We have thousands of human-written stories, discussions, interviews and reviews from today through the past 20+ years. Find them here:

Weekend vote: Is it ever acceptable for musicians to collectively refuse to perform a piece of music?

A news story caught my eye in the last week - about an orchestra that canceled the performance of a new piece.

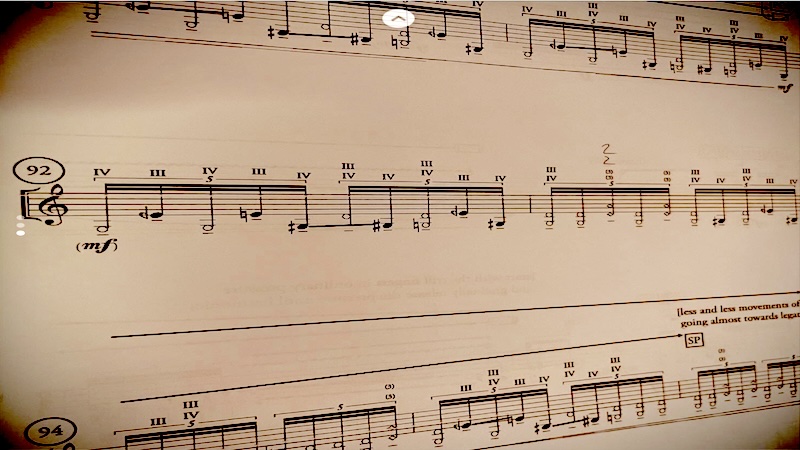

Apparently 30 percent of the musicians of the Essen Philharmonic raised serious concerns about performing Italian composer Clara Iannotta’s violin concerto "sand like gold-leaf smithereens" at a set of concerts Oct. 30 and 31, part of Festival NOW!. The performance by German violinist Carolin Widmann was to be the premiere of the work, which was for detuned violin, orchestra and electronics. It was commissioned for the festival.

The performance of the piece was canceled 10 days before the concert (at which Widmann played the Berg Violin Concerto instead.) Widmann took to Instagram to say she was "heartbroken"; the composer Iannotta went further, saying on her website that "what concerns me most is a profound lack of curiosity. An orchestra, as one of the most powerful and symbolic bodies in musical life, cannot claim to represent our time if it accepts only one type of music."

However. The composer delivered the full score and parts to the orchestra just two weeks before the concert, on October 3. It was supposed to be in by August 2025. The work required that the musicians use extended techniques and perform on extra instruments and objects. Specifically they were being asked to bow on Styrofoam plates and to use stones in close proximity to their instruments. That's a big ask when bows are often worth thousands, and violins are worth tens of thousands.

It sounds like much of the orchestra was willing to try to make this happen, but about 30 percent raised legitimate concerns, and there just wasn't enough time for management to work out all the details to address those concerns.

"This cancellation, made after careful consideration, was based on the fact that, despite extensive efforts from all sides, the short timeframe following the arrival of the concert score did not allow for professional rehearsal and performance of the work," said the Essen Philharmonic on its website. "Furthermore, the short notice made it impossible to definitively clarify all questions regarding potential special fees."

"I acknowledge that I delivered the orchestral score later than ideal," Iannotta wrote on Instagram. "The soloist already had the full part and recorded it on September 6, while I sent two-thirds of the score to the conductor in mid-September and the complete score to the orchestra on October 3 — but I also took full responsibility for providing and preparing all the objects at my own expense (over €2,000) and worked closely with Elena Schwarz to ensure sufficient rehearsal time."

For me, all this raises the question: how much is too much to ask of musicians, and is it ever okay to draw the line? Please participate in the vote, and share your thoughts and experiences in the comments. What do you think about the use of extended techniques, extra objects, etc. in new music? How do you feel about short time-lines for preparing a performance of a new work?

* * *

Enjoying Violinist.com? Click here to sign up for our free, bi-weekly email newsletter. And if you've already signed up, please invite your friends! Thank you.

Replies

I firmly believe that musicians should be able to decline to perform music. However, I believe such refusals should be based on serious grounds, such as illness, or refusal to perform music that espouses views that are offensive to the performer.

I think that modern performers are spoiled. In the past the work may not have been completed two weeks before the performance.

In terms of extended techniques, performers have become acoustomed to their instruments as they know them. In the past there was more willingness to innovate.

Much of this relates to newly composed music. Such music can of course be of poor quality. Some extended techniques may not cut the mustard. But judging the techniques should be based on the music, as opposed to the willingness of performers.

The question is, who will pay for the damages to a fine instrument or for a replacement instrument if one is damaged in the performance of a piece like this? There’s innovation and then there’s putting one’s instrument in danger. Perhaps a compromise could be found where the orchestra acquires less valuable instruments for a piece, etc.

I won't play or sing anything by Carl Orff.

So if a piece of "music" called for a first violin to play the tuba, should the violinist be able to decline? I'd say so. Shouldn't be required to play dinnerware or rocks either.

Many years ago when I was with the Wiener Tonkunstler Orchestra, we were commissioned to perform a piece of music by a composer from Texas. During the first rehearsal, the orchestra stopped playing and said that the music was not playable. I didn't speak German all that well so I don't really know what happened but the orchestra refused to play.

They should have postponed sooner. Insisting that the terms of ones contract be fulfilled is not a "profound lack of curiosity." The Essen Phil can write her a check for her €2000 in rocks and styrofoam plates. After reading about this episode in a few places, I can't shake the feeling that the members of the orchestra gave it their best, but that there were too many questions and that it wasn't easy to find the right people to ask.

Adrian Heath: %100

Substitute instruments and bows could be solve the issue!

Gulia, good idea. When orchestras are contracted to play out in inclimate conditions, they use substitute instruments.

Is the composer gonna pay for new bow hair, after it’s contaminated with styrofoam? Will she pay for damage from stones?

Will she forgive the orchestra and the conductor if it isn’t perfect, after two weeks of practice in a different tuning?

In a professional orchestra the musicians are represented by a union which will be responsible for negotiating with the orchestra management... the orchestra can't normally simply take a vote and decide not to perform the program selected by the management and conductor.

The "composer" sounds like a hack who didn't want to take responsibility for being tardy and shifting blame on the orchestra. Typical garbage by these younger generations. Let alone the absurd "instruments". This is why I hate contemporary classical. It's like these "composers" (and I use that term loosely), come up with more and more absurd garbage thats supposedly art when theres no thought or actual art. Like the artist that stuck duct tape to a wall with a banana. Its ridiculous. I wish these so called artists actually made real art instead scamming and grifting people outta their hard earned money.

John Cage strikes again!

How often does a work by a composer of the polystyrene school take up a place in the repertoire?

I think it's very important to make it very clear to the general public, that musicians are NOT slaves who have to be subjected to whatever the management says, and that we as musicians first of all, have to protect our instruments, which are a huge investment, and even though they are generally insured, causing damages will devaluate it.

People generally think, that we are paid, therefore we must play... WRONG...!!!

We play for your enjoyment, but we are artist first of all, and secondly you pay to listen to our music making.

Thank you

Richard, you ask jokingly about composers of the polystyrene school getting a place in the repertoire.

Music employs objects to make sounds. Sometimes they become canonical. There was a time when bows were not used in music. Imagine what might have been said about their first use.

There are also examples of utilitarian instruments being used in music, such as Mozart's posthorn serenade. Today, no one bats an eye over its use. Should Mozart be removed from the canon for being a polystyrene composer?

Natürlich waren bei den verschiedenen Ausführungen extremer Spielarten auch manchmal unsere kostbaren Instrumente in Gefahr. Da aber bei einer Vielzahl neuer Kompositionen die klassische Klangschönheit durch den Wunsch nach perkussiven Elementen in den Hintergrund tritt, ersetzten wir in diesen Fällen unsere alten, teuren Instrumente durch Zweitinstrumente billiger Massen-fabrikation, wie sie in Bayern oder in Fernost hergestellt werden. Den Komponisten ging es um die Suche nach neuem Klangausdruck auf der Grundlage solider Kenntnis und Professionalität der Interpreten auf ihren Instrumenten. Die billigen Zweitinstrumente verhalfen uns zu mutigerem Herangehen an die Musikpassagen, durch deren Ausführung bei unkontrollierter Spielweise die Instrumente beschä-digt werden könnten. Kratzer auf dem empfindlichen Lack stellen auffällige ästhetische Schäden dar, abgesehen von Absplitterungen der Holzteile wie z. B. die stark gefährdeten Ränder der Zargen. Auch Stoßstellen an Boden, Decke oder Schnecke sind an kostbaren Instrumenten meist unreparierbare, sehr ärgerliche Schäden. Das Sich-Lösen der Saitenumspannung bei zu starker Beanspruchung durch harte oder raue Gegenstände kann ebenfalls zu starker Spieleinschränkung führen. Hier allerdings hilft ein sehr schnelles Auswechseln der beschädigten durch bereits gespielte Saiten.

Die Anschaffung dieser Zusatzinstrumente machte nicht nur uns spieltechnisch mutiger, sondern auch die Komponisten. Sie hatten offensichtlich ihre Freude daran, für ein Ensemble zu komponieren, das ihre bis dahin unerfüllten Sehnsüchte und Träume nach radikaler Klangveränderung auf klassischen Musikinstrumenten nahezu unbe-grenzt zu erfüllen bereit war.

Wir wissen aber auch: wo „gesägt“ wird, fallen Späne. Da geschah es eines Tages, dass wir von einem Komponisten aus der Gegend von Frankfurt ein Stück zugesandt bekamen. Ich möchte seinen Namen ungenannt lassen, um nicht Schuld an seiner zukünftigen Kompo-nistenkarriere zu sein, wie auch immer sie verlaufen wird. Er war für uns ein Unbekannter und hatte ein Stück für uns geschrieben, dessen Titel ich vergessen habe. Die Partituren waren, soweit ich mich erinnern kann, in gut lesbarer Notierung geschrieben, was nicht häufig die Regel war, und wir fingen an, das Stück mit unseren Instrumenten durchzusehen, also zu proben. Es beeindruckte uns zunächst wenig, was sich jedoch unserer Erfahrung nach im weiteren Studium ändern könnte. Mit dem Komponisten war ein Termin vereinbart worden, zu dem er zwecks gemeinsamer Erarbeitung nach Köln zu kommen vorgeschlagen hatte.

Noch während der Proben ohne den Komponisten gelangten wir in der Mitte des Stückes an eine Passage, die wir beabsichtigten, nicht in der Form zu interpretieren, wie sie der Komponist in der Partitur dokumentiert hatte. Er schrieb vor, dass wir um eines klangvollen perkussiven Effektes willen mit dem Frosch unserer Bögen (das ist eine Spannschraube aus Metall!) auf den Instrumentenkorpus klopfen sollten, und zwar im Fortissimo. Die Folgen davon wären zumindest tiefgehende Schäden am Lack, wenn nicht gar Dellen oder Löcher im Holz oder ein Zerbersten des Instrumentes gewesen, also eine Totalzerstörung. Unsere mehrjährige Erfahrung mit der In-strumentenkunde einiger Komponisten ließ uns eher schmunzeln, als uns darüber aufzuregen. Wir würden den Komponisten schon davon überzeugen können, dass sich kein Musiker dazu bereit erklären würde, auf der Bühne sein Instrument mutwillig zu zerstören – nur wegen einer kurzzeitigen Effekthascherei, die mit einer anderen Handhabung durchaus lösbar wäre. Wir waren uns einig und warteten den Besuch ab. -

Der Komponist hörte aufmerksam seinem Werk zu, das wir ihm vorspielten, bis wir an die betreffende Stelle kamen, die wir beabsichtigten, ihm in dieser „Exekution“, selbst auf unseren Billig-Instrumenten auszureden, zumindest aber zu verändern. Wir boten ihm an, mit unseren Bögen auf die Holz-Notenpulte zu klopfen. Nein. Wir probierten es mit hohlen Holzkisten, die eine klangvollere und etwas edlere Resonanz erzeugen. Nein. Wir überlegten und machten noch einige Vorschläge, aber der Herr Komponist bestand auf seiner erdachten Ausführung, mit der Bogenschraube auf das Instrument zu hämmern, im Fortissimo. Unsere Sorge um die Instrumente, Erklärungen, Ersatz-Angebote usw. schlugen fehl. Er blieb uneinsichtig und stur. Nach geraumer Zeit waren nicht nur unsere Angebote verschiedener Vorschläge mit Spielmöglichkeiten erschöpft, sondern auch meine Geduld. Wir hatten für dieses Problem schon genug Zeit vergeudet, und ich sah mich am Ende unserer Vorschläge an diesen Ochsen, der mit den Hörnern durch die Wand wollte (in unserem Fall mit dem Frosch durch die Decke), nahm kurzerhand seinen Viola-Part von meinem Notenpult, zerriss ihn vor seinen erschreckten Augen, legte die Papierfetzen in seine Arme und sagte: „Alles Gute weiterhin!“ Selbst meine beiden Kollegen waren von meinem spontanen Handeln sehr überrascht, da sie wussten, wie pfleglich ich in der Regel mit Notenmaterial umgehe. Das schließt sogar ein, dass ich Notenmaterial, auf dem Boden liegend, nicht dulde, niemals, nirgendwo.

Niemals mehr in meinem Leben musste ich aus diesen oder ähnlichen Gründen von derart verabscheuungswürdigen Handlungen Gebrauch machen, und niemals mehr habe ich etwas von diesem Geigenkiller gehört – in welcher Form auch immer.

*) Die Behandlungen mit ungewöhnlichen Objekten, besonders bei dem Werk „Aus dem Nachlass“ von Mauricio Kagel, veranlassten mich, meine Zweit-bratsche fortan „Kagliano“ zu nennen - nach der berühmten italienischen Familie der Geigenbaumeister Gagliano (Neapel um 1700).

aus: Eckart Schloifer, Band 4 "Begegnungen und Autobiographisches", 2016 (Privatedition, zu beziehen über ec.shloi@gmx.de)

It isn't just composers who can sometimes make excessive demands of the players. I thought the Aurora Orchestra came pretty close to the line in their dramatized lecture/performance of Shostakovich 5 at the BBC Proms a few months ago, when presumably in order to make some historico-political point the leader was carried across the platform by 4 assistants while playing a solo from a horizontal position. Somehow she brought it off with a commendably steady tone.

Eckhart, could you put your post through a translation app and post again, please.

There have been occasions when I have gone to the conductor and said "your concertmaster (me) cannot play this" and pointed out specific non-idiomatic or ignorant violin writing; implying that the entire 1st violin section can't play it either. Maybe the piece gets cut.

There are special summer festival orchestras, like our local Cabrillo Fest. which specialize in new and difficult music. The orchestra is young, enthusiastic, pro-level technique, with great sight-reading skills.

I had a life-time quota of this stuff when I was at UC San Diego. My suspicion is that the avant-garde is a way for artists to not need to master technique and theory.

Less than two weeks to learn a piece including objects that could seriously damage expensive instruments and bows, along with a composer who thinks this type of composition is perfectly acceptable for the sake of art. I think most musicians would soundly reject such a situation, and rightly so. The composer wouldn't be held liable if the players suffered hundreds of thousands of dollars in combined damage after all. I did read Ms. Iannotta's commentary and response to the situation and thought it was very self-serving.

I was going to reply "No" but then I read about the stones :-)

Great story Eckart, thanks for sharing!

As explained well by Eckart, musicians performing such music will typically use a cheap but still-decent instrument instead of their fine, main instrument. But there are limits! (And, such "cheap" instruments may still easily cost a few thousand.)

The following is how google translated Eckart's post for me. Eckart, I hope this is ok to place here. If this does not reflect your posting properly, let me know and I'll remove it!

Of course, with the various designs of extreme varieties, our precious instruments were sometimes in danger. However, since classical sound beauty fades into the background in a large number of new compositions by the desire for percussive elements, we replaced our old, expensive instruments with second instruments of cheap mass production, such as those produced in Bavaria or in the Far East. The composers were concerned with finding new sound expression based on the solid knowledge and professionalism of the performers on their instruments. The cheap second instruments helped us to take a bolder approach to musical passages, the execution of which could damage the instruments if they were played uncontrollably. Scratches on the delicate paint represent conspicuous aesthetic damage, apart from chipping off the wooden parts, such as the highly endangered edges of the frames. Shocks on the floor, ceiling or snail are also usually unrepairable, very annoying damage to precious instruments. Releasing the string tension when too much strain is caused by hard or rough objects can also lead to severe play restriction. Here, however, a very fast replacement of the damaged strings already played helps.

The acquisition of these additional instruments not only made us more courageous in terms of playing technology, but also made the composers more courageous. They obviously enjoyed composing for an ensemble that was almost unlimited in fulfilling their previously unfulfilled longings and dreams for radical sound changes on classical musical instruments.

But we also know that where "sawing" is done, chips fall. One day we were sent a piece by a composer from the Frankfurt area. I want to leave his name unnamed so as not to blame for his future composing career, however it may go. He was an unknown to us and had written a piece for us, the title of which I have forgotten. The scores were, as far as I can remember, written in a readable note, which was not often the rule, and we began to look through the piece with our instruments, i.e. to rehearse. We were not impressed at first, but in our experience this could change in further study. An appointment had been agreed with the composer, for which he had proposed to come to Cologne for the purpose of joint development.

Even during rehearsals without the composer, we arrived at a passage in the middle of the piece that we intended not to interpret in the form that the composer had documented in the score. He dictated that for the sake of a sonorous percussive effect, we use the frog of our bows (that's a metal clamping screw!) should tap on the instrument body, in the fortissimo. The consequences of this would have been at least profound damage to the paint, if not dents or holes in the wood or a bursting of the instrument, i.e. a total destruction. Our many years of experience with the instrumentation of some composers made us smile rather than get upset about it. We would be able to convince the composer that no musician would agree to deliberately destroy his instrument on stage - only because of a short-term showmanship that could be solved with a different handling. We agreed and waited for the visit.

The composer listened attentively to his work, which we played to him until we came to the place in question, which we intended to talk to him in this "execution," even on our cheap instruments, but at least to change it. We offered to tap him with our bows on the wooden note desks. No. We tried hollow wooden boxes, which create a more sonorous and somewhat nobler resonance. No. We considered and made some suggestions, but the composer insisted on his devised execution of hammering the bow screw on the instrument at Fortissimo. Our concern for the instruments, explanations, replacement offers, etc. failed. He remained unapologetic and stubborn. After some time, not only were our offers of various suggestions exhausted with play options, but also my patience. We had already wasted enough time on this problem, and at the end of our proposals I saw myself at this ox, which wanted to go through the wall with its horns (in our case with the frog through the ceiling), took its viola part from my music stand, tore it apart in front of his frightened eyes, put the scraps of paper in his arms and said, "All the best!" Even my two colleagues were very surprised by my spontaneous actions, as they knew how carefully I usually handle grade material. This even includes not condoning sheet music lying on the floor, never, nowhere.

Never again in my life have I had to make use of such despicable acts for these or similar reasons, and never again have I heard of this violin killer - in any form whatsoever.

The treatments with unusual objects, especially in the work "From the Estate" by Mauricio Kagel, prompted me to call my second viola "Kagliano" - after the famous Italian family of violin makers Gagliano (Naples around 1700).

from: Eckart Schloifer, Volume 4 "Encounters and Autobiographical," 2016 (Private edition, available at ec.shloi@gmx.de)

"I acknowledge that I delivered the orchestral score later than ideal,"

That’s all you really need to know. The conductor turned in a half baked product last minute and is dealing with the consequences. “Later than ideal” is pure fallacy; it was over a month late.

As Adrian points out in reply #1, Laurie has shot herself in the foot with the word "ever", or by not including the response "it depends": invent your own scenario. Are you going to perform on the lip of an erupting volcano? Are desks 1&2 going to smash their instruments together? It makes me wonder about the imaginations of the 25 people who answered "no". Still, it has been a conversation.

But, Laurie, while you are still getting 600 responses - Fiddlerman polls are nowadays lucky to get 6 - you could use that opportunity to devise valid and useful polls.

Andrew - you seem to be in a tiny minority here so I guess the poll must be invalid?

Could it be the definition of "music" that's the problem?

Yes, a definition of music is part of the issue. A universal definition, open to all cultures, would be; sound organized by aesthetics. Random noise doesn't count. Organized noise; an all- percussion piece does qualify. The traditional conservative definition would be; a combination of melody, harmony, and rhythm, plus a text when there is a singer. By that definition Rap, and some traditional musics from the far east are not music. [ Rap,hip-hop = zero melody, zero harmony, boring rhythm, awful text].

Joel, 4'33" by Cage would not meet your universal definition.

Certainly, the composer not supplying the music on time is unfortunate.

I wonder if the work will be reschedualled, or if this really is a case in which the ensemble simply refuses to perform it. (They knew approximately what they were getting in to, in commisioning a work by her. It is not a surprise.)

Dear friends, Eckart's contribution is quite interesting, here is the translation:

Of course, the various extreme playing styles sometimes put our precious instruments at risk. However, since many new compositions prioritize percussive elements over classical tonal beauty, we replaced our old, expensive instruments in these cases with cheaper, mass-produced second instruments, such as those made in Bavaria or the Far East. The composers were seeking new sonic expression based on the performers' solid knowledge and professionalism on their instruments. The inexpensive second instruments allowed us to approach musical passages more boldly, passages that could damage the instruments if played uncontrollably. Scratches on the delicate varnish represent noticeable aesthetic damage, not to mention splintering of the wooden parts, such as the particularly vulnerable edges of the ribs. Impacts on the back, top, or scroll are also usually irreparable and extremely annoying damage to valuable instruments. Loosening of the strings due to excessive stress from hard or rough objects can also severely restrict playability. In this case, however, quickly replacing the damaged strings with ones that have already been played with will help.

The acquisition of these additional instruments not only made us more daring technically, but also the composers. They clearly enjoyed composing for an ensemble that was almost limitlessly willing to fulfill their hitherto unfulfilled longings and dreams for radical sound transformation on classical instruments.

But we also know: where there's sawing, there are shavings. So it happened one day that we received a piece from a composer from the Frankfurt area. I'd rather not mention his name, so as not to be responsible for his future career as a composer, however it may turn out. He was unknown to us and had written a piece for us, the title of which I've forgotten. The scores were, as far as I can remember, written in easily legible notation, which wasn't always the case, and we began to go through the piece with our instruments, that is, to rehearse it. Initially, it didn't impress us much, but in our experience, that could change as we continued our studies. An appointment had been arranged with the composer, who had suggested coming to Cologne for the purpose of collaborative work.

Even during rehearsals without the composer present, we reached a passage midway through the piece that we intended to interpret differently than the composer had documented in the score. He prescribed that, for the sake of a sonorous percussive effect, we should tap the frog of our bows (that's a metal tension screw!) against the instrument's body, and do so fortissimo. The consequences would have been, at the very least, deep damage to the varnish, if not dents or holes in the wood, or even the shattering of the instrument—in other words, total destruction. Our years of experience with the instrumental nuances of some composers made us chuckle rather than get upset. We were confident we could convince the composer that no musician would willingly destroy their instrument on stage—just for a fleeting effect that could easily be achieved with a different approach. We were in agreement and waited for his visit.

The composer listened attentively to the piece we played for him until we reached the passage we intended to dissuade him from performing, even on our cheap instruments, or at least to alter. We suggested tapping our bows on the wooden music stands. No. We tried hollow wooden boxes, which produce a more resonant and somewhat more refined sound. No. We considered our options and made several more suggestions, but the composer insisted on his chosen method of hammering the instrument with the bow screw, in fortissimo. Our efforts to protect the instruments, our explanations, our offers of alternatives, and so on, were all in vain. He remained unreasonable and stubborn. After some time, not only were our suggestions for playing the piece exhausted, but so was my patience.We had already wasted enough time on this problem, and seeing myself at the end of our suggestions, this stubborn mule who wanted to go through the wall with his horns (in our case, through the ceiling with his frog), I simply grabbed his viola part from my music stand, tore it up in front of his horrified eyes, placed the scraps of paper in his arms, and said, "All the best!" Even my two colleagues were very surprised by my spontaneous action, as they knew how carefully I usually handle sheet music. This even includes the fact that I never tolerate sheet music lying on the floor, never, anywhere.

Never again in my life have I had to resort to such abhorrent acts for these or similar reasons, and never again have I heard anything about this violin killer—in any form whatsoever.

*) The treatments with unusual objects, especially in the work "From the Estate" by Mauricio Kagel, led me to henceforth name my second viola "Kagliano"—after the famous Italian family of violin makers, the Gaglianos (Naples, c. 1700).

From: Eckart Schloifer, Volume 4 "Encounters and Autobiographical Writings," 2016 (Private edition, available from ec.shloi@gmx.de)

My god, Joel, I’m so glad I’m not the only one who feels that way about rap and hip hop.

Have you heard of the new genre of music? It’s a blend of Country and rap…..

It’s called Crap.

"Are you going to perform on the lip of an erupting volcano?"

I should probably point out that this wasn't a completely flippant example - Werner Herzog nominally made a movie under those conditions. (in fact he took a film crew to Montserrat after the eruption had been predicted and documented the locals who had refused to take part in the evacuation)

John Cage's 4'33" of silence is like hanging a picture frame in a gallery without the picture, a humorous, provocative statement. Rap and hip-hop is infecting other countries. It grieves me to hear it in German or Spanish.

Oh now come on guys. Let's not crap on rap, or on any entire genre of music. I like a great deal of rap, hip-hop, EDM, rock 'n' roll, country... It's all on my playlist.

I also like a great deal of contemporary classical music, but certainly not if I have to bang on my 200-year-old fiddle with a rock or metal bow screw....

Synthesizers might do a better job in producing unusual sounds as there are a lot of pre-recorded sounds available in sound effect libraries that are ready for manipulation.

Sometimes a synthesized sound is preferable when the composer demands something that is not easily done on an acoustic instrument: for instance, a fast and complex passage of 16th note pizzicato (used in Enya’s Orinoco Flow).

Raymond has offered a good suggestion for composers who want peculiar or otherworldly noises: the synthesizer. As Mark pointed out above, new modes of playing and new music technology appear from time to time, though I doubt whether the bow appeared on its own, separate from the rabel, rebec or crwth. Mahler's box and hammer or Villa-Lobos' jet engine probably have to be used with care, but I don't know of any damage caused by them to other valuable instruments. My final thought on the polystyrene school is that the Essen Philharmonic was being asked to take great risks for little if any musical progress.

I like "soundscapes", but they don't have to involve abusing musical instruments.

I thought I had said everything that occurred to me on this topic, but listening to 'The Rest is Politics' (the more internationally-focused UK version) this evening I heard a short discussion of the cultural significance of bagpipes and of musical instruments generally that took me back to those polystyrene plates again. Our stringed instruments are widely seen as beautiful in themselves as well as in sound, and that is true of the instruments of all musical genres, cultures and societies. They are handled with care by musicians and contemplated with a certain awe by most non-instrumentalists; so that when a so-called composer, seeking originality, asks an orchestra to damage their instruments or place it alongside garbage, she or he is on the level of the yahoos in Oliver Cromwell's army who destroyed church organs and shot out the stained glass windows.

I believed my famous (now deceased) colleague Nikki Giovanni (Professor of English) referred to rap often in her poetry courses. I would like to have learned about it from her perspective.

Rap is someone else's culture. I don't diss others' cultures lightly.

This article has been archived and is no longer accepting comments.

November 2, 2025 at 09:29 PM · I answered "no", but it depends on why..

If instruments (or the players!!) are at risk then substitutes must be provided.