pickup notes were all sounding the same length, but sometimes Ravel writes a 16th pickup, sometimes a 32nd note. Setzer also emphasized that it is important to play the rhythm exactly as written, before distorting it for musical purposes.

He also talked about his experience in watching Roma musicians play - this piece was inspired by Roma (once called gypsy) music, and it is very improvisatory.

In concluding the master class, Setzer told a story about Dorothy DeLay, the great Juilliard pedagogue who founded this symposium. Once at Aspen, DeLay was ill and asked him to teach a three-hour master class in her place. After a few hours he noticed that she had actually come to the master class - she was sitting in her wheelchair, in the back, in the shadows. She had come because she wanted to see what he was doing.

"What made the biggest impression on me was how curious she was," he said. With all her experience, "she wanted to see what we would work on, what I would pick up on, in her students."

"Don't lose your curiosity," Setzer said. Even - maybe especially - in a world over-saturated with information, it's important to follow your own mind's curiosity about the world. "Try to keep learning."

You might also like:

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

June 24, 2025 at 07:23 PM · Eugene Drucker might be a little surprised to hear that Phil was THE 1st violin of the quartet, given that they divided the responsibilities equally. That said, I do prefer Phil’s playing, possibly because I have heard more of it.

I once told one of them backstage at a Beethoven performance how much I had enjoyed their recorded performance of the Schumann piano quartet…only to be told that I was congratulating the wrong violinist! ??

Nick Canellakis had an amusing episode of “Conversations with Nick” featuring the Emerson: https://youtu.be/81QTpl8aP00?si=unTDwt-g0FuSRZez